A small block of tofu makes inroads into an emerging discourse.

Operating out of Tokyo since 1899, the Morinaga Company might be said to manufacture a fairly standard block of soya bean curd. The label on their prime-selling foodstuff — a firm, long-life block of the stuff — reads: ‘This revolutionary package locks out light, oxygen and micro-organisms which lead to early spoilage’. It goes on: ‘Morinaga Tofu always tastes just made — never sour’. It -appears that the consumer likes things fresh.

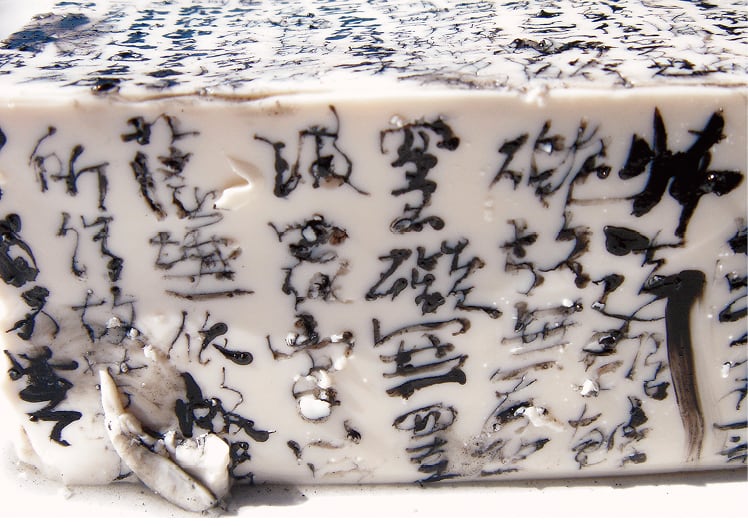

Charwei Tsai’s recent exhibition at the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation (SCAF) in Paddington would horrify Morinaga. In a society obsessed with the sanitary, Tsai’s Water, Earth and Air came complete with a warning sticker boasting unsavoury elements. In Tofu Mantra (2009), the object concerned is Tsai’s canvas; she writes on it along with other materials — mushrooms and leaves, fruit and ice. I’m not sure if Tsai favours using Morinaga tofu, but her canvas certainly appears fresh — at least to begin with, it doesn’t stay Morinaga-standard for long. In the painstaking detail of time-lapse video, Tsai’s perfect block of protein suffers the ravages of time. The words turn yellow, the edges crisp. The centre cannot hold. A fly crawls into the remains just before the structure buckles into nothingness. I worry about the fly — fortunately, it is resurrected upon the play of repeat.

With precursors in 1980s AIDS art and 1990s ephemeral art, bacterial art is a relatively recent mode of practice. Though various works make reference to the virus as metaphor — Félix González-Torres’ candy stacks amongst others — the use of live culture remains an unconventional and somewhat subversive mode of practice. The origin of the movement might be traced as far back as the ‘life as art’ genre of the 1930s and Edward Steichen’s photographs of delphiniums, and through to David Kramer’s bacterial paintings and bio-art of the nineties. Yet the specific field is so narrow that, including Kramer’s painting, bacteria features as a central component in only two major series. The other point of origin is somewhat lesser known, constructed on the borderline of fashion and art by Belgian designer Martin Margiela. He created a series of garments with the intention that they would be exposed to an ongoing process of decay. Working with microbiologists to apply mould, yeast, and other bacterial cultures to cloth, the installation toured Rotterdam, Kyoto, and New York over the course of the three years, from 1997 to 1999. Discourse largely concluded with the incineration of the work — the garments were tossed in a furnace at the request of the atelier — and the use of bacteria in a fashion context has not been repeated. It likewise remains novel in the art world, perhaps because Kramer constitutes such a dominant frame of reference.

Ephemeral art is commonly accepted as an anti-commodification gesture, and the rebellious nature of these works may be seen as a precursor to Tsai’s Water, Earth, Air. It is rather a different idea to let a piece of art destroy itself — to self destruct — than to be destroyed. While González-Torres’ candy stacks are eroded with the underlying expectation that they might be replenished, in Margiela’s travelling showcase the decay is built into the work. Juxtaposition of material and effect creates a dual tension between repulsion and attraction, and the physical manifestation of disease and dying is at odds with a prevailing state of beauty. A direct confrontation with waste and loss is made beautiful, not because the -materials are beautiful in isolation, but because prima facie the aesthetic is beautiful. As a fashion retrospective spanning the decades, the cultural story that is told is also beautiful. The experience of watching this kind of irrevocable bacterial damage occur is akin to the thrill of a celluloid car crash.

The 1980s and 1990s work by González-Torres, Kramer and Margiela share a trait in that they are characterised by the absence of the body of the artist. The groundwork laid in the making of the physical art is invisible, as living culture takes up where the artist’s hand leaves off. The final stage of the development of the work happens independently. Beyond the gore, there is a secondary reason why bacterial art is so confronting: there is a loss of control at play.

Within this small but defined niche, Tsai’s exhibition at SCAF presents a new approach. It is characterised by a heightened sensitivity to states of change, and this resonates beyond the visceral nature of any one work. The screening of multiple video works on seamless repeat suggests a openness to things falling apart — destruction, on loop, is simply another facet of creation. Within the exhibition as a whole, decay is placed in the context of both growth and continuity. It appears as something more than a meditation on mortality. An example of growth, Tsai’s A dedication to the sixth Dalai Lama (1683–1706) (2009) is comprised of miniature bonsai trees. Some of the leaves are inscribed while others are left blank. It takes a moment to realise that the unmarked ones have grown retrospective to the initial act of writing. Another example reveals a continuity — Earth Mantra records Tsai writing on a mirrored surface in the mountains of Taipei. The subtly shifting rhythms of the natural setting are reflected in the flat plane — little changes beyond words, which pass in the manner of time, recorded and uninterrupted.

Perhaps more so than any Buddhist notion of the ephemeral, Tsai’s acceptance of flux and change is the product of a global citizenship. She explains:

I read faster in Chinese, write and speak more easily in English. I live between Paris, Taipei and New York, across three continents. I attend one of the first and most traditional fine art schools of the West, located in France, but I don’t speak French and my work is considered Asian.1

Tsai hints at a fluidity of thinking, which comes from working across both disciplines and continents, and it eschews the myth of the artist-creator in favour of experimentation, process and subjectivity. In the sense of embracing something growing, Tsai is working with a deliberately unpredictable method, consistent with the ephemeral tradition. There is, however, a depth to her inquiry that reaches far beyond the sphere of bacterial art, as a somewhat remote subcategory of ephemera. The notion of ‘working as thinking’ and ‘thinking as working’ comes to mind. Tsai’s tofu might be afflicted by a horde of micro-organisms which lead to early spoilage, but her ideas remain fresh.