In recent months I have responded to two unusual project call-outs to meet with artists I did not know: one occurring in a tiny office at the Abbotsford Convent and another in my bed. As an artist who has sought to create my own encounters with strangers, I was curious to find out why these two Melbourne artists were soliciting moments of face-to-face contact with others. I wanted to know who was taking them up on their offers, and what could be learned from these potentially awkward experiences.

You are invited to make an appointment with The Vorticist. Please visit www.thevorticist.com to arrange a mutually suitable time.

Jason Maling’s The Vorticist is deliberately shrouded in mystery.1 To arrange an appointment, as the project website asserts, is to ‘take a leap of faith’.2 Maling offers a peculiar open invitation to anyone willing to act on curiosity. The website simply states: ‘I need you to understand I can’t promise you wisdom, insight, foresight or even a cup of tea. What I hope for is that for the time we are together we can create a small eddy in the flow of the everyday’.

In June, I made an appointment following a friend’s elusive recommendation: ‘I can’t tell you what happens’ she said, ‘Just go, it’s amazing’.3 The appointment was held in a small office — formerly a nun’s room — at the Abbotsford Convent, where The Vorticist, smartly dressed in a shirt, waistcoat and tie, greeted me in an affable but professional tone. Later, Maling explained that he employs this ‘bedside manner’ as a hairdresser or doctor would, to ease his visitors — and likely himself — through the potential awkwardness of forced intimacy.

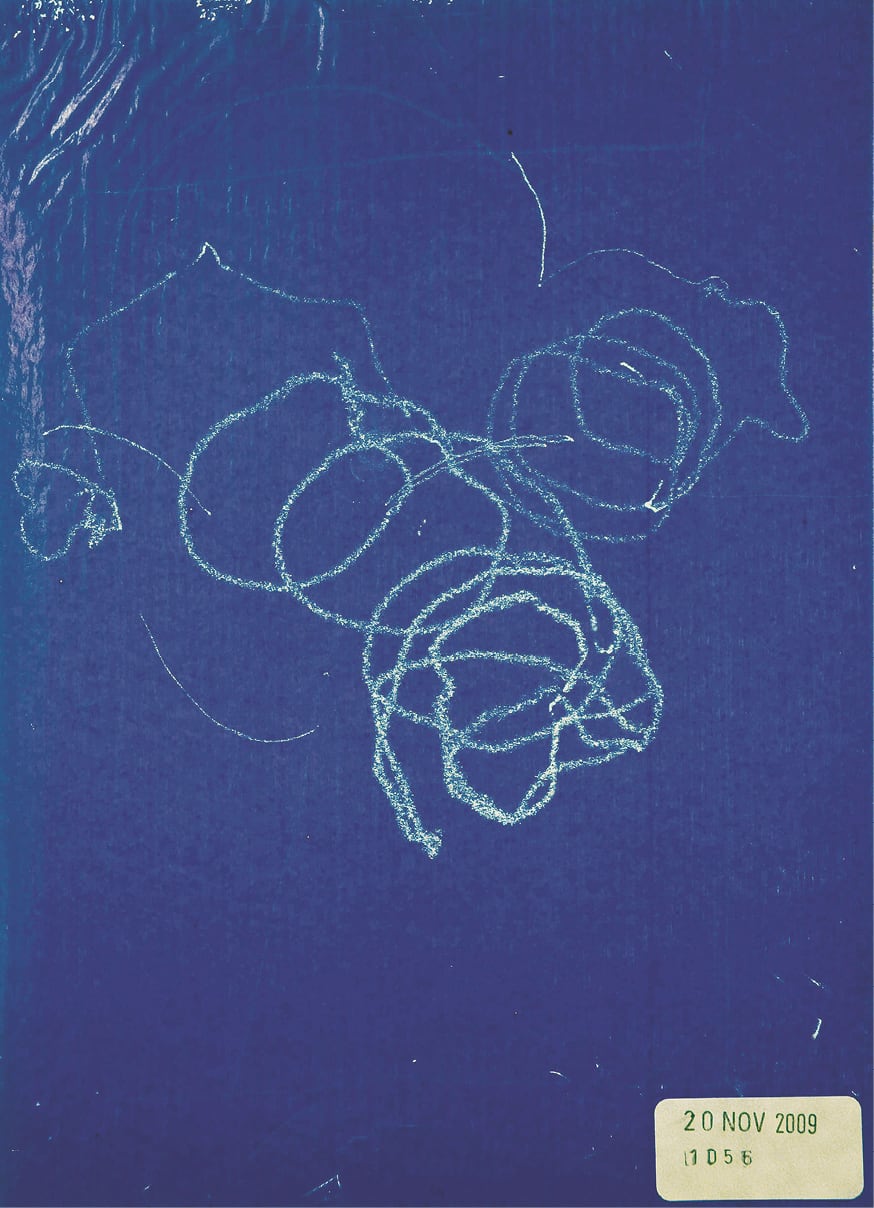

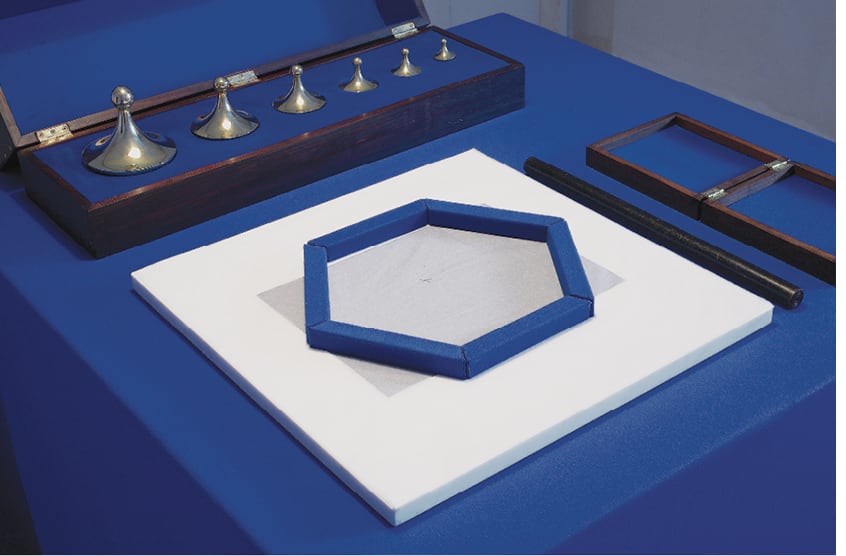

We sit at a table covered in blue billiard table felt on which some curious items are arranged: a whiteboard, an ebony rod, and two wooden boxes. Their significance becomes apparent only later in our meeting, when I am asked to make a drawing on carbon -paper with a selection of spinning tops kept inside a box. I am invited to read into the scribble I make as though it can provide insights like tea leaves at the bottom of a teacup. This drawing and notes from our conversation, I am told, will form the documentation and record of our appointment.

These visual cues seem to suggest that The Vorticist is a professional of some kind, perhaps a psychotherapist or clairvoyant. For Maling, the imagery of the props and participants’ interactions with them are intended to enable ‘a transaction around what you want to believe’.4 He structures The Vorticist so that visitors arrive with no preconceived ideas, finding their own meaning in the experience: ‘I am not interested in making content, in coming up with meaning that is generated by me, it is about finding a structure which causes it to emerge in relation to a variety of elements.’

Maling’s project began in November 2007. Since then, over 300 people have contacted him for an appointment. No predetermined roles or rules, and having no control or understanding of who comes and why, are crucial factors for Maling. Over time, he has found that appointees will often share private details about themselves, many people using the encounter to get things off their chest. This is unsurprising when you consider that it is relatively easy to unburden on a stranger. German sociologist Georg Simmel has written that to be a stranger is ‘a very positive relation; it is a specific form of interaction’.5 A stranger, unconnected to a person’s usual social networks, possesses a valuable quality of objectivity, and for this reason ‘often receives the most surprising openness — confidences which sometimes have the character of a confessional and which would be carefully withheld from a more closely related person’.^6

The Vorticist is a rare opportunity to be given focused attention by a stranger, and as conversation evolves outside of usual social expectations and without any prescribed purpose, it is tempting to place a special significance on what is shared. On reflection, I later regret that I only went to talk about participatory art.

‘I want to sleep in your bed for a night, with you in it.’

Like Maling’s The Vorticist, Charlie Sofo’s B.E.D. project is also an open invitation to any willing participant. On his blog Sofo writes: ‘I’m not sure about this project, really. I’m actually terrified by it. It might be interesting though, so, I’m going to put a call-out: I want to sleep in your bed for a night, with you in it’.7 B.E.D. runs for the duration of 2010. So far, Sofo has accepted eight sleepover invitations, mostly from friends or acquaintances — including a seven-year-old. However, his blog states that ‘everyone is valid’, all that is required, he says, is ‘a leap of faith, I need to trust you and you need to trust me’.

Although B.E.D. appears to be a more simple gesture than The Vorticist, this belies the more difficult and vulnerable nature of the exchange. On an August night, as Sofo and I climb into my bed together, what struck me was there was no bedside manner or structure to assist us through the encounter.8 Sofo did not play a role; he was just himself, slightly nervous and talkative, lying beside me in his boxer shorts.

Side-by-side we face an endless number of preparations and negotiations: ‘You sleep on this side’; ‘Do you want the light out now?’; ‘Are you warm enough?’; ‘Just shove me if I snore’. Without alcohol and lust to fuel our reason for being together, it is more awkward than a bad one-night stand. Lying together in the dark, Sofo mentions that previous B.E.D. participants have sometimes wanted to spoon. I forgo this, however; instead we talk until 3am about our art, past relationships and love.

As with the other B.E.D. encounters, there is no documentation of this sleepover except for a simple diary that Sofo keeps. He explains: ‘There’s no trace other than that we did it — we spent a night together. Everything that has happened, has happened on a personal level, between me and someone else.’9 Preserving the integrity of the act itself, it becomes simply ‘an event that happened, a sentence written on a piece of paper’.

‘Do not give up on your desire’

Criticism has been aimed at relational and socially engaged practices that place undue emphasis on ethical and respectful models for participation and inclusion at the expense of the work’s aesthetic impact. Most notably, critic Claire Bishop has taken issue with the politically correct, activist bent of such projects, observing that ‘aesthetic judgments have been overtaken by ethical criteria’.10

However, Sofo and Maling are not afraid to put their participants through some discomfort or confusion in order to test social conventions. I would argue that they reflect the best kind of socially collaborative art, what Bishop describes as requiring ‘intelligence and imagination and risk and pleasure and generosity, both from the artists and the participants’.11 Such art ‘does not derive from a superegoic injunction to “love thy neighbour”’, but from the position of ‘do not give up on your desire’.12

Their projects are gentle provocations, seeking a shared sense of vulnerability that is dynamic and responsive. They explore the possibilities for exchange in a temporary interaction that would not usually occur. Participants choose to enter this exchange with no promise of rapport, and no guarantee that a good interaction will lead to an ongoing bond, or that a night spent together will result in a follow-up call. These are kind and civil encounters only if everyone involved chooses to be so. They are structured to test the limits of trust and sociability, where meaning must be negotiated and arrived at together.

Speaking about The Vorticist, Maling described one appointee, who quite succinctly captured a sense of the encounters that both Maling and Sofo create:

He explained to me his sense of what was going on. He said, ‘You don’t need me do you? You don’t need me to be here and I don’t think you want anything from me.’ I said, ‘No, not really’, and he said, ‘Well I don’t really need anything from you either and I don’t need to be here either. Well, that creates quite an interesting space doesn’t it, we are both here now so what could this mean?’

Amy Spiers is a Melbourne-based artist, a partner in the creative duo Agents of Proximity, and currently writing a MFA thesis on participatory art.

[^11:] Claire Bishop, interviewed by Jennifer Roche for Community Arts Network: http://www.communityarts.net, accessed 10 August 2010.

[^12:] Ibid.