‘Images proliferate. Am I wrong in being reminded of the printing of money in a period of wild inflation? Do we know what we are doing? Are we able to evaluate what we have done?’1 — Wright Morris, ‘In Our Image’

In August last year, I made my first ever trip to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. I was there to see Barnett Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimus (1950–51), a large and quiet painting that has — through the writings of Thomas Hess, Clement Greenberg and Jean-Paul Lyotard — been idealised into a cathedral. I imagined it swelling out the far wall of a calm white room with its vibrant, shimmering colour. But when I finally reached the famed abstract expressionist rooms, I encountered a clusterfuck of heavily armed tourists shooting away as if they were on the front lines. Pollock: snap! De Kooning: snap! Rothko: snap, snap, snap! The colours, the space, the energy of pure paint were all erased by the flashbulbs’ glowing afterimage.

Back in Melbourne at the Ron Mueck show recently on at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), photography is permitted as long as you don’t use flash. On my first visit to the show, my friend and I were looking at Man in a Boat (2002) when a security guard approached. ‘You didn’t bring a camera today?’ he asked. We hadn’t. ‘You don’t have a phone with a camera? I could take a picture for you.’ He was surprised when we didn’t want to take -photos because everyone else was.

When I was four years old, I was given my first camera. It had no film in it, but that didn’t stop me from spending hours playing at taking pictures. My familiar backyard became a wholly new and exciting place as soon as I peered at it through the tiny rectangular viewfinder. I remember clearly framing a potted plant in different ways, making the bare winter branches stretch horizontally across the frame, then shifting the camera and letting them skew into the corners. Looking around the NGV, I saw people similarly engaged with the works they were photographing. Like my four-year-old self, it seemed they were seeing in new ways as they looked for things to capture.

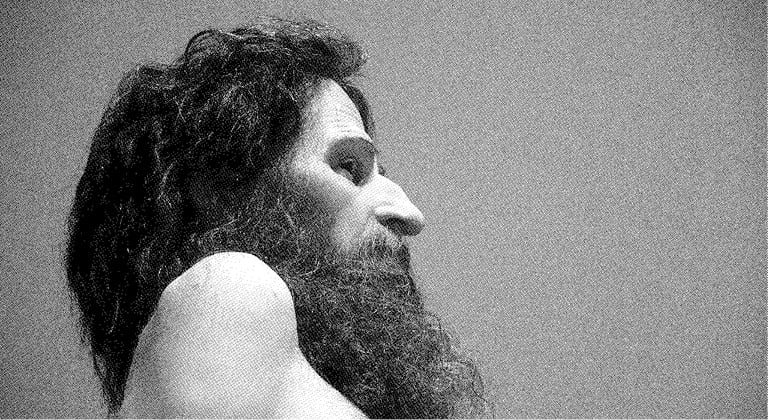

Mueck enjoys the interactions people have with his works when they photograph them, and so he encourages galleries to allow photography in his shows.2 His art is often playful, and taking photographs is another way of playing. It’s true, some people just hold up their phones and click, but browsing through the shots that have been uploaded to Flickr, it seems people are thinking about the pictures they were making. Many of the images were thoughtful and carefully composed. Some of them commented on the nature of spectatorship by including the audience in them. Some played with scale and oppositions of nudity and dress, showing the giant naked Wild Man (2005) beside a suited security guard. The photos made up a visual diary of the exhibition, recording the passing of days.

I decided to have a go at photographing the art myself. At first I felt uncomfortable and exposed holding a camera up to my eye in a gallery, but when I concentrated on looking through the lens, the world of the gallery — the other people, the ambient hum of the building, the spatial relationship between the work and its environs — disappeared and the details came into focus. I fixed on toes, fingers and strands of hair. No longer there just to look, I talked with people about the work and about the photos we were taking — exchanges I rarely have at exhibitions. There was a lack of formality about the exhibition and lightness to the experience that was in keeping with the works themselves. The sensory nature of Mueck’s work was heightened by the possibility of making something of my own and I felt an enlivening sense of communing.

But there’s no escaping the fact that some works need breathing space, and it’s impossible to breathe with a Newman or a Rothko when someone is asking you to step aside so they can take a photo. I know I’m being inconclusive here. I can’t bring you a firm argument for or against the photographing of art in public gallery spaces, but what I can say is that in some exhibitions, like Mueck’s, allowing photography isn’t all that bad. In others — collections of quiet, meditative works — it’s a distraction. Wright Morris was right to ask if we are able to evaluate what we have done. I hope we learn to temper our desire to record our every moment so that we might sometimes have an experience that is moving and ephemeral, and at others, bring out our cameras and play.