The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards (NATSIAA) is an annual exhibition held at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) since 1984. Comprised of emerging and established artists, the exhibition is developed from an open call-out, this year selected by a panel of three curators: Clothilde Bullen, Hetti Perkins and Luke Scholes. Sixty-seven works by seventy-seven artists were chosen out of over 300 applications. Among these numerous contemporary works, I have made my own narrative threads and distinctions.

Portraiture

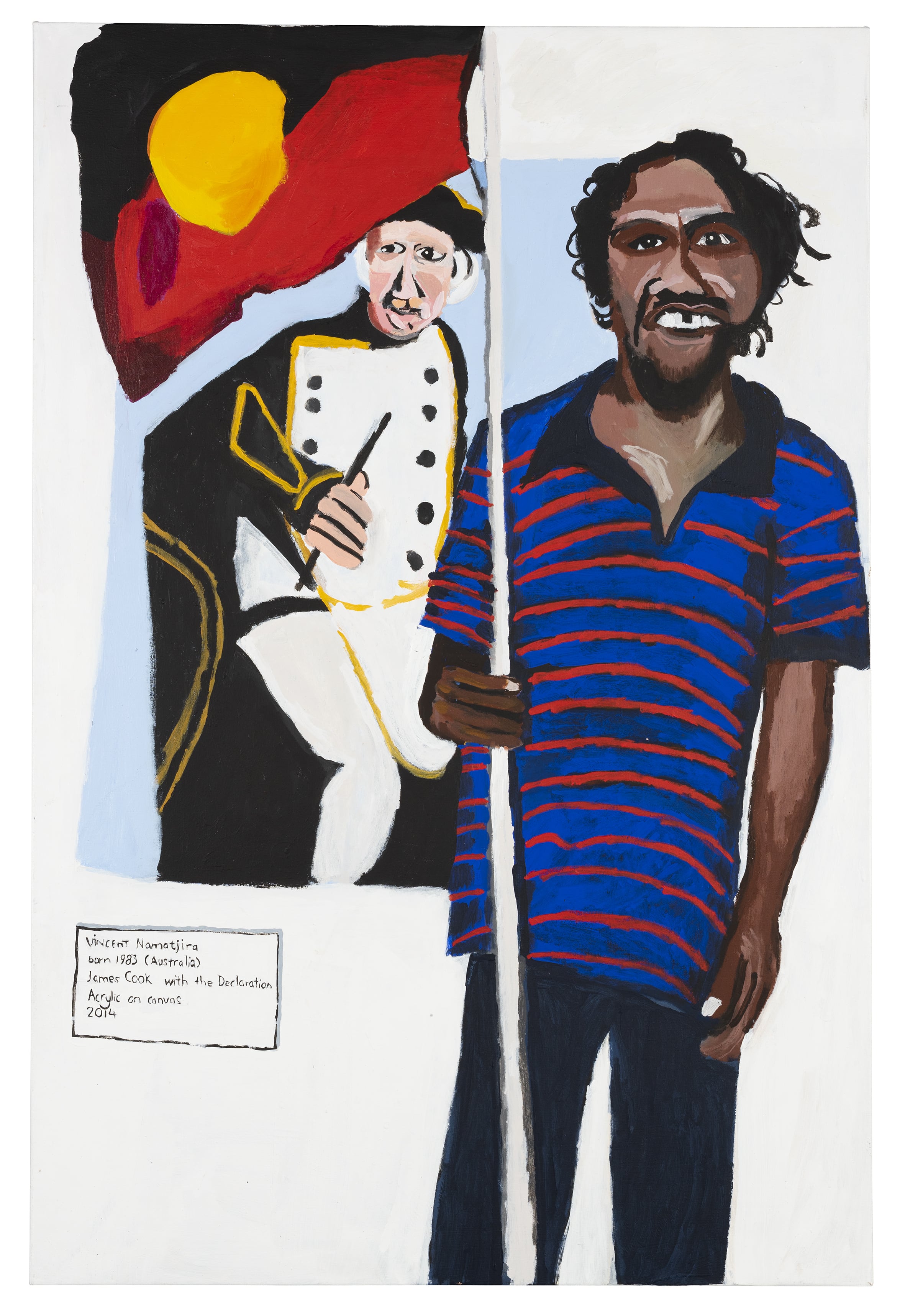

Self portrait at the British Museum (2018) is a self-described ‘cheeky gesture’ where Vincent Namatjira depicts himself standing in front of another of his paintings, James Cook — with the Declaration (2014), which was collected by the British Museum in London. Three years on, Namatjira figures himself wearing a striped short-sleeve shirt with a chipped tooth, grinning and holding the Aboriginal flag in front of his collected work; as if blowing in a strong wind, the flag partly obscures the portrait of Cook. The scene is completed by a hand-drawn didactic panel, and I am reminded of my own reliance on didactics as a viewer when standing in the exhibition. This image within an image gives an echo effect: the artist seems to mock notions of artistic and cultural authenticity. By electing his Aboriginal identity as the work’s subject, Namatjira is legitimising his own persona as a successful contemporary artist. Just as his earlier image was collected by the British Museum, Self portrait at the British Museum has a wall-sticker marking its acquisition by the MAGNT.

Another work that is arguably a self portrait is Yalanba (2018) by Yalanba Wanambi. The work is long and thin - at 2 metres it extends above and below my eyeline and is as wide as a school ruler - giving it an impressive fragility. The work’s name is that of the artist and also the sand that adorns the inside of a long piece of Stringybark. Immediately mesmerising is the way the sand responds to light, glistening in tiny flecks that sparkle in contrast to the work’s mid-tone of black. I learn the sand is unique to Bayapula on Caledon Bay and that ‘Yalanba harvests it from this place because that area belongs to his clan the Marrakulu whose identity is depicted in this work’. This depiction of clan, community and place is not how I usually think of a typical portrait, which typically puts primacy on the individual over the collective. With both this work and Namatjira’s, I feel my gaze is being deflected; I ‘know’ little more about the artists than before, complicating a general desire to ‘know’ and ‘understand’ an artist through their work.

Western symbols

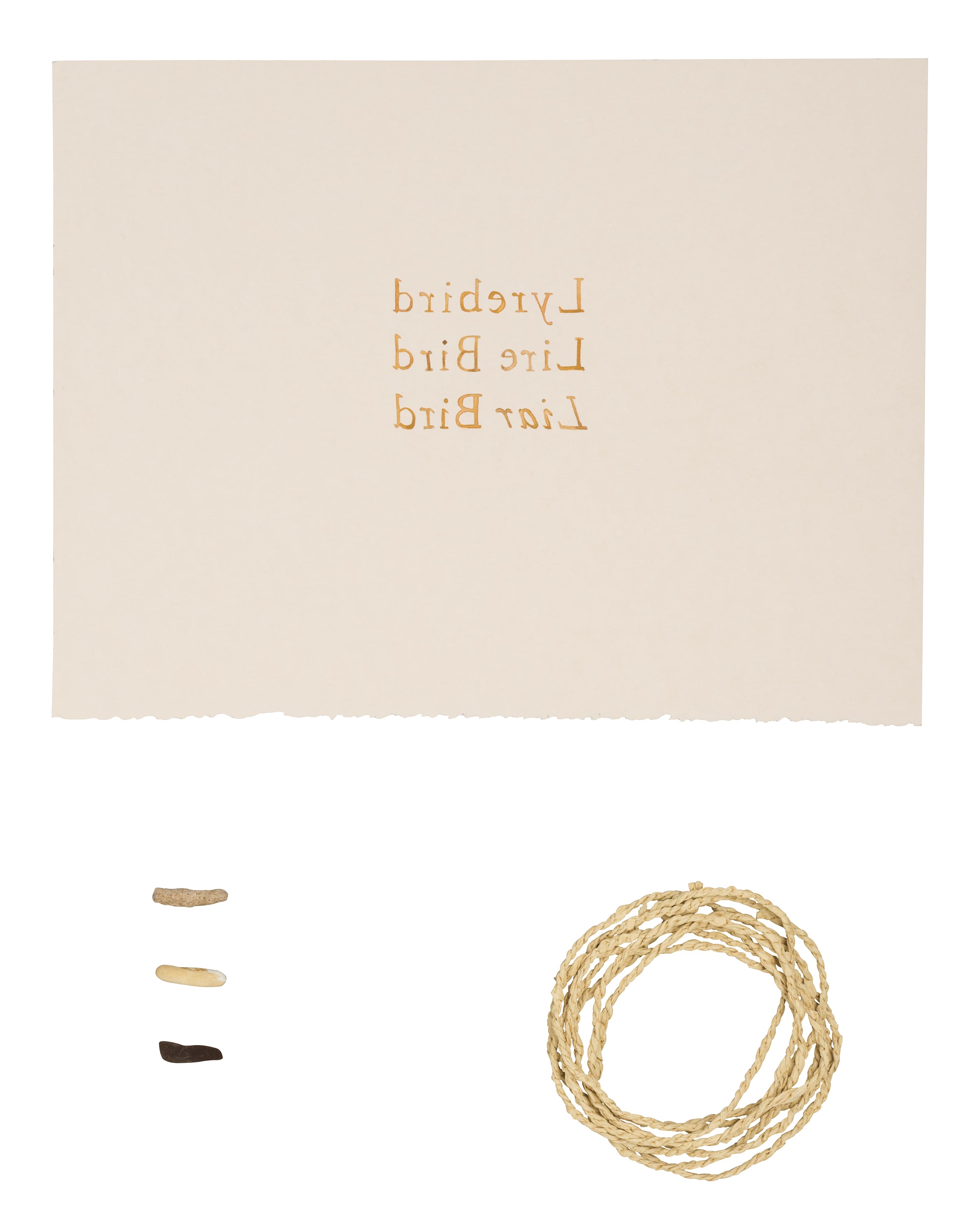

Fauna, Flesh and Feeling (2018) is a collection of small objects and text by Jenna Lee displayed in a perspex case alongside a small watercolour on paper. I discern three lines of text faintly listed in block lettering:

Lyrebird

Lire Bird

Liar Bird

The words are inscribed backwards making me work harder to read the difference between them. I remark the slow separation of one word into two in its second iteration ‘Lire Bird'. I later learn that ‘lire’ is an old English word for flesh, muscle, brawn, in contrast to skin and bone. Three objects of almost identical size are arranged in the same order as the text – vertically with small spaces between them – labelled Coral, Stone and Glass ‘found and collected on Larrakia Country’. Upon further reflection they could be many different things. An evenly and tightly woven coil of string looks like remnants of a bird’s nest; it is a ‘women’s chest adornment string’ made of natural raffia’. The artist’s collection reminds me how the worn linking of object-to-word (or categorisation) can reduce a thing, diminishing an understanding of how it is or can be.

Australian coat of arms; we were there and we were here (2017) by Niningka Lewis materialises the formal symbol of the Commonwealth of Australia; an emu and a kangaroo holding a shield that depicts the six states, surrounded by native plants. The scale of this sculpture and its handmade design lend it the air of a collectable relic, while its woven base makes it seem easily transportable, like a piece of home decor. In contrast to other royal memorabilia, the sculpture is made of woven Tjanpi (wild harvested grass), raffia, emu feathers, wool and nylon. This quixotic sculpture is a strong assertion of Aboriginal sovereignty, of the longevity of the landscape compared to the meagre timeframe of colonial settlement. The work is not only a historical critique; Lewis states that the work also serves as ‘a protest of the current incarceration of Anangu youth’.

Super Anangu (2018) by Kaylene Whiskey is a two panelled canvas of polymer paint on linen. A sky-blue background is filled with American pop idols alongside Western and Aboriginal symbols; love hearts, a snake, Boomerangs, pot plants. I love how the figures are neatly ordered but at the same time engender a fluid movement of the eyes – Michael Jackson’s face floats through the sky alongside a flying Superman and nuns holding onto red, black and yellow balloons. Nearly every person has a speech bubble that enriches the identities and interrelationship amongst the figures:

‘I’m Elton John. I grew up this minkutpa!’

‘Would you sell mingkutpa $50 price? Me, Tina Turner.’

‘Me Kaylene I love my water snake, I love my flag, and I love my family.’

The artist merges personal and mass narratives through worship in this generous and affirming work.

Place

Across the room Sally M Mulda’s Policeman taking grog, Abbott’s Camp, anywhere... everywhere (2018) features text-based daily observations made in and around Mparntwe/Alice Springs. The title sentence Policeman taking grog from the car is neatly handwritten on another acrylic light blue sky. Appearing in different sized cursive script on the simple backdrop of brown rockface is family eating early Dinner / Dog Drinking water under tree / man walking out. Words describe a scene above smaller figures going about their business between trees, buildings and cars, Palya anyway, outdoors on a bright orange ground. Mulda’s cursive handwritten text (and its varying scales) sits in contrast to the sensationalist headlines in Australian newspapers describing Aboriginal life in the Northern Territory. Mulda weighs statements differently, offering a considered insight rooted in a lived reality.

Kulilaya munuya nitiriwa (Listen and learn from us) (2017) by Mumu Mike Williams hand-writes Pitjantjatjara language with synthetic polymer paint and ink on canvas mailbags. The faded Australia Post logo that sits behind the images and scrawled words carries in my memory a few days later like an afterimage. The use of these empty containers of communication are an effective reminder of the haunting figuring of the landscape into the shape of one nation, as defined by the colonial project and its legacy of recognisable colonial infrastructures still used today. Another reminder of this is the NATSIAA’s principal sponsorship by Telstra (along with the Northern Territory Government and Australia Council for the Arts). The many different works in this year’s exhibition sample the longevity and breadth of artists working anywhere and everywhere. The ‘kulata’ (spear) that hang off William’s painting from above and below, issue a warning against complicity:

Listen to us, and learn from us Australia, okay?

Olivia Koh is an artist, she co-organises recess, an online platform for moving-image works with Kate Meakin and Nina Gilbert