Perhaps the ethical responsibility of an individual human now resides in one’s response to the assemblages in which one finds oneself participating’, writes political theorist Jane Bennett in Vibrant Matter.1 Such a de-centring notion of distributed ethical responsibility is especially prescient in light of the energy debates of 2015 which, at the level of politics, were characterised by contrast, radical reversals and unexpected convergences in policy — from the welcome reinstatement of a renewable energies agenda by Malcolm Turnbull, to an eleventh hour global consensus (of sorts) on climate action at COP21 in Paris. In the world of art, institutional and scholarly concern for artistic practices at the forefront of the geo-sciences continues to proliferate. Far from a sudden arrival, the pursuit of rigorous eco-aesthetical research-led practices is nonetheless assuming a heightened level of political resonance as we enter what is now contestably termed the age of the Anthropocene.

While unique in their respective realisation, two exhibitions presented in Sydney in the latter part of 2015 were linked by their shared engagement of the gallery site as an expanded field of energy sources. Both the presentation of Other Currents by Melbourne artist Nicholas Mangan at Artspace and Energies: Haines & Hinterding, a survey of David Haines’ and Joyce Hinterding’s solo and collaborative practices at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), were notable for the extent to which energies functioned as co-producers of the works. In their redirection, transmutation and resonance of energy sources across the divides of the human and non-human, these works encourage a re-thinking of the concept of agency in more distributive terms. Following the polemics of Jane Bennett on vibrant matter and Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory, which emphasises the effective agency of human and non-human actants across a collective, it is possible to suggest that the work of Mangan, Haines and Hinterding embodies an ‘elemental materialism’ that enacts energetic agency as potentiality.2 In this way, their work conceives of art’s relation to social change in a productively open-ended fashion, gesturing towards the possibility of alternative futures and radical ecologies yet to come.

In a recent profile Max Andrews identifies a ‘fascination with the flow and conversion of energy’ as the common thread running through Nicholas Mangan’s distinctive oeuvre of mixed-media installations.3 To date these have variously spanned a fragmentary history of the South Pacific island of Nauru (Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World, 2009–10), a ruinous homage to the obsolete technology of the Walter Burley Griffin Pyrmont Incinerator (Some Kinds of Duration (2011)), and a fictional archaeological excavation staged in Santa Fe, New Mexico (A1 SouthWest Stone (2008)), among other geo-historical investigations into the transformational effects of matter. His solo exhibition at Artspace in 2015 re-presented Progress in Action (2013), the artist’s highly sensorial exploration of the provisional use of coconuts as an alternative biofuel source during the 1989 Bougainville Crisis in PNG, alongside a new commission, Ancient Lights (2015). A two-channel video work that ‘focuses on the sun as a metaphor for the transference of energy and power through history’, the installation was powered via a closed circuit energy system comprising an off-grid supply sourced from solar panels installed on the gallery roof.4 The work thereby marks a new level of complexity and ambition in the artist’s integration of autonomous energy production systems into his unique mode of ‘material storytelling’.5

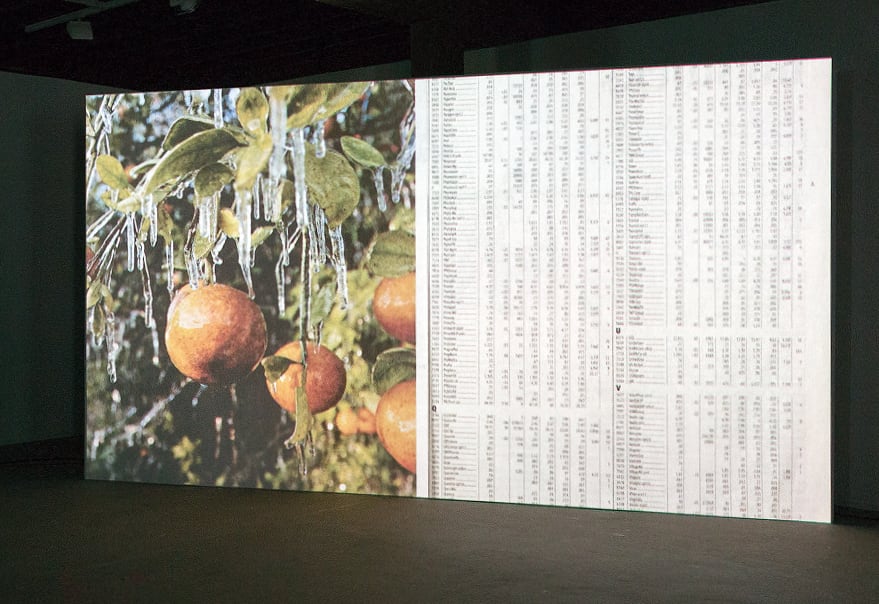

Just as Mangan’s earlier Progress in Action incorporates a coconut oil–powered diesel generator sited in and as part of the installation, Ancient Lights saw the battery apparatuses powering the two video works incorporated into the installation. Housed in an industrial metal cage, their visible placement might have implied an environmental statement or activist gesture on the artist’s part. Yet this literal interpretation overlooks the more critical significance of the presence of the power supply as an actant in an assemblage in which the various component parts functioned collectively, in this instance to provoke a meditation upon the inherently transformational character of solar energy. This dialogical relationship between the off-grid solar supply powering the videos and the ideas explored in the films, both thematically and in the interrelation of energy and light in the cinematic medium itself, was most performatively manifest in the montage video work comprised of footage conveying the cyclical effects of the sun’s activity. Here, the steady clock-like rotation of concentric tree rings was suggestive of nature as both an archive of deep geological time and of climatic events. In another image, overripe citrus fruit hanging amid delicate stalactites of ice-like solar microcosms were juxtaposed against a sheet of newspaper indexing industrial share prices. The unexpected correspondences between these referents point to the entangled nature of modern economies of energy conversion as underpinning, on the one hand, the vital source of life’s sustenance and, on the other, the globalised, borderless commodities market that threatens its sustainability.

Whereas Mangan’s previous projects have largely been extrapolated from the intersecting social, political and environmental narratives attendant to specific sites, Ancient Lights marks a shift toward a more generalised dissection of the teleological rhetoric of progress and futurism underlying renewable energies innovation. The work incorporates footage filmed on a number of locations, including a haze-laden Mexico City, a tree ring research centre in Arizona, and a thermo-solar plant in Spain, where the use of new molten salt heat storage technology promises round-the-clock solar power supply. While the sites were linked by certain material or environmental conditions — hot climates, for instance, with an intensity of exposure to solar energy and its associated effects — a knowledge of the actual sites and their histories was less relevant to this complex cycle of temporally and geographically ambiguous imagery, drawing attention to the paradoxical role of solar as both the energy of the future and of the past. At an aesthetic level, the vast concentric configuration of solar panels around a central vertical tower was redolent of a 1970s Earthwork and, as Mangan himself acknowledges, not unlike ‘something Robert Smithson would make if he was still alive’.6

By contrast, the shorter video work in Ancient Lights captured a spinning Mexican ten-peso coin on a continuous loop in a more austere study of matter in perpetual motion. Considered collectively, the ‘elemental materialism’ at work in Other Currents was discernible at a mechanical, aesthetic and conceptual level. In their preoccupation with flows, conversions and transformations of energy, Mangan’s installations call into question the privileging of human-centred notions of agency that emphasise the intention and will of a human subject. To draw upon the terminology of the late eco-feminist Val Plumwood, the works embody a ‘reconception of nature in agentic terms’, a shift in relations that Plumwood argues is ‘perhaps the most important aspect of moving to an alternative ethical framework’.7 It is in this sense that Mangan’s elemental materialism gestures towards an ‘alternative ethical framework’ in artmaking, assembling contingent spaces wherein the distribution of energies across the human and non-human divide activates potentialities and a thinking beyond the anthropocentric limits of the present.

Closing just a few weeks before Mangan’s exhibition opened in late September, the presentation of the comprehensive survey exhibition, Energies: Haines & Hinterding, at the MCA was in many ways an overdue acknowledgement of the long-time solo and collaborative practices of David Haines and Joyce Hinterding. Yet to describe the staging of Energies as overdue belies the extent to which its atmosphere was anticipatory in a manner that is unusual for a survey show. Reflecting the commitment of curator, Anna Davis, to preserving the deeply spirited engagement with science that motivates the artists’ practices, the responsive force fields that are so distinctive of their work rendered Energies markedly future-orientated in its execution and concerns.

Presented across the MCA’s ground floor galleries, Energies brought together a number of the artists’ iconic energy scavenging installations; including Purple Rain (2004), their seminal piece in Australian video art that reroutes live television signals to trigger the digital simulation of a torrential mountain avalanche, and Hinterding’s elegantly auratic resonant copper wire installation, Aeriology (1995/2015). Collectively, the works exhibited demonstrate Haines and Hinterding’s enduring concern for making manifest the unseen forces — natural, technological, electromagnetic, sonic, occult and otherwise — that animate the everyday beyond the realm of the visible. In addition to representative examples of each artist’s solo practices — from Haines’ work with aroma, electrophotography and hydrogen-alpha telescoped images of the solar choromosphere, to the vibrating objects, topographical loop antennae, listening devices, and tactile conductive graphite drawings of Hinterding — the exhibition also presented a new large-scale commission, Geology (2015). Evolving from the artists’ previous adaptation of 3D gaming technologies into responsive topographies, the real-time 3D environment of Geology utilised motion sensors and spatial 3D audio to immerse the viewer in a multi-levelled speculative geography. In this way, the work reflects what Andrew Murphie has identified as the pair’s ongoing concern to rework existing worlds into ‘more open ecologies of sensation’.8

On one level, this sensitivity to currents of energy, signals and vibrations, and the seductive manner in which Haines and Hinterding bring the viewer into contact with more open-ended ‘ecologies of sensation’ has tended to encourage readings of their work that emphasise a sense of marvel or wonder at nature. Yet it is important to recognise that neither Haines nor Hinterding are ‘eco-artists’ in any conventional sense of the term. Rather, their works operate in the space that might more accurately be termed ‘post-nature’. It is precisely in the activating and remixing of the energetic currents of both technological and natural agents that the pair collapse distinctions between the categories of nature and culture to political effect. Writing about the critical import of a particular strand of elemental construction in the work of a number of Australian women artists, including Joyce Hinterding, Susan Best has suggested that ‘elemental’ is a useful descriptor as it ‘suggests a non-appropriative attitude to nature and substance and, most importantly, an involution or folding back of elemental substance into the way we think about the human’.9 In a beautiful suite of electrostatic photographs or ‘aura portraits’ of plant specimens, Haines’ The Wollemi Kirlians (2014), a ‘non-appropriative attitude to nature’ is present in the surprising revelation of the inherent electrical porosity of life forms. This recognition of the fallacy of inert matter calls into question our own bodily autonomy, encouraging awareness of the inter-agency of the biological, technological and energetic world.

There was a marked sense of timeliness in the close proximity of Other Currents and Energies: Haines & Hinterding in Sydney last year. Yet it is worth remarking by way of conclusion that the intersection of a certain geo-scientific turn in contemporary art with politically urgent energy debates and concern over the age of the Anthropocene also places such practices at risk of instrumentalisation. With this in mind, I have sought to contextualise the energy assemblages of Mangan, Haines and Hinterding in terms of their potential capacity to rework existing hierarchies of agency, the animate and inanimate, into more indeterminate relations. For to insist that artists working at the cross-section of art and the geosciences might offer solutions to the world’s environmental dilemmas is not only misguided but also misses their greater potential import to perform the deep-seated re-compositing of subject/object and nature/culture binaries required to even begin to pose the right questions.

Ella Mudie is a Sydney-based arts writer. She recently completed her PhD at the University of New South Wales.