I’m looking through a tiny window at the silvery surface of the sea roughly 10,000 metres below. I don’t know where I am, or which ocean this is. After five straight days of lectures, workshops, panels, exhibitions and performances at Berlin’s transmediale festival, I can barely concentrate on the text in front of me, an essay called ‘The Beach (a Fantasy)’ by Michael Taussig, part of a battered collection that’s followed me lately on slower trips, by boat, across the Baltic and North Seas. In it, Taussig writes of how the sea and ships have largely disappeared from our direct experience of the world, despite a deeply enmeshed dependence on ‘the ocean and its histories through the commodities brought in the hulls of ships’. With reference to Allan Sekula’s incredible documentary work on seaborne freight, Fish Story (1989-95), Taussig notes that our reliance on the sea must only increase in today’s global free market economy, and yet ‘nothing is more invisible’.1

These thoughts were echoed in the first keynote lecture for transmediale, Politics of Forgetfulness, in which Françoise Vergès called for ‘a decolonial geography of the sea’, arguing that theorists like Silvia Federici have overlooked the ocean – the ultimate in-between or negative space – as a site of enclosures, dispossession, extraction and colonisation, and that forgetting the sea (as substance) means ‘forgetting where we stand’. Vergès made the point that for many Indigenous communities, land and sea don’t function as such clearly demarcated categories. Earlier in the week I’d seen a Karrabing Film Collective work at the nearby ifa Gallery as part of Riots: Slow Cancellation of the Future, a show curated by Natasha Ginwala. In their video The Jealous One (2017), an envious sea monster, that therrawin or durlg, lays questions of desire and (dis)possession over and across the supposedly discrete bodies of ‘the land, the man [and] the settler state’.2 Visibility and erasure ebb and flow here in lines that certainly do not stop at the seashore, revealing how invisibility, as one presenter at the workshop Surface Value, Landscape Prediction put it, is always contingent and structural.

For Vergès, the sea is both surface and ancient, unthinkable depth, the kind of intermingling soup that Haraway demands we make cloudy through disturbance. Invoking Derek Walcott’s poem ‘The Sea is History’, Vergès points towards an expansive forensic approach to that complex subterranean that I looked for, but only found pockets of, throughout the behemoth that is transmediale. All this talk of appearances and lightly concealed structural violence is down to this year’s festival theme, ‘face value’, which rather literally shapes the form and content of its offerings, with the sea being more of a quietly recurring guest, surfacing every now and again.

transmediale takes place over several days each year at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), an institution occupying the discreetly glamorous former Congress Hall in Berlin’s Tiergarten, built in the 1950s for hosting international encounters. HKW’s program is reliably forward thinking, and this festival of media, culture and arts has a reputation for engaging critically with the horizons, and increasingly the politics, of digital culture. Its artistic director Kristoffer Gansing frames it as an ‘intersectional meeting point’ between art, activism, philosophy and science, with the 2018 iteration directly confronting how politics unfold in new social landscapes marked by neoliberal economics of value extraction and the digital financialisation of everything. Just as today’s dominant platforms deal in momentary, surface-level engagements, the first event, Tell It Like It Is: transmediale 2018 Opening Rally (Really) was a polyvocal soundbite marathon, a line-up of participants given a few minutes each to pitch a cause that they would go on to complicate within the body of the festival. Amongst impassioned and playful calls for Truth, little narratives, ‘molecular solidarity’, and the precariat of Europe, we were treated to a rousing poem by Alex Foti: ‘O peasant rise from your slumber / and riot in multitudinous number!’

In the main exhibition, Territories of Complicity, the sea was back with a vengeance, though less as matter than medium. Dubbed ‘experimental’ since a space for talks, workshops and screenings was part of its architecture, the show in fact felt a little clunky. Most viewers were squeezing in a short visit between other events, taking in whichever of the eight cramped shipping-container rooms on offer were least crowded. The exhibition’s departure point was the free port, a key node in global circulatory systems that reveals how easily data, goods, money and people elide what appear to be regulated state borders on the back of transnational corporate infrastructures, supply chains and banking networks, creating corridors and zones of exception where accelerated relations between ‘the organization of space, accumulation of wealth, and racialized control of bodies’3 determine new (and often frightening) economic, legal and socio-political realities.

The material then is quite dense, and the videos, environments and documents on display did benefit from the artist talks and performative presentations playing out in the event space. Notable among the works was Lisa Rave’s Europium (2014), a dreamy video tracing multiple curious back stories to everyday substances of money and screens via europium, a naturally phosphorescent rare earth mineral used in both, and haunted here by its modes of extraction and histories that entangle the animism of traditional Tabu shell currency in colonial Papua New Guinea. Structured like a nautilus shell (the logo of the company, Nautilus Minerals, currently attempting to launch the first-ever deep seabed mining operation in the Bismarck Sea),4 the film circles around Rave’s abstracted access points to those stories – her desktop screen in Germany, archival footage, and mechanical deep-sea mining toys in a drab corporate office.

Speaking alongside Rave was Femke Herregraven, whose work, Sprawling Swamps (2015-18), proposes a set of fictional infrastructures located on swamps, ice and unstable shorelines. Encountered as an interactive virtual space and a row of folders with labels like ‘BOOTLEG TRIBUNAL FOR NONHUMANS / GREENLAND / MELTING GLACIER’, Herregraven’s materially dynamic territories undermine the land/water binary but also question legal frameworks and the limits of financial geographies, suggesting ‘exhaustion, regression, gossip, and empathy’ as new forms of value. Sharing her investigations on catastrophe bonds and the submarine internet cable planned for melting Arctic permafrost to aid high-speed trading, Herregraven outlined her use of ‘truths’ to create other narratives, pointing out the fiction already operational in imagining you might make money from whether or not a hurricane happens.

In the container room opposite, Forensic Oceanography (Lorenzo Pezzani & Charles Heller) showed research from this branch of the emerging forensic architecture field, who use the technologies of border policing to instead track the violence of those borders, countering ‘the regime of (in)visibility imposed by surveillance’.5 Amongst their output is the Alarm Phone project enabling vessels in trouble to be identified, and a ‘drift map’ of what was known as the Left-To-Die boat, made up of data gathered on the winds and currents that ‘bear witness’ to such an event.

Shifting from frontiers to free flows, Demystification Committee’s Offshore Investigation Vehicle (2017) reproduces the workings and bureaucracies of an offshore corporate structure in order to study it. Having established a series of linked companies across the UK and the Seychelles, described as a little working model, the artists showcased here their Spring/Summer 2018 range of tackily branded beachwear along with assorted paperwork and procedural documents. After recounting a tale of 1970s corruption, coco de mer and sorcery in the murky world of offshore finance, the artists hosted an accounting-performance, being a shareholders meeting to distribute the first meagre dividends. The boredom of watching fifty shareholders queuing to sign one by one for their 50c cheque in a little ziplock bag, this on day five of the epic program, was perhaps not unintentional.

Back in the festival proper, University of the Phoenix (Max Haiven & Cassie Thornton) were offering a Workshop with the Dead for Radical Economic Transformation. Appropriating the face rather than backend of a neoliberal corporate structure, the University is another ongoing project that takes a surprising approach to activism, in this case ‘raising the dead and talking with ghosts in order to bring down global capitalism’.6 Divided into two parts, the workshop walked with finesse what is often a perilous line between cynicism and sincerity. In the first, the artists delivered a slide show of their pedagogic activities in the context of racialised finance capitalism. These involve a range of experimental methodologies, since ‘the dead speak to us in symbols and metaphors’, including working with dance to address debt, and seeking guidance from an invasive plant, ‘the Immortal Stranger’, as teacher and symbol of resurgent, caring resistance. During a walking tour of San Francisco’s Bay Area, seeds of this plant were thrown into the headquarters of a ‘vulture fund’ tied to local (mostly black) foreclosures and exploitative loans in Puerto Rico, to grow strong and do infrastructural damage.

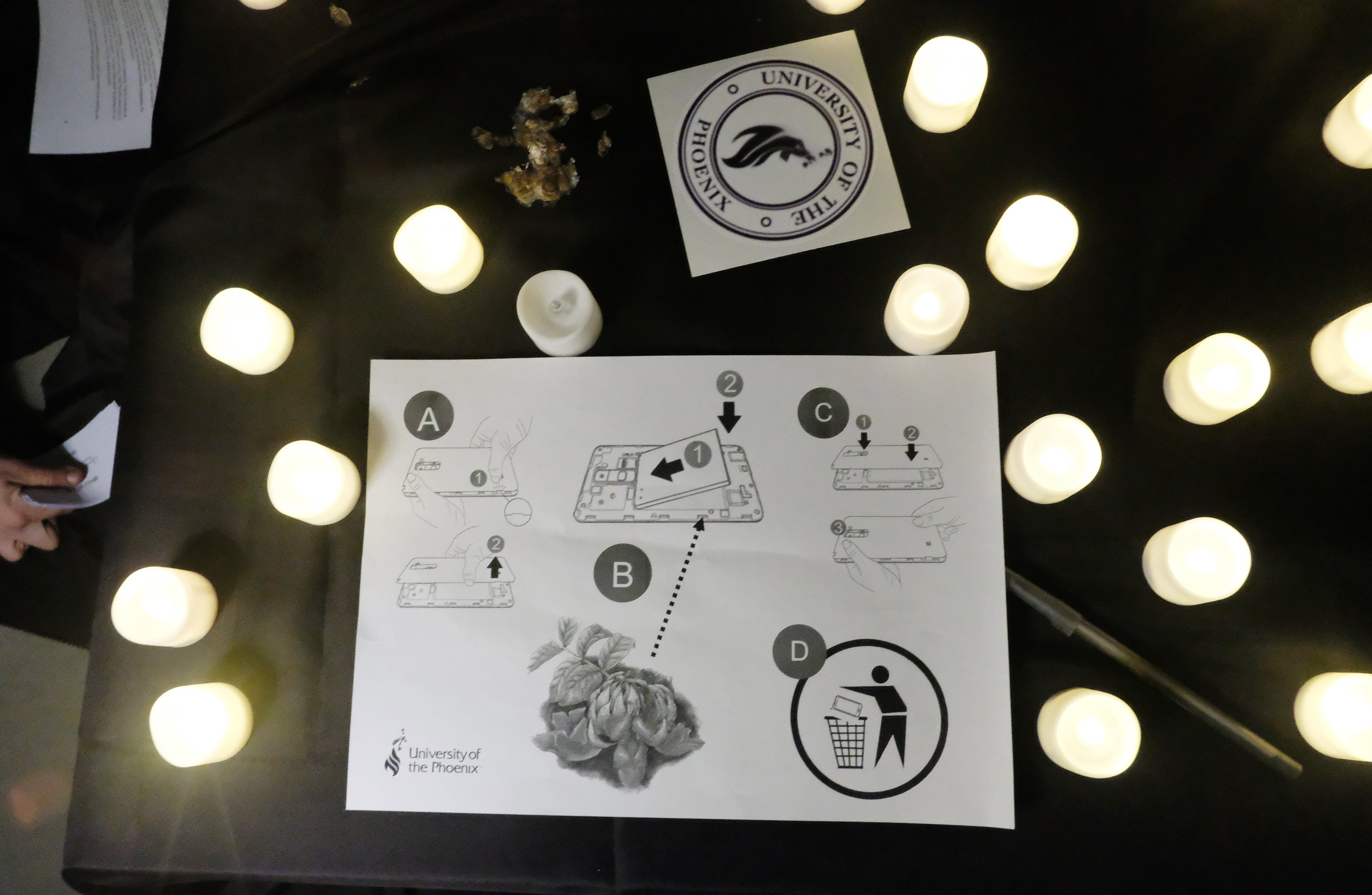

In Berlin we dutifully handed over our phones for part II of the session, first sealing one Immortal Stranger seed onto the phone’s surface to accompany it to its end-of-life e-waste facility destiny. For this next phase we spread out on the floor to follow a series of guided exercises designed to return autonomy from networked systems of control, then conversed sitting back-to-back with a stranger about work and desire. The final task was to pose a fundamental question to the dead, channelled through another participant. My question, about how to collectively build things of substance when people are so atomised, was unexpectedly answered by Mark Fisher, whose ghost certainly haunted many edges of the festival. Receiving back our phones, which had meanwhile been mystically transformed into dual-function devices able to tap into the dark network of the dead, we were sent back out into the world cleansed, bonded, bewildered and enlivened.

Workshop with the Dead for Radical Economic Transformation is a project concerned more with devising collective strategies and rituals for transforming the invisible structures that dominate our daily lives, than with mapping all the inside/out positions in relation to those structures. Stepping beyond critique to formulate a response, with imagination and sensitivity, to what lies beneath, is a tension that appears often in these discursive settings, something the workshop’s very special visitational guest, the eminent Ursula K. Le Guin, knew all about.

I’m looking at a second text in my pile of badly-filed references, Le Guin’s ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’, as I hover here in nowhere, and am thinking about the sea as a container, and what it means to have lost sight of that. In a time characterised by the post-truth weariness of knowing just how rotten everything is under all those shiny surfaces, practicing political therapy across the divides of life/death and reality/fiction might be a way to make new stories that can hold things ‘in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us’.7

Tessa Zettel is an artist and writer collaborating with others on various forms of making, researching and sharing. She is part of undisciplined groups Collective Disaster, Weathering and The Librarium. Recent projects have been hosted at HIAP Suomenlinna (Helsinki), Akademie Schloss Solitude (Stuttgart) and MUCA Roma (Mexico City).