APOCRYPHILIA was at The Northern Centre For Contemporary Art, Darwin, until 30 March 2019.

This interview took place on Larrakia Country. We acknowledge the Larrakia People as the Traditional Owners of the Darwin region and pay our respects to Larrakia Elders past, present and becoming.

Beth Caird: Could you tell me about your upbringing in the Pentecostal Church?

Matthew van Roden: I was born into it. My parents’ stories are theirs’ to tell, but they were wild-childs who found each other in a beautiful, disastrous, beautiful way and hit the road. Then they started a family. And then they found the Jesus freaks in Sydney.

They got off the gear and got straight into the really, really intense Pentecostal religion of the 1970s. Charismatic Christianity was really soaring then. Christian rock was just starting out, things were really taking off. There was a lot of momentum that bought in a lot of people worldwide. My parents were part of that movement, straight into the full-on life of the church, which was simultaneously really thrilling and disastrous in many different ways. They had a really difficult time because both my sisters have disabilities that require 24-hour 7-days-a-week care, and it was a situation that was never really embraced by their community at the time. It was almost suspicious. In some ways you are in and in some you are out, things are challenging and intense and you have to strive for your faith and your position within the community. I was just born into that situation. Church was twice on Sunday, midweek meetings and prayer meetings on a Friday.

We left Sydney when I was four and moved to Darwin. We found a congregation here and they were super intense and it was a lot of speaking in tongues and miracle healings, visions of Christ, prophecies, and all of the miracles. Lots of whooping and Amens and hallelujahs.

I can tell you infinite stories, of crazy manifestations and things that I saw with my own eyes, that I touched with my own hands and I really believed. I'm not saying that they're true or were real in any way other than my impression of them, or that they even actually physically happened. They were, however, real to me at the time. Foregrounding that is really important to my practice because I understand that sense of an utterly unequivocal belief.

I come from another perspective now, looking back at all that with another set of beliefs and ideas. So, it works - it cuts both ways. I think it's a discomforting sensation for people who are still on the inside of that because I'm on the outside saying, ‘hey I felt like you and now I don’t.’ But also, it makes me think about my current standpoint and what I think now and having, hopefully, a healthy skepticism at all times, that how things are now can be completely and utterly different. I think that it's rational no matter which camp I'm standing in. I find that really exciting. But where I come back to, that notion of the aesthetics of my Pentecostal upbringing is that I bring that energy and I bring that application, even with my skepticism to my every endeavor. And I bring that to my practice, I bring that to my reading, to all the things that I'm doing. It's in that sense that I often say I'm throwing out the baby of monotheism but I've kept the bathwater. I find that a really rich approach to things. Maybe I didn't always but I think that's something that's come through these bodies of work, at least something I’m trying to figure out.

Beth: Your work references orientating towards something and reminded me of Sara Ahmed's Queer Phenomenology and relationships with objects that orientate us towards queerness.If a person’s sitting in a room at a writing desk with a pen and a notepad and maybe a table lamp, we understand that person's relationship to writing within that scene. The other example she uses is our body’s orientation towards the chair and towards the table when we're at a dinner table but it's actually about our orientation towards the person across the table from us. Drawing orientation towards the person is perhaps drawing queer lines — or how our bodies might know how to be around an open fire. I was also thinking about Claudia Rankine writing about complex proximity in her poem of the same title where she writes, ‘How can I say this, so I can stay in this car with you?’ and she's talking about so many complex things happening in the metaphor of the car. We know in a car how to speak and how to use voice. And it's like this orientation towards a car or a table or a writing desk, to actually towards each other...

Matthew: I love that notion of being side by side. That intimacy of speaking forward is really lovely.

Beth: That sounded like she was trying to locate a known way of changing orientation. In your practice, how did you develop that knowing of how to orientate your body, which is the text and your reading practice, and your body?

Matthew: Oh, this comes back to how I approach reading. When I made that clean break with my religious self and my religious life, my religious practices, there was for me a total void. It was a no-man's land and I went from the platform of the church to the podium of the gay club. Performed in drag for a while. There was this textual void as well; what was going to fill that?

I'm understanding my orientation to certain texts as not just proximal, as in other to me, but, rather, as somehow constitutive of me. I'm not saying that it's internal. I'm saying that in a Foucauldian sense, my internal is just the inside of the outside. The other side of the ribbon that's all tied up in knots, right? In terms of a proximity it's actually constitutive. My orientation in that sense is ... well I can't say projection because that's too psychological but it’s all enmeshed. Textile, text, it's all about the warp and the weave, right? The language, the light, what you can see, the words you can use to describe it. It's all there as a fundamental part of the makeup.

What I wanted to achieve through this main body of work [APOCRYPHILIA] is to give that experience, the bigness of that weaving, that inter-meshing of body and text to the audience. For me that is the revelatory moment of the text, realising its utter significance as something that feels really larger than life. It gives an opportunity to place the viewers smack bang in the middle of that sensation, where all of a sudden you have this strange relationship with the body and a body of text. What is that?

After my Bible days, I began reading Nietzsche, then I hit Heidegger pretty hard, perhaps devoutly. I was, like, here's someone whose idea is really to up-turn the whole world in terms of how we understand our role in ‘worlding’, that sense of the tools, the equipment and then that being a realm of existence. Up until the beginning of this study, Heidegger just made things work and helped me to understand that it's not from the outside in it's from the inside out toward the world. That was nice because the biblical thing is all about how we look at the world from the God's-eye-view, looking all the way through the universe and eventually towards and into us.

Then I just hit Foucault like a motherfucker, I hit Foucault at the beginning of this period of study. There's language-being that creates discursive fields and there's the non-discursive which is the light-being or the visibilities and somehow there's a dynamic of power bouncing in between these things. And we're in the middle of all of that, realising a radical externality and a radical outside. Then somehow, we're all folded up and it makes our sense of self. The text is in me. All of these texts are in me. It's really actually a part of who I am, Hallelujah!

Beth: In the past, you've mentioned that you go outside, which is the inside, of the outside, of the inside in your work.

Matthew: Yeah totally, my perspective … just because I can make the comparison means it's an inside-out perspective, in a way. You can never really be extrapolated. It’s a statement on the notion of proximity.

I think, rather than looking at binaries I'm really looking at doubles. So, it's like the inside of the outside or the left of the right. It’s not the left or the right. They are expressions of something more nuanced and complex.

Even Canon and Apocrypha are a double in a way because those texts jumped from one side to the other throughout the history of the Christian scriptures. They change location, from canon to Apocrypha and back again over time. Who's in charge? So, it's more a sense of the double rather than the binary yes.

Beth: Yes, and doubling allows for everything to still be there too.

Matthew: It's kind of what Esben Esther Pirelli Benestad was saying about polarities as opposed to polarisation. There's a sense of wholeness in polarities, positions which are part of the same object, whereas polarisation is a Mars vs. Venus situation.

Beth: A Christian notion is to privilege honouring the body as this vessel for God that can be sacrosanct or holy; asking for a giving-off of autonomy to the church for a larger whole. I wondered if your work was seeking out that in-between space but also that meshing of objectivity and thingness to try not to privilege the agency of the body and, like, not privileging desire?

Matthew: Yes, maybe I could bring into this the notion of Canon and Apocrypha. Again, I'm really reading that as not a binary. I'm looking at canonisation as a process, 'apocryphisation' as a process. But in the same way that the term queer can be used in that noun adjective verbal really dynamic way. I want to take the apocryphal space and sort of verb it. Then there is this notion within the church that this is the body and vis-à-vis the body of Christ here and there's this canonisation of the way things should be, and the text works in the same way and the text affirms the body and the body affirms the text. This thing is like a building of an edifice, the community, the position, the structure of the hierarchy, the mode, the practices, and how they constrain the body. The space outside of that is kind of apocryphal space, right?

It's the spurious, the illegitimate, the strange, it's the porous, it’s the fucking cyborg. It's infinitely creative and if you, instead of being cast out, if you leap over your own head in an ecstatic, Nietzschean movement, then you become the ‘Apocryphiser’; you’re empowered, you're creative, an infinitely mutable form. I find that notion an analogue of queer and queering. So, I think they kind of speak to each other, but I guess that's from the structure of my own upbringing and experience.

Beth: Your exhibition made me think about vagueness as, like, a strategy for survival and living. I was wondering if the works are deliberately vague at points?

Matthew: Oh, yes, there is definitely obfuscation and opaqueness. That's definitely through the wax, the materiality of the wax. The work in The World Becomes Flesh and Apocryphillia was made by getting those tones in a really specific way, matching tones to different parts of my body, finding colours in my own body. In my mouth on my palms of my hands and my elbows and, like, I'm boiling the wax I'm trying to colour match them. When the wax dries it lightens ever so slightly and then it goes a little bit opaque, so it’s an opaque attempt at finding colours in my own flesh. It really is my own body of text.

At the same time the language is really opaque and obfuscated and you get this sense of a clear reading and then perhaps you‘re not really sure what's happening. There is a confused relationship between the body and the body of text or a body as body or as text.

Opacity is absolutely there as a strategy. That's not to say that I'm feeling really clear about things. On the other side, it's that opaque screen. There's definitely a continuing wrestling.

Beth: Yes, and obfuscating is different from being silent and from a refusal to answer. Being vague can be such a strong tactic that you deliberately use. Being unsure, aloof or unreliable; I'm kind of obsessed with unreliability as a mode at the moment, or being unsubstantiated or illegitimate as ways towards resistance?

Matthew: Absolutely. And so yes, that is being apocryphal. It’s taking up all of those things and saying, ‘oh well okay, according to what measure? According to what standard?’ I'll make and exist in the borderlands and on the periphery of those standards. I'm also on the borderlands of using the language and the tropes of that religious experience too, and saying, ‘hey, shit, like, it's inside of me so it's mine to use.’

Beth: Can you talk about what an apocryphal approach to reading is?

Matthew: Maybe I can bring some Foucault back into the conversation. In terms of statements. He's not looking at the content of the statement as the truth of it. And if we look at the novel then what, like, the enterprise of queer studies has done – as with gender studies, as with feminist studies – is to kind of go back in and deconstruct the text itself and query what the text can be or reveals. ‘Oh look ... here's the suspicion that we had about the sexuality of the author, or here's this character and they're actually sort of gender bending but only when they're in the kitchen.’ And that's really going to an inside space of the text. The apocryphal approach would be ... .re-reading texts with a deep subjectivity. I'm not reading this text the same way that you're reading this text. It’s a reading that pushes the text into a different space.

And that changes the reading. I think that might be more apocryphal. Like, what information then becomes important? What other information can we pull out of a text or even what other what other suspicion can you pull out of yourself by engaging with it? Or, like, what's an outcome that it produces in another field entirely? Maybe that could define the apocryphal approach? Like really, where did you get this story? Like, where's your authoritative sources? What about the lifestyle of the person who gave you the information? What about the fact that you were really high when you got it? There is so much richness in not being suspicious of the text but allowing more of those doors to be open than would be closed because of suspicions about legitimate and illegitimate readings. In some way, reading is always an appropriation, apocryphal reading takes this as a productive process.

Beth: In thinking about this exhibition I was reflecting on Perniola's The Sex Appeal of The Inorganic and how he doesn't believe in objects. He only believes in things. I remember you saying that reading is practice. I'm interested in your relationship to meditative reading and spiritual texts having an authority in a language that allows you to go into a meditative or performative headspace. Into a friction between object-ness and thing-ness. Your artwork in this exhibition seems to show that the performativity of the text allowed you to transcend into that space of thing-ness. In Christian rhetoric, the body is this vessel that is distinctly object-orientated as the vessel for the Word of God, the in-filling of the spirit. And your body is not yours and it's owned by a higher power. And with the Bible, you've spoken to this beautiful duality ... as well of the Bible being a spiritual text to be consumed, it also has the thing-ness of a big book, materially. Could you expand on the materiality and duality of your body as a text-object?

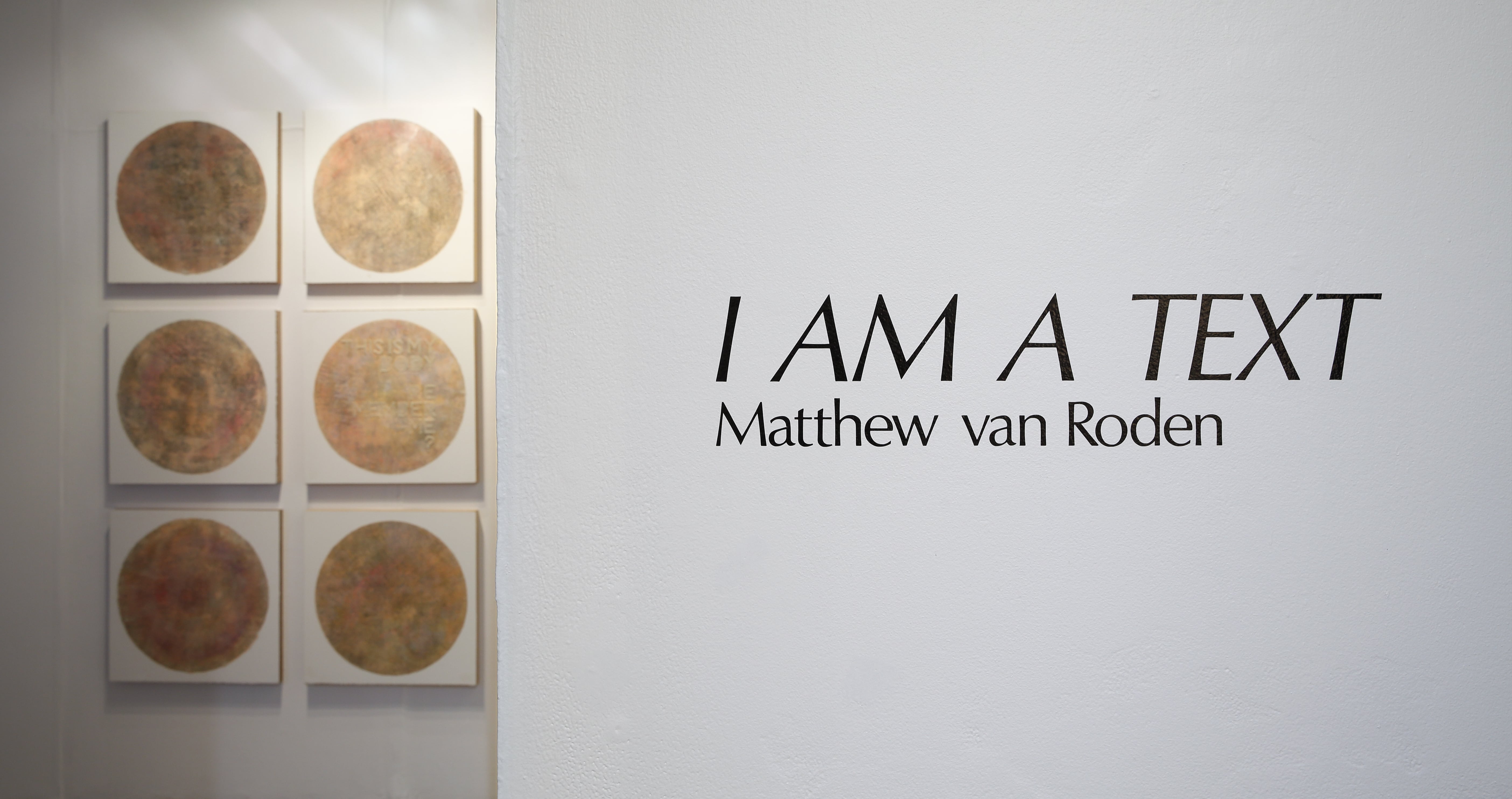

Matthew: When I started these lines of investigation, I was doing printmaking with wax plates. In the work, I AM A TEXT those circles, which I call Eucharistic blisters, are wax plates that go through the printing press. I was interested in the printing press as the global proliferator of texts. In fact, I'm not really interested in printmaking at all, really, but I am interested in the machinery. So, there was something nice that developed, almost a fetish for the printing press. It was like we were dancing it was just this pressing of the flesh. It was like, it actually felt quite sensual I think, maybe it still does, there's something really beautiful about the process.

There was also a kind of poetry in it because the printing press was made to proliferate text. So here is this proliferation of the flesh in a way. And I’m kind of fucking it up because they're all mono prints so there was no proliferation at all. It’s subverting the machine in a way. It’s through the press that I started playing with my body as a text-object. Pressing the flesh like a text?

Through video I was using the flesh in a different way. I rely really heavily on green screen and I love it. It's funny because you've got this green material that actually disappears space. It creates kind of in-betweenness so it's really lovely. But then, like, the body is always disappearing or melting into itself or into a background body and it's hard to distinguish where, I guess, where one begins and one ends. Is it the same thing? Is it a different body?

With the wax, there was a lot of play on control and editing as I went. Heaps of what was there was because the fans I had were on and wax went everywhere. There's a lot of control and I guess intention in the process. It was an endurance piece. It might seem like it falls into a droppy mess but there's lot of control and intention in that and nothing is discarded. I really am attracted to artists for whom nothing is discarded. There can be excess but not waste. Certainly, my approach is that I really want excess but I don't want superfluidity.

Matthew van Roden is a Darwin based queer artist working with wax, text and flesh. Beth Caird is an artist, writer and curator and previous sub-editor of un Magazine volumes 9.1 & 9.2.