Kel Glaister (b. Melbourne 1984) is currently in Europe following an Australia Council Residency in Paris at the Cité International in 2010 and is currently on a residency at the 17th International Studio Program of the ACC Galerie Weimar and the City of Weimar. Glaister has been working with sculpture in recent years and this has combined with her obsession with paradox and logic, leading to allegorical, writing-based sculptures. Alicia Frankovich was in Berlin when she interviewed Glaister in Weimar.

—

‘Quality. Is being good enough?’ was a line in your recent 3SQUARE text piece for Conical Inc. in Melbourne, which led me to think of something Thomas Hirschhorn once said in an interview: ‘energy yes, quality no’. This is where I’d like to start with this interview. There is a post-apocalyptic, increasingly less material artist ‘present-ness’ in the way you are working. A witness, a lurcher, an intervener, a cabaret host of sorts, that is how I see your modus-operandi at the moment. Your work seems to have shifted towards somewhat evasive written formats that hover around the art object. What do you think?

I like the way you put that. Like a prowler, a lurcher is someone who hangs around the edges, attempting to go unnoticed but failing (if they succeeded you wouldn’t know they were there at all). And to lurch suggests barely controlled movement. It’s almost a contranym; it can mean to loiter here and to stagger away. I do work in a comparable way. Any given work is a lurching away from previous ideas. So, it will have an intention and aim, but it also comes with more lurching energy than is needed. I tend to overshoot the mark. I guess that relates to your Hirshhorn quote — if you just hit the target, then you have nowhere else to go. But I also loiter around a few recurring obsessions.

I can’t help but relate this to how I’m working right now, and my prevailing obsession with allegory. In answering your question, I couldn’t avoid using metaphor and simile, not to mention the false attribution of human qualities to inanimate objects. With all the desire in the world to speak plainly and directly, you can’t avoid these things. It’s a story problem. Maybe a cabaret-host kind of position is appealing to me because stories are not only an efficient way to transmit information, they are also impossible to avoid.

AF: In your fascinating text accompaniment to your curated show Joke Work at the Cité Internationale in Paris, along with texts for Conical Inc., you ordered a mash-up of quotes from artists, mentors and other disparate sources like The Daily Show, Walter de Maria and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in order to tell your own story. Now, at the International Studio Program of the ACC Galerie, City of Weimar, you claim to be working on a project titled On Dilettantism focusing on ‘transposing Sartre’s OHuis Clos into an allegory of the relationship between artist, audience and artwork’. How do you propose to bring your text into the gallery?

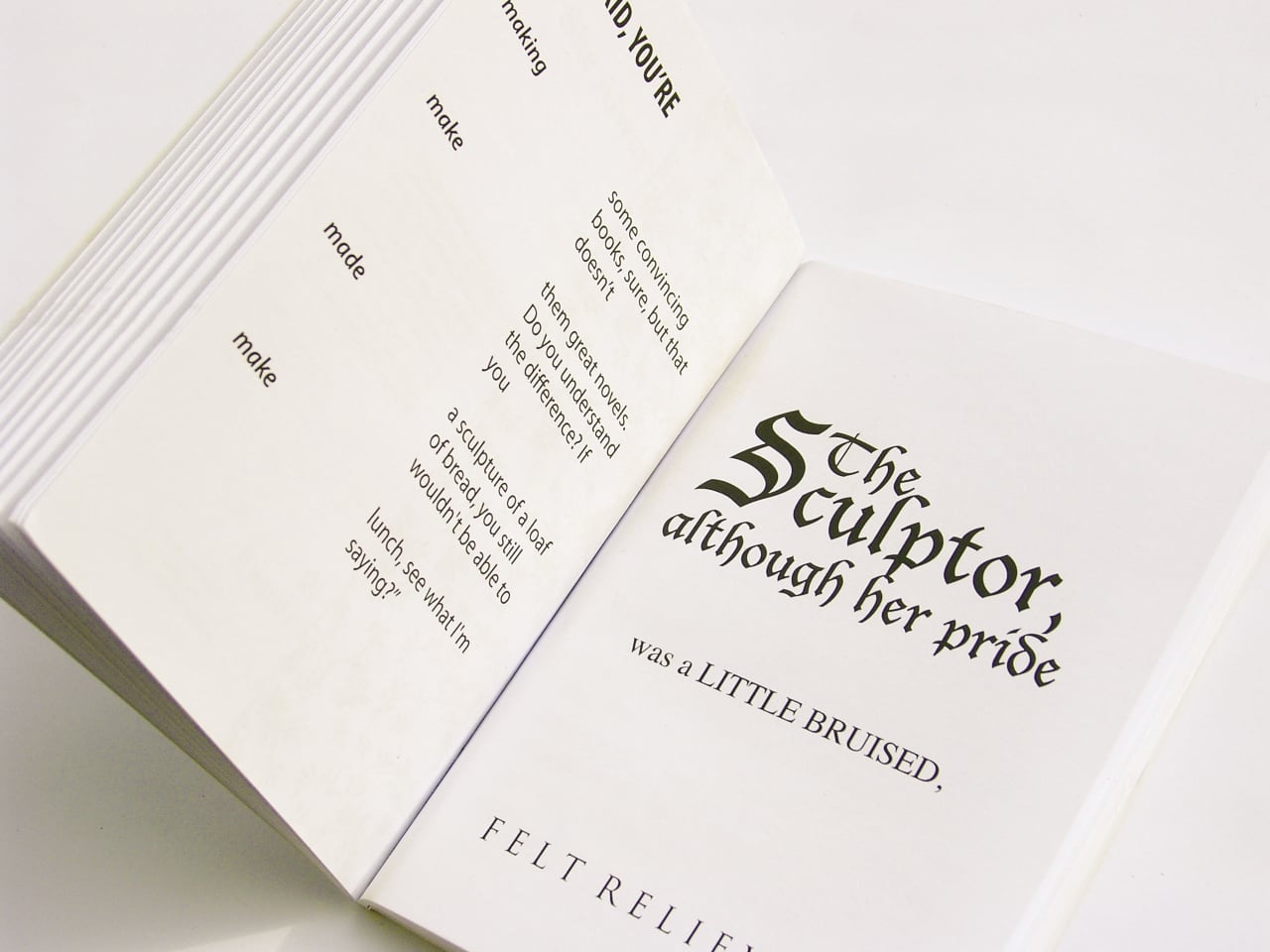

Those earlier essays you mentioned functioned as catalogue essays normally do and they got into the gallery like a flea on the back of the exhibition. Another recent text made its way into the gallery on a different path. For The Aesthetics of Joy: The Infinite International of Poetics held in 2010 at West Space, I made a work called Attractive Futures; an unfinished fable on the Aesthetics of Joy, or the Joy of Aesthetics. I wrote a sculpture of a book. The object is a book, arguably like any other. I say ‘arguably’, because I’d argue that it isn’t. The story is about a sculptor commissioned to make a replica of a library, which she did by writing all the books.

I’m currently working on In Camera, A Closet Drama for the Gallery. A closet drama is a play written not to be performed but to be read, either alone or in small groups. I think they were often derided as dilettantism — something people wrote if they wanted to write a play but didn’t have the rigour or skill to respond to the constraints of actually staging it. It’s in this tenor that I’m writing a play. It’s a fake play that answers to the needs of the gallery not the stage. I’ve taken the scaffold of Sartre’s play and laid an allegory of the rhetorical triangle over it. (I say I laid the allegory over the original, but I suspect it was already there, but that’s another question.) The three characters are each one of the points of the triangle and they speak from inside the work that they constitute; the imaginary space and time of the interaction is allegorically the space of the object and the time of its being read.

I’m working to produce a printed book, which will be the object. Inside will be a play set inside said art object and inside that will be an allegorical personification of the art object. So the writing in these cases gets into the gallery only as constituent parts of an object, which appears to be a book but is actually a sculpture (of a book).

Many contemporary artists are using verbal dialogue and conversations, others are using narration and books. At times, these works bring elements of the stage and notions of performativity into the gallery, whilst others are more cerebral experiences. Take Jill Magid’s immensely complex performative project involving an inside investigation of the Dutch Secret Service (AIVD). One of its exhibited forms was a 2010 softcover book edition called Becoming Tarden, which had been redacted to the Prologue and Epilogue by the AIVD. I am also thinking of Tino Sehgal’s This Situation 2007, in which philosophers and theoreticians quote from anonymous philosophical texts (learned by heart) to start conversations involving museum visitors. Sehgal’s works stem from sociology and economics as well as traditions of art history and philosophy. Janet Cardiff’s audio-walk pieces narrate subjective experiences of urban space, using montages of fact and fiction via personal headphones, as in her Münster Walk for Skulptur Projekte Münster 1997. Is there a strand of contemporary practice or a tradition of art that you are following?

That’s a hard question for me to answer. Largely because, yes, I undoubtedly am, but I’m also right in the middle of this project and it’s hard for me to admit that. You always step into the ring alone. When following a tradition, it’s not only the outcome of one instance in that tradition to the next that is similar, it’s the means of getting there that is repeated. I’d say that I’m not really following a tradition in the vein of the works you mentioned; I’m arriving at it from the other end. Perhaps the point of difference is that I’m lying. I’m making fake conversations and fake narratives. Of course, that opens up a paradox because the logic of narrative, and of making art objects, immediately swells to re-include such attempts into the set. The intention to make a fake narrative will always fail, because it can’t not be a narrative.

The format of a play has been a way to make a model of something that can’t be seen or located. Like an experiment whose results come not from actually observed phenomena, but are inferred from the aftermath. I’m trying to examine how an art work functions, to look at it as a machine. So, for this notional experiment to begin, we’ll have to grant (or at least identify) the starting premise. To wit, there are several fields coming into contact in an artwork: art object-audience-artist, I-you-it, sign-object-interpretant — pick a model. While, in each case, these coincide to some extent with actual people or things, they are also collections of forces that don’t actually exist. We make a story to understand what’s going on and then start believing the story.

What led you astray from ‘object art’ as such?

Writing is building for me. Certain elements or events need to be load-bearing. Words can stack and join like objects. I’m sure a writer would disagree with me, but I’m writing sculptures.

Alicia Frankovich is an artist working in Berlin and is currently participating in the Künstlerhaus Bethanien International Studio Programme 2010–11, as a grantee of Creative New Zealand.