To walk through the main roads, small alleys, places or neighbourhoods that a mass protest has touched is to negotiate tilted grounds. What used to be the flatness of the everyday — double-deckers’ squeaky engines, fences and traffic lights managing anonymous bodies, endless lines of advertisements — now acquires a different shape.

Protest sites of the current pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong1 have been marked sonically and visually by such slogans as, ‘If we burn, you burn with us’ in English, and in Cantonese, ‘I would rather be ash flying than dust floating’2 and ‘I would rather cry out to die than stay silent to live’,3 in addition to the ones directly asserting the goals of the movement, like ‘Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times’ and ‘Five Demands, Not One Less’. Likened to war zones, these protest sites evoke the imminence of destruction, as much as the need for creative disorganisation from the bottom up, for good.

1.

Stephanie Sin has recently applied to overseas graduate programmes in heritage and the ancient Chinese art of paper. To leave or not to leave has been a question on her mind.

‘On the streets, an argument between strangers would suddenly break out. I had to find a place for myself to think, away from the tension,’ Sin recalled.4 She committed herself to a six-week residency in the southern city of Tainan in Taiwan, but as the movement grew bigger and more intense, she struggled with the decision to leave. ‘I thought seriously of turning it down. But I spoke to another artist who said everyone’s role in the movement could be different.’ Sin decided to go, but insisted on coming back to Hong Kong twice during the residency to join the protests.

In Tainan, she researched the experience of elders who had been through the Japanese occupation of Taiwan in World War II. She started to wonder about her paternal grandmother, how she might have had similar experiences in Hong Kong. ‘I would call my dad from Tainan at night and have long conversations with him about how women were in the war. I know so little, and there’s no such research in Hong Kong.’ She was fascinated by the degree of detail of the historical research, and was particularly drawn to doing historical research herself in the midst of the current movement. ‘I was in Admiralty in a demonstration one day. Suddenly, police came from many directions. They fired tear gas randomly, so the air became white and smoky very quickly. I stood there, frozen.’ In hindsight, Sin realised she had become less eager to be on the frontline. ‘I am a person of action, but perhaps it’s age, I find out I am not the kind of person to be on the frontline this time because I may think too much to need others’ rescue. I don’t want to become a burden for others.’5 She reflected upon how different she was in the Umbrella Movement,6 being in the occupied areas almost every day, making barely any progress in her art.

Her recent paintings show traces of her transformation. HongKongers: Something of a Revelation (2019) is a set of two paintings.7 One shows human figures wearing black outfits, recognisable as protestors in the movement.8 The other depicts figures wearing green outfits, the anti-riot police officers. Both groups of figures have featureless faces, but their postures and bodily gestures are expressive. Each person in each group seems to be absorbed in their own world. As a whole, however, each group is at peace, in a moment of contemplative pause from action. The composition of one mirrors the other. Placed side by side, the artist equalises them on an aesthetic plane. This aesthetic equality frees both groups from the frequently circulated images in the media; their violent confrontations are suspended. The artist makes space for the imagination of what lies between and beyond the groups, and for empathy with each individual as being a whole person, not just a statistic in the movement.

I once asked Sin: ‘Is art resistance?’ At first she said ‘no’ without hesitation. And then she elaborated: ‘Art making is art making, but in Hong Kong making art is already very anti-society.’ In the context of Hong Kong, making art non- commercially and against established institutional parameters could be a form of dissent. Essentially, one could also say, it is by insisting on thinking differently, responding to instances where society’s vision fails, that one enables a different economy of attention.

2.

Mix-media artist Sui-Fong Yim presented her first solo exhibition, ‘A Room of Resistance’, in the autumn of 2019, roughly four months into the movement.9 One of the works was an installation entitled Against Step. It consisted of a solo dance video projected onto two translucent screens hanging in the air. The male dancing body at times convulses and stretches, but never leaps, as if to bind himself to the ground. In front of the projection were eight television sets, each showing a video of a person on the street in an absorptive moment; for example, a little girl breakdancing, a silvered-haired man rolling his shoulders back in a stretching exercise. Yim was fascinated by how they seemed to be elsewhere — free from worries, free to be in their own worlds. Each person could be a model for everyday resistance.

Yim has been video-recording similar encounters since she returned to Hong Kong in the middle of the Umbrella Movement in 2014, after working in Beijing for three years.

A feeling of unease first prompted her to move to Beijing, and similarly, nudged her back to Hong Kong.

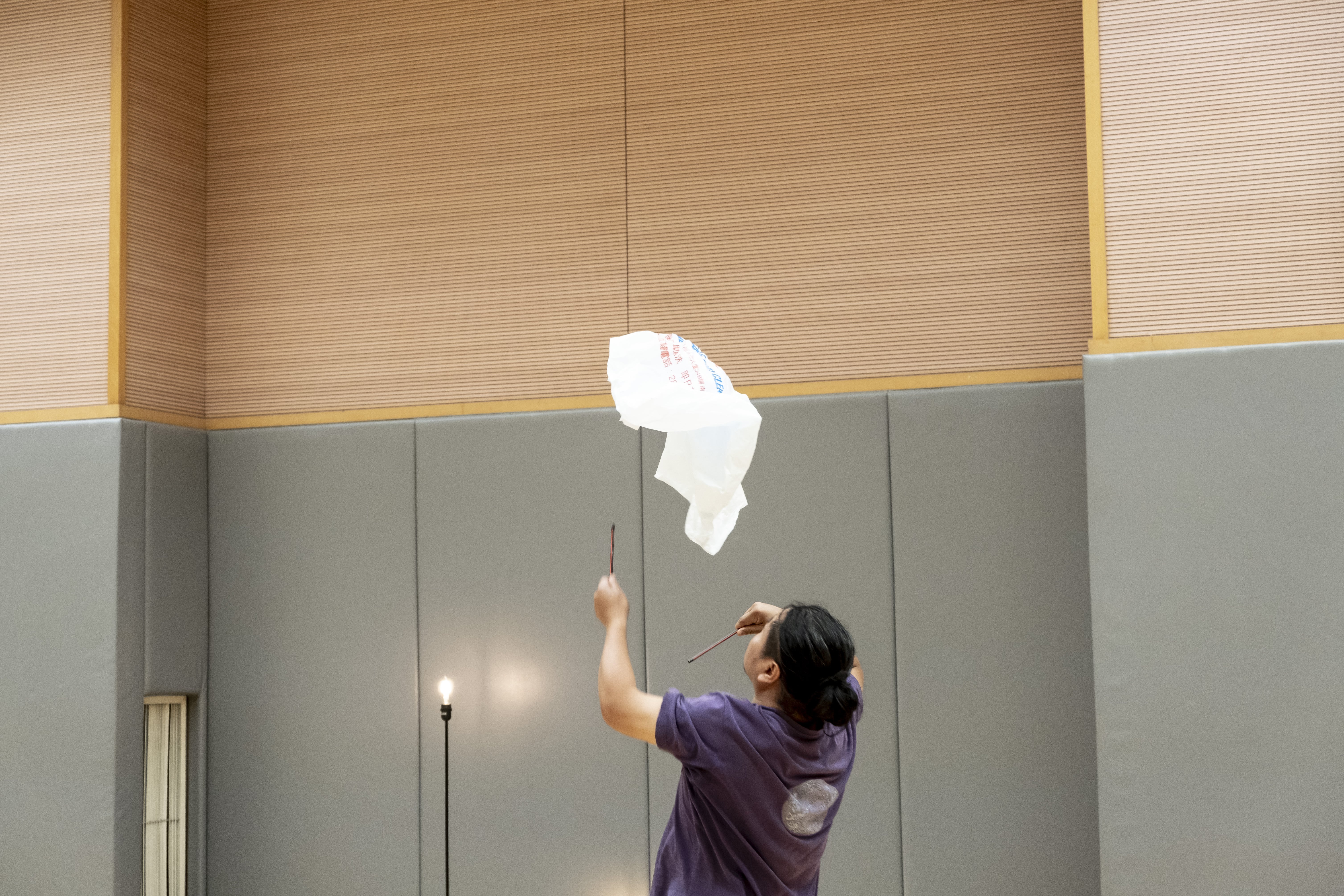

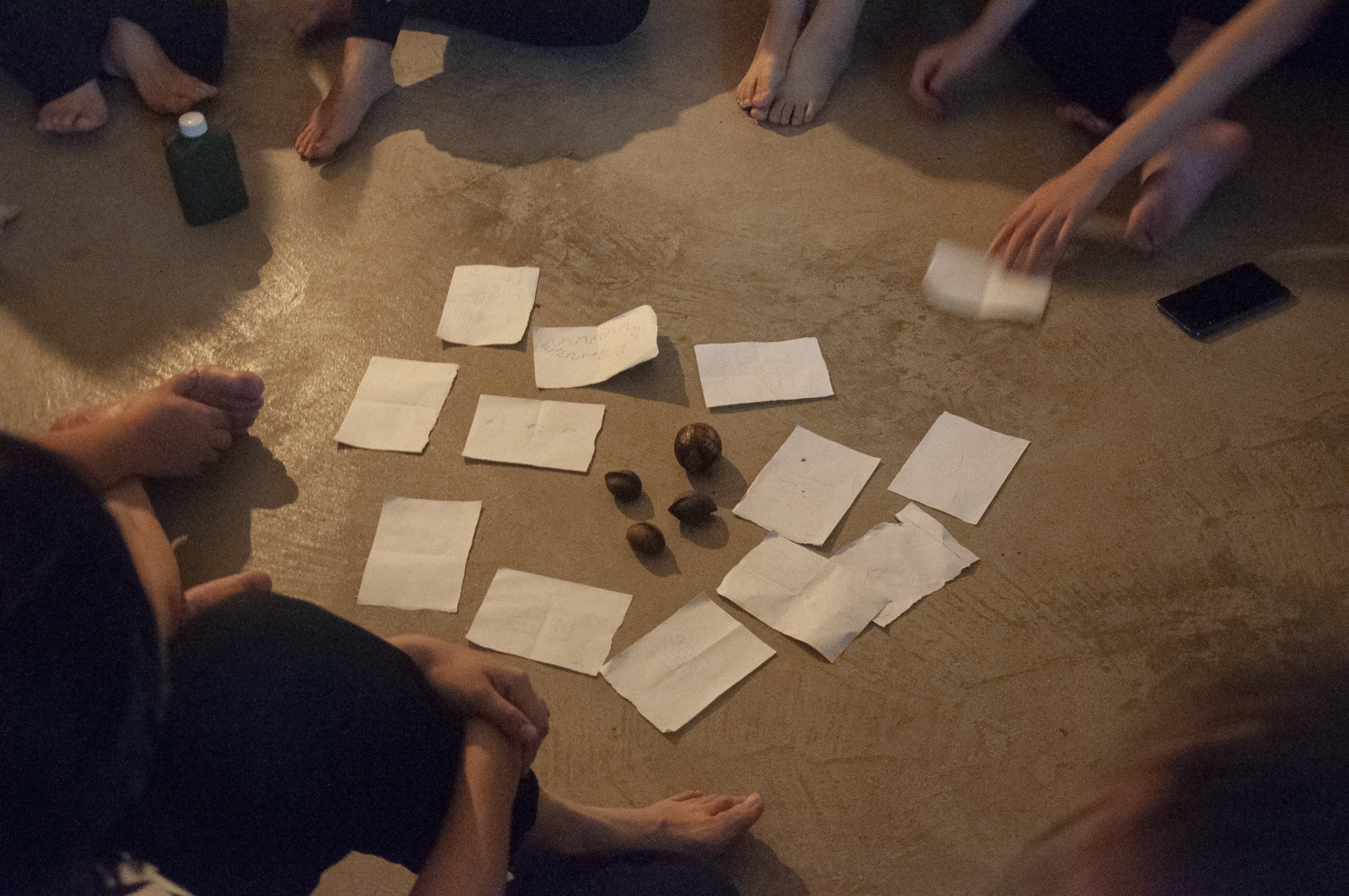

Yim founded Assembly of Disquiet in early 2019. By conducting open calls, she recruited ‘contributors’10 to join workshops in which they communicated by using bodily gestures and objects instead of words, including whistling and falling in between walking. For one activity, the group visited a remote island of Hong Kong for a one-night stay, taking sound walks to learn about the place and collectively creating songs, turning their experiences into rhythms and sounds by knocking onto objects, for instance, and stepping and dancing. The workshops become a way for everyone to encounter ‘difficulties’. For example, a dancer who disliked counting beats expressed this by drawing. ‘Every time and for everyone, what’s disquieting is different. We were not clear about what would happen. I wasn’t very clear myself. But it’s amazing we could share what it’s like living in Hong Kong at this time,’ Yim said.

Yim found out she was pregnant in June 2019. Her studio and office in the Rooftop Institute11 is located in a building on a main road of the district of Wanchai where all mass demonstrations would pass. Yim felt frustrated that she could not join the demonstrations as much as she wanted. Through Assembly of Disquiet, she channelled her frustration into creating collective experiences. Yim is empathetic without losing touch with her needs. ‘I’ve always thought of others first, but I started to feel my feelings. And it’s only then I can start creating again. I must care for my own heart first to have sensitivity,’ she said.12

3.

In Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education, Nel Noddings identifies one core sentiment of ethical behaviour: not only feeling for the other, but also feeling with the best self of one for the other. ‘When we commit ourselves to obey the “I must” even at its weakest and most fleeting, we are under the guidance of this ideal. It is not just any picture. Rather, it is our best picture of ourselves caring and being cared for.’13 She emphasises that this is not abstract, but a concrete situation where one is engrossed in the other.

For both Stephanie Sin and Suifong Yim, attending to what societal standards deem to be less urgent is to attend to what they are best at as artists. They demonstrate their capacity to accept and make the most of an agency that is distributed, dissipated and partial, but one that is historically responsive — aware of being not entirely in control of changing circumstances, while trusting that art contributes to who we are and who we will become, for ourselves and each other.

Yang Yeung is a writer of art and an independent curator in Hong Kong.