Given that this iteration of documenta has been particularly shadowed by calls for political accountability, manifesting in rigorous critique bordering boycott, the exhibition’s title Learning from Athens could perhaps now, in the almost aftermath, be thoroughly reconsidered: What have we learnt from documenta?1

Unable to make it to Athens, I recently ventured east to Kassel to see documenta 14. Comparatively, the Kassel section of the exhibition has slipped relatively unscathed through the cracks of the institutional critique swarming around the Athens iteration, perhaps affirming the accusations of cultural colonialism at play in Athens. Yet the experience of a densely audience-populated Kassel – lining up for hours to enter the Neue Gallery or shop attendants welcoming us unnecessarily because ‘everyone in Kassel looks forward to documenta returning’ – left me thinking about the necessity of context, and how, in light of a lack of this, can audience development be fostered outside a durational commitment. Or indeed, if it can at all.

Viewing Australian art on an international stage has always been, for me, a kind of eye opener. It often feels like opening a guidebook to your own city and scrolling through the recommendations just to check the information’s validity, rarely pausing to seriously consider alternative opinions to those of your own. This bad-habitual thinking has led me to learn a rapid amount about Australian art while living in Europe. Over the past two years I have effortlessly seen more Australian work that aligns with the kind of institutional practice I believe in than I did in Australia itself prior to my departure. The Australian presentations at documenta 14, selected primarily by Dutch curator Hendrik Folkerts, were introduced to me on similar terms.

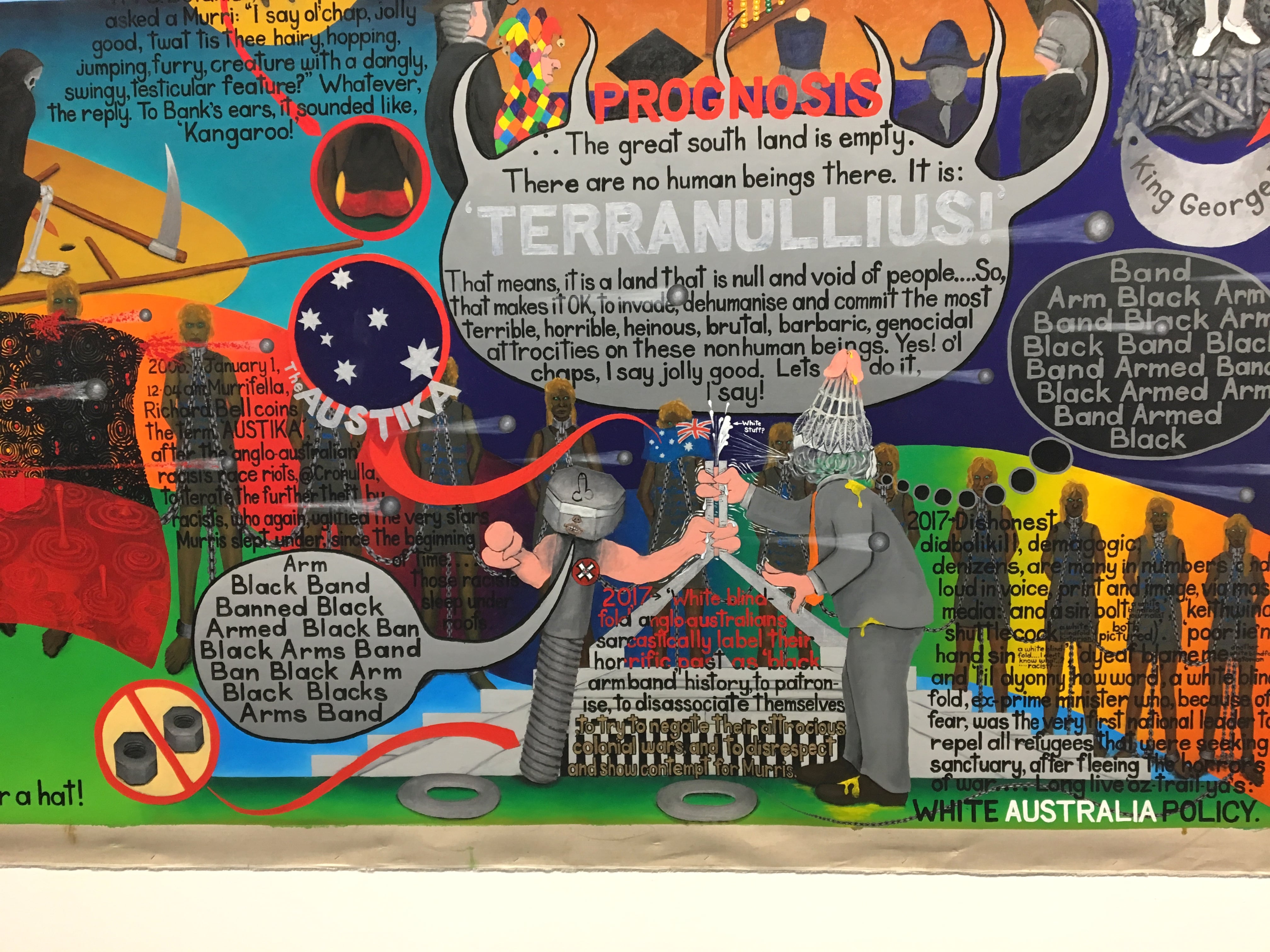

Bonita Ely’s installation at the Palais Bellevue, Interior Decoration: Memento Mori (2013-2017), repurposed and reconfigured a number of largely domestic objects into sculptures which address the militarisation of interior spaces (the home, the mind) in the wake of post-traumatic stress disorder. Gordon Hookey’s contribution MURRILAND! (2017) comprised a large-scale oil painting on unstretched canvas and an even larger-scale mural, which presented a timeline of Queensland through the perspective of the white settler, from its Aboriginal origins through to present-day colonial Australia. Dale Harding’s work at the Naturkundemseum im Ottoneum, Composite Wall Panel: Reckitt’s Blue (2017), was made up of three wall panels with outlines of weaponry, shields, tools, ceremonial objects and traces of the human body – forms all sourced from Harding’s experience of the Carnarvon Gorge in northeastern Australia – painted and screen printed on each front-facing surface.

In light of these works, it is an irony that colonial photographer Thomas Dick has gone largely unmentioned in discussions around Australia at documenta. Dick’s twenty black-and-white photographs from 1910 hang in Museum für Sepulkralkultur alongside John Heath’s identifications of the people in the photos, his 1974 doctoral thesis Birrpai – Beyond the Lens of Thomas Dick and a copy of Marcel Mauss’ book Techniques, Technology and Civilisation. An irony too, that Dick’s work is currently the only of the four contributions to documenta that resides in a national Australian collection.

While looking at Hookey’s work in the Neue Neue Gallery, I overheard a German viewer informing his companion of the context of Hookey’s painting with such matter-of-factness that one could almost believe Hookey’s recount of settler colonial history in Queensland is the accepted history of Australia. This disconnect between the seeming acceptance of Aboriginal historical accounts by the German viewer on the one hand, and the continued historical whitewashing ubiquitous in Australia on the other, speaks directly to the space of curatorial accountability for political works such as these. One can’t help but feel a painting with such pointed structural critique would quite literally be more at home in Australia. Or wonder how Dale Harding’s conceptual use of materials – composite wall paneling made from binding two surfaces to either side of a shared core – might allude to ways in which Aboriginal histories may prevail (or co-exist) in spite of the Reckitt Blue-washing of Australia’s colonial current.2

The displacement of works in Kassel presented a curatorial agenda that has at its heart, I believe, a political practice that could be a way forward; one whereby institutional resources and infrastructures (artworks, funds, employees) can be redirected through the exhibition form itself. The decentralisation of documenta from one location to two produced a possibility for concurrent readings, for seeing how artworks could both operate and be utilised on different terms in different contexts. The presence of Heath’s post-colonial reading exhibited alongside Dick’s photos is metaphor enough for this curatorial attempt for concurrency. Yet in practice, the segregation from structural locations whereby effect could take place seems to leave documenta 14 falling, as art tends to do, into the realm of representation. There was, of course, something significant about showing Dick and Heath together, yet somehow, something neutralising too.

Where might an exercise in curatorial decentralisation leave its audience? Is there something to be said for the hoard of locals visiting documenta in Kassel and the hoard of tourists visiting it in Athens? Why does it seem to sit sourly on my tongue that a German can walk past this painting and assume it to be our known and accepted history, when the same cannot be said for most Australians? And what does this say of the implications and responsibilities of curatorial practice in global context? It left me wondering what the implication would be of exhibiting these four artists together in Australia under the guise of a national image? The insistent exclamation mark at the end of Hookey’s title – asserting that it’s the Murri peoples land, not the Queen’s land! – would surely not seem as unnecessary as it does to the eye of the aforementioned German viewer.

Isabelle Sully works as an artist, curator and writer. She is currently undertaking a Master’s in Art Praxis at the Dutch Art Institute, the Netherlands.