Between Schadenfreude and Saudade

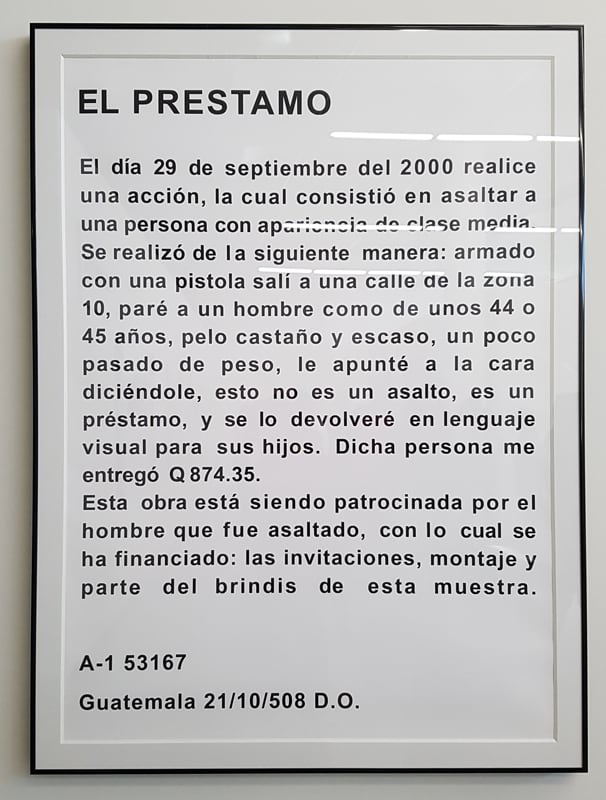

On 29 September 2000, the late Aníbal López, also known by his Guatemalan ID number A-1 53167, undertook a ‘mugging action’ for which he robbed a person of middle-class appearance at gunpoint. He used the stolen 874.35 quetzales (equivalent at the time to US$115) to fund an exhibition at Contexto, a commercial gallery in Guatemala City, recasting the subject of his violence as a philanthropist. Describing the incident in a framed text, El Préstamo (The Loan) (2000), López notes that wine served at the opening was purchased with the stolen money, rendering gallery patrons’ accomplices to the crime. The moral ambiguity of López’s action prompted curator Rosina Cazali to suggest that his description of a crime stimulates in the reader a perverse desire for it to have occurred (cited in Es-calon, 2014). I’d suggest a kind of schadenfreude, the German word for taking pleasure in another’s misfortune.

El Préstamo stood at the entrance to López’s mini-retrospective, featured in the 33rd Bienal de São Paulo (SP33), 7 September – 9 December 2018. According to the Bienal’s curator, Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro (n.d.):

López also applied his razor-sharp critical eye to the art world and its rituals, questioning how value is determined, and how art relates to the broader economy.

To art critic Ben Davis (2018), El Préstamo reveals ‘just how dangerously deep you have to cut to startle the art audience’.

SP33 occurred during a time of intense political upheaval in Brazil. The impeachment of popularly elected president Dilma Roussef of the Workers Party in 2016 set the scene for the then-minor conservative politician Jair Bolsonaro to rise as a populist right-wing presidential candidate. Often dubbed the ‘Trump of the Tropics’ for his nationalist stance and divisive rhetoric, Bolsonaro is better understood as a product of Brazil’s military, representing the interests of its former dictatorship (1964 – 1985). Many fear that his recent ascent to the Presidency marks the return of that regime.

The build-up to the October election saw significant protests in Brazil’s major cities. The #EleNão (Not Him) campaign brought millions into the streets protesting Bolsonaro’s stance on Black people, Indigenous people, women and gender non-conforming people, propelled by anguish and anger over the assassination of queer Black councillor Marielle Franco in Rio de Janeiro in March of 2018. Earlier this year, investigators disclosed that employees close to Bolsonaro’s family have been linked to her killing (Ramalho, 2019).

Further fueling the mood of disaffection, a fire in Rio de Janeiro’s Museo Nacional on 2 September 2018 destroyed much of its collection, just days before the Bienal opened. It remains an enormous tragedy that many argue could have been prevented if the museum were properly funded and managed. Events that followed were tainted with a sense of this loss; what Brazilians might call saudade.

Over several attempts to review this Bienal, I found myself swinging between poles of schadenfreude and saudade. It irked me to discuss the staging, production and consumption of contemporary art as I came to grips with ingrained divisions of race and class and intense social inequalities in Brazil, all the while as an authoritarian government was ushered in.

Affective Affinities

The title of SP33, ‘Affective Affinities’, combined ideas from Goethe’s novel Elective Affinities (1809) – which proposed a theory of social relations premised on a scientific understanding of chemical reactions – and Brazilian art critic Mário Pedrosa’s thesis, ‘On the Affective Nature of Form in the Work of Art’ (1949), which discussed the productive relationship between the artist’s intentions and the viewer’s sensibilities across a diversity of forms. Thus, according to the Bienal’s press material, ‘Affective Affinities’ was not a theme but rather a description of Pérez-Barreiro’s ‘operating system’ which prioritised experience over discourse. Resisting the predominance of ‘curatorialism’ that has accompanied the world-wide flourishing of biennials ‘in which the curatorial concept is greater than the sum of its (artistic) parts’, Pérez-Barreiro distributed curatorial power across seven ‘artist-curators’: Alejandro Cesarco (Uruguay/EUA, 1975), Antonio Ballester Moreno (Spain, 1977), Claudia Fontes (Argentina, 1964), Mamma Andersson (Sweden, 1962), Sofia Borges (Brazil, 1984), Waltercio Caldas (Brazil, 1946) and Wura-Natasha Ogunji (USA/Nigeria, 1970). Representing a range of ‘backgrounds, generations and art practices’, they were invited to curate their own work into a series of group exhibitions. These were supplemented with twelve individual projects actually curated by Pérez-Barreiro, including posthumous exhibitions by the aforementioned Aníbal López (Guatemala, 1964–2014,) alongside two of his lesser known Latin American contemporaries, Feliciano Centurión (Paraguay/Argentina, 1962–1996) and Lucia Nogueira (Brazil/UK, 1950–1998). New commissions were awarded to Alejandro Corujeira (Argentina, 1961), Bruno Moreschi (Brazil, 1982), Denise Mi-lan (Brazil, 1954), Luiza Crosman (Brazil, 1987), Maria Laet (Brazil, 1982), Nelson Felix (Brazil, 1954), Siron Franco (Brazil, 1950), Tamar Guimarães (Brazil, 1967) and Vânia Mignone (Brazil, 1967).

In contrast to recent editions, the world’s second oldest Bienal under Pérez-Barreiro’s stewardship was a scaled-down affair, allowing newcomers to appreciate the expanse of the Oscar Niemeyer-designed Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion situated in São Paulo’s sprawling Ibirapuera Park. Pérez-Barreiro avoided artists whose practices are overtly activist, journalistic or socially-engaged, although he insisted his artist-curators had total artistic freedom. The result was a self-reflexive, but surprisingly conventional, exhibition that seemed disengaged with events outside. Appreciating its capacity for ‘deceleration’ in an era of mass distractions, Davis (2018) described SP33 as of ‘deliberately and provocatively small claims’. Given the circumstances in which it unfolded and the significant platform the Bienal reserves to make a statement, others lamented it as a missed opportunity (Dushá, 2018).

While I empathise with Pérez-Barreiro’s frustration with the theoretical cladding that regularly accompanies contemporary art exhibitions, I was challenged by his program of ‘deactiviating discursivity’. To my mind, an appreciation of contemporary art comes from its intermingling of aesthetics, theory and politics and its appeal to capital and financial power. While art remains an elite discourse, for me its interest lies rarely in the subjective experience of the objet d’art, but rather with the drama of the major art event.

Crisis of representation

Sofia Borges’ exhibition, The Infinite History of Things or the End of the Tragedy of One, unfolded as a labyrinthine ‘Surrealistic Salon’ drawing on several years of research conducted into ‘mythologies concerning the egg’. It was ‘a tragedy from the point of view of the impossibility of a solution for the relation between matter and meaning’ (Borges cited in Bienal de São Paulo, 2018).

The entrance to her exhibition was marked by a large black and white photograph of Selk’nam people indigenous to the Tierra de Fuego archipelago, taken by the Austrian priest and ethnographer Martín Gusinde in 1923, next to the words writ large: ANTES TUDO ERA UM (BEFORE EVERYTHING WAS A). Gusinde’s photographs, recently published in a book The Lost Tribes of Tierra del Fuego (2015), document the last male initiation ceremony, Hain, ostensibly staged for his camera, before the group succumbed to introduced diseases and genocidal pogroms by European invaders. The figures and ceremonial characters portrayed in Gusinde’s images were echoed in Borges’ performances for camera, employing masks and body paint and making reference to archaic mythologies.

Ceiling-to-floor velvet drapes organised Borges’ maze, in which one came across sculptures from the likes of Sarah Lucas and the late Brazilian icon Tunga (1952–2016), often in an assemblage with artworks sourced from Rio de Janeiro’s Museu do Imaginário Inconsciente de Nise da Silveira. The col-lection includes the artists Adelina Gomes (1916–1984) and Carlos Pertuis (1910–1977) alongside others who remain anonymous, exemplifying Borges’ program of ‘de-authorship’, as works in combination multiply their potential readings. Large text paintings punctuate the visual field with oblique declarations. Two texts hung side-by-side might read:

Tudo ao redor era um ovo / e tudo objeto salvia a verdade

(Everything around was an egg / and every object saps the truth)

or

tudo ao e tudo

redor objeto

era savia

um a ovo verdade

(everything is everything

around object

it was sap

one to the true egg)

The exhibition was confidently staged as a passage from dark to light, and evidently Borges was able to mobilise significant resources to bring it to fruition. Its centrepiece — a ‘mirror’— were twin abstract assemblages by Leda Catunda hung back-to-back, Eldorado (2018) and Eldorado II (2018). Their titles reference the mythical city of gold that Spanish conquistadors sought in Mexico at the expense of Indigenous lifeworlds. If these were the exhibition’s heart, then Tal Isaac Hadad’s Recital for masseur (2018) were its lungs, or rather the chorus to Borges’ tragedy. Each day a small group of singers gathered in a central enclave to ‘practice’, warbling wordless drones, while being manipulated by a masseuse, their modulating tones accenting the acoustics of the pavilion’s voluminous space.

According Borges’ artist statement: ‘The founding state of language is tragic: we can not [sic] under-stand, understanding is impossible’. I find it difficult to ascertain if Borges’s proclamations are inten-tionally absurd. Regardless, they are evidence of the crisis of meaning she pursues. I’m amused to read Borges’ ‘dissertation-installation’ (Duschá, 2018) described by one arts patron as an ‘under-graduate thesis’ on photography in Bruno Moreschi’s commissioned ‘unofficial’ archive of the Bienal. Somewhat more problematic, Davis (2018) observes, is that Borges ‘seems to flirt with using Indigenous people as a figure of the universal unconscious, a queasy gesture that someone should have questioned’. It is notable that Selk’nam is a dying language, with its last fluent speakers having passed away in the 1980s (Shepard Jr, 2015). Certainly, Borges’ evocation of Indigenous people seems insensitive to ongoing colonial appropriation (and antrópofagia) of their land and culture in Brazil and elsewhere. This tension is exacerbated by the coincidental fire at Rio de Janeiro’s Museo Nacional in which irreplaceable Indigenous objects and recordings of languages no longer spoken were destroyed (Greshko, 2018). Bound together as multiple tragedies of neglect, The Infinite History of Things ... stressed the startling under-representation of Indigenous artists in the Bienal.

Wura-Natasha Ogunji warrants special attention as the only Black artist selected by Pérez-Barreiro, a remarkable oversight in a country shaped by African slaves and who are integral to its mestizo make up. Ogunji’s exhibition, always, never (sempre, nunca), focused on Black and diaspora artists who foreground site, architecture and the body in relation to their personal histories.

Ogunji made use of the pavilion’s large windows, which in contrast to Borges’s curtained hide-and-seek gave a sense of diffusion between the exhibition space and gardens, signaling to the world beyond. In this airy ambience, Nicole Vlado’s sculptures staged a double take. Mounted on transparent perspex plinths, her plaster casts of the floor below emphasised their surface fissures and negative space filled in with polished brass; a poetic gesture towards the ‘intimacy of cleaning’ (Vlado cited in the Bienal poster series). Likewise, Youmna Chlala drew attention to the exhibition’s architectural de-tails. Her Loveseats (2018) circluded the pavilion’s structural columns with forms reminiscent of sea creatures, inviting patrons to sit close to the building’s ‘spines’ to experience their bodies in the artwork.

Ogunji’s stitched drawings were hung from the ceiling to be viewed from both sides, emphasising her section’s thematic traversals across architecture, space and time, front and back, inside and out, surface and structure, past and premonition. During SP33’s opening days, Ogunji organised a performance, Days of Being Free (2018), a ‘choreography of freedom and leisure’ involving twenty women dressed in black who, with the assistance of the audience, were draped in colourful wax-print fabrics. Com-memorated as a billboard-sized photograph, the group portrait was hung above wide external ramps connecting the pavilion with the surrounding gardens, their daily use echoing its choreography. Viewed from the exhibition windows, the building’s vectors, glass reflections and the passage of daylight reframed and pulled focus towards the performance documentation, unwilling to let it remain a production still.

Arguably Oguni’s most striking inclusion was a series of ‘appearances’ by artist Lhola Amira, a ‘plural existence’ who co-inhabits a body with curator and academic Khanyisile Mbongwa. They are emphatic that Amira is not a performance (cited in The Narrative, 2018), but rather a manifestation of the artist’s school friend who endured years of domestic rape before disappearing (cited in Meet The Artist, 2016). As a queer Black woman, Amira made visible the violence Black and Indigenous people have endured in Brazil historically, continue to endure in the present and will endure for the foreseeable future. Addressing Black and People of Colour with gestures of respect and care – healing – Amira’s offers of foot washing and massage could be said to work through the archives of trauma held within their bodies. Amira is a formidable presence and taking up their offer is to submit to their touch and the gaze of onlookers. In São Paulo, their balm was applied to the foundational wounds of modernity and the labour of keeping up appearances, as epitomised in Niemeyer’s polished white pavilion.

Critical art

Bruno Moreschi, one of the seven commissioned artists, contributed Outra 33 Bienal de São Paulo / Another 33rd São Paulo Biennial (2018), an alternative online archive to the Bienal’s official dis-course. Working with a team comprised of scientist Gabriel Pereira, programmer Bernardo Fontes, producer Nina Bamberg and designer Guilherme Falcão, Outra33 ... developed twenty-two ‘actions’ over the course of the Bienal, organised around four broad questions: ‘What is presence today?’, ‘What do non-experts have to say?’, ‘What reverberates?’ and ‘What is left?’. The archive also employed algorithms and Artificial Intelligence to ‘decode’ and respond to material collected by mediators and audiences, expanding their possible readings.

Moreschi insisted that Outra33 ... was not out to prove anything, but simply to gather experiences that are conventionally overlooked. The action that seemed most relevant to Pérez-Barreiro’s prioritising of affect was ‘Audio guide: more voices’, in which the Bienal’s invigilators, maintenance staff, installers and administration were interviewed for inclusion in the official audio guides. These mini-portraits of the people whose work is often hidden by the exhibition-spectacle demonstrate how the aesthetic experience of art can trigger self-reflection, puzzlement and identification. Crucially, the interviewees were not ‘arts professionals’ but workers in arts institutions who are striving to make a living, improve their material conditions and make spaces for joy.

Critically, Outra33 ... gathered for posterity evidence about the social and political context in which SP33 occurred. The action ‘Coup d’État’ collected documentation of political manifestations that occurred during the exhibition, with Moreschi noting that the ‘dismantling of the fragile Brazilian democracy is still underway.’ Another archive entry, ‘The biggest work of the 33rd São Paulo Biennial’, reposts documentation by local graffiti artists who tagged the pavilion’s façade early in the morning of 21 October 2018. While the Bienal was commendably free to visit and has since its inauguration in 1951 developed an enviable mediation program, these actions indicate how SP33 was understood from those beyond the art system as a symbolic site for reflection and intervention. I am impressed by how these non-curated activations rendered the Bienal, from the outside, as a critical arts infrastructure.

Gesamtkunstwerk

Ocupação 9 de Julho inhabits a large multistory complex in downtown São Paulo. The building has been squatted several times since the 1990s, with the current residents having entered in 2016. Organised by one of the city’s major housing movements, Movimento SemTeto do Centro, the building is home to around 450 people who are representative of Brazil’s working poor, migrants and refugees. One of its recent developments is an art gallery, Reocupa, in the building’s original main entrance, organised with the collective Aparelhamento. For its inaugural exhibition Reocupa hosted a site-specific installation by the renown Brazilian artist Nelson Felix, opening on 16 October 2018. On the Spring equinox, 22 September 2018, Felix suspended two seven-meter long mandacarus cacti from the gables of the building, their thorny trunks extending down towards the ground. Over twenty-four hours he produced a series of drawings in situ, resulting in mixed media works and action residues exhibited as Esquizofrenia da Forma e do Êxtase (Shape and Ecstasy of Schizophrenia) (2018). This formed part of Nelson’s contribution to the Bienal, which linked two other sites in the Americas – Anchorage, Alaska and Ushuaia, Argentina – as the beginning and end of the Rocky Mountains and ‘the back-bone of the globe’. In São Paulo, Esquizofrenia da Forma... completed a thirty-year cycle of works (Garcia, 2018).

Initially, this seemed to me as an overwrought self-mythologising act, until the artist Maíra das Neves explained how Nelson’s poetics energise the Ocupação’s strategies. Nelson’s incursion inserted significant art capital into the building, recasting the squat as high-visibility art real estate. As a site-specific Gesamtkunstwerk, it bestows a degree of protection over the building which the Ocupação can leverage as a kind of insurance against the ever-present threat of eviction. Here a drama of tactical gentrification unfolds. How does art as occupation affect those otherwise occupied and made vulnerable by an uneven globalising ‘operating system’ of which the Bienal is also a part, ‘one that underdevelops some parts of the world while overdeveloping others’? (Steyerl, 2011)

Not just a problem of the middle-class.

References

Bienal de São Paulo, ‘#33bienal (Artistas-curadores) Sofia Borges’, 23 October 2018.

Ben Davis, ‘The Bienal de Sao Paulo Makes a Bold Attempt to Change the Way We Look at Art. Can It Work?’ artnet, 17 September 2018.

Germano Dushá, ‘33a Bienal de São Paulo, Brasil’, Terremoto, 22 September 2018.

Sebastian Escalon, ‘The Black Herald’, International Boulevard, 2014.

Cynthia Garcia, ‘Full Circle: The three-decades-plus global obsession of Nelson Felix concludes at last’, New City Brazil, 6 November 2018.

Michael Greshko, ‘Fire Devastates Brazil's Oldest Science Museum’, National Geographic, 6 September 2018.

Meet The Artist, ‘Khanyisile Mbongwa’, 5 April 2016.

Outra 33 Bienal de São Paulo / Another 33rd São Paulo Biennial, 2018.

Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro, ‘Individual Projects: Aníbal López’, affective affinities 33 bienal/sp, n.d.

Sérgio Ramalho, ‘Who Killed Marielle Franco? An Ex-Rio de Janeiro Cop With Ties to Organized Crime, Say Six Witnesses in Police Report’, The Intercept, 18 January 2019.

Glenn H Shephard Jr, ‘Specters of a Civilization’, The New York Review of Books, 9 August 2015.

Hito Steyerl, ‘Art as Occupation: Claims for an Autonomy of Life’, e-flux journal, No. 30 December 2011.

The Narrative, ‘Lhola Amira: Here’s What You Need To Know About The Artist Who Calls Herself An Ancestral Presence’, 28 May 2018.