Artists: Alex Selenitsch (ATMOSPHERES) and Joseph Kosuth (A Short History of My Thought).

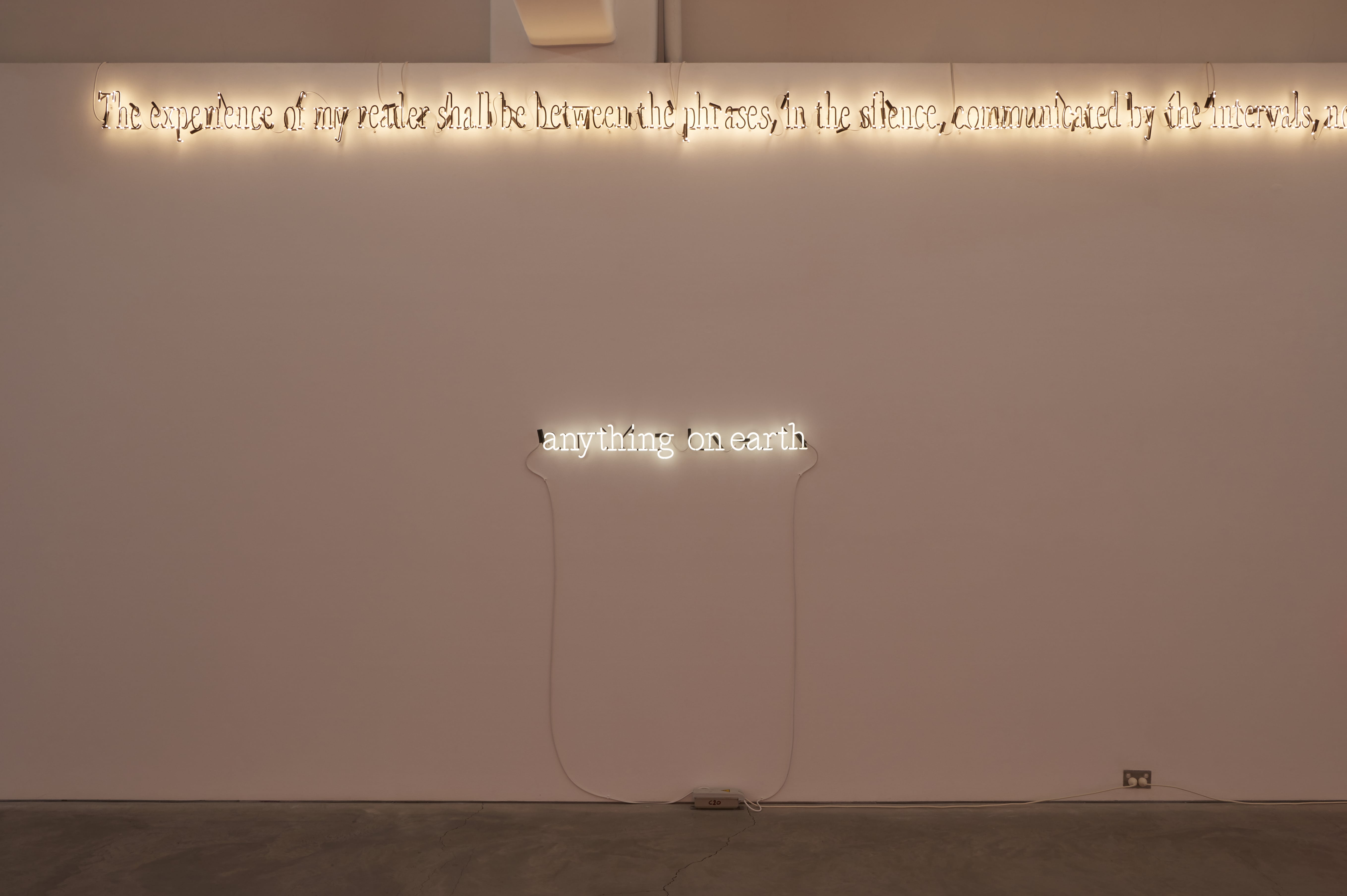

A series of neon phrases are arranged like notes along a staff, in a staggered sequence across the gallery walls. And the words hum, with the prolonged electric buzz one hears from streetlights during the night. One step past a glowing red TWENTY-FIVE, and a long excerpt from Samuel Beckett’s novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women, begins: ‘The experience of my reader shall be between the phrases, in the silence, communicated by the intervals, not the terms of the statement...’. Rendered in white neon dipped in black paint, the Beckett excerpt considers the impressions empty spaces leave on the words surrounding them. Accordingly, in Joseph Kosuth’s A Short History of My Thought at Anna Schwartz Gallery, the empty sections of gallery wall feel like punctuation marks, allowing the selected works from 1965 – 2015 to form meaning via associations.

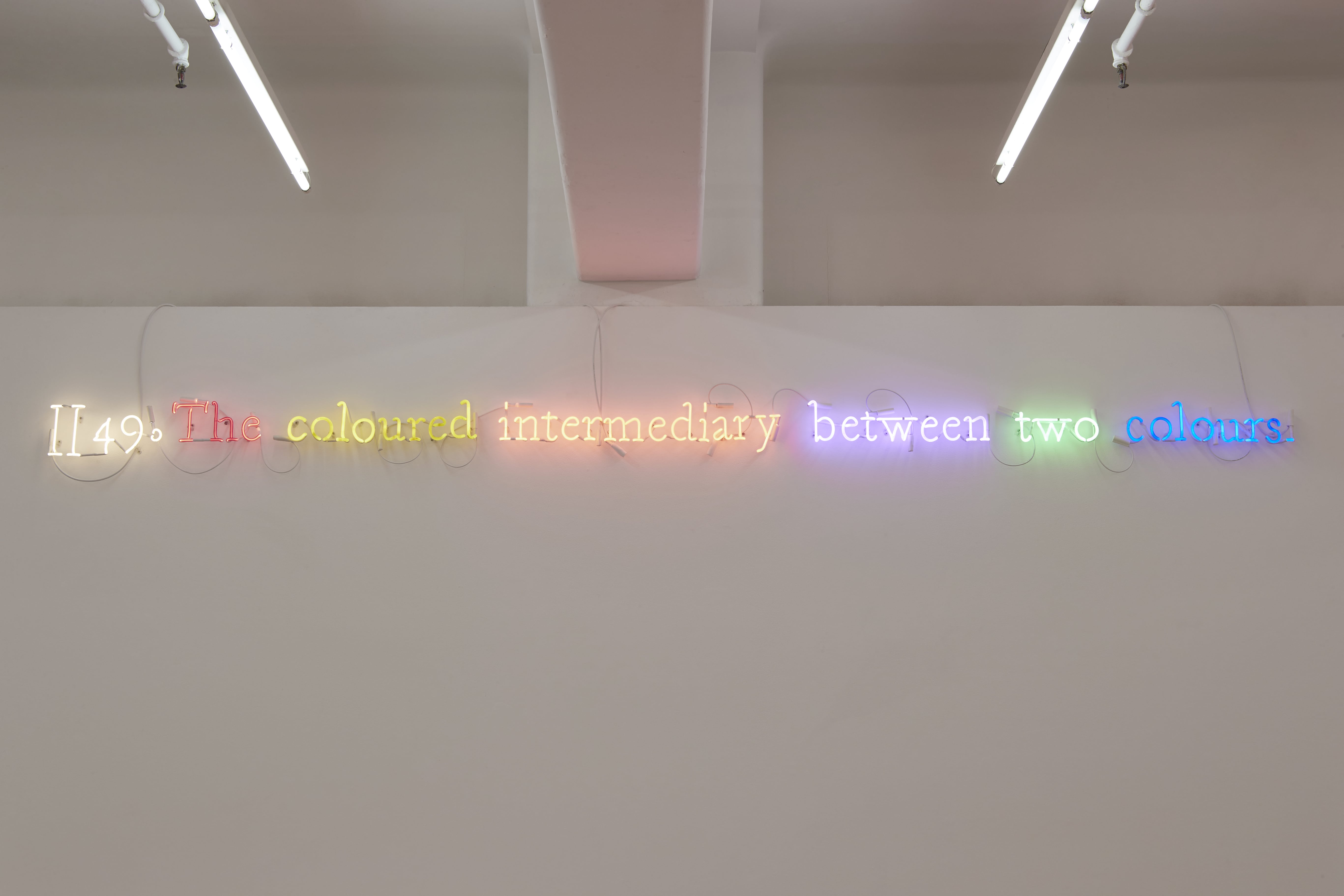

In her essay ‘Personal Narrative’, the American poet Susan Howe writes: ‘I wanted jerky and tedious details to oratorically bloom and bear fruit as if they had been set at liberty…’.1 Similarly, the overlapping words and aligned phrases – the jerky details set at liberty – in A Short History of My Thought, become one of the most interesting aspects of the exhibition. Along the upper edge of the gallery wall, a phrase from Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Colour hangs in white, red, orange, violet, blue and green neon. Reading, ‘II 49. The coloured intermediary between two colours’, the work hangs above the white neon words of J.J. (F.W. #35) (2012), and sits parallel to the black-dipped passage from Beckett’s Dream…, producing the effect – if one imagines being able to crumple the space together – of a brief poem:

In 1956, Augusto De Campos, a founding member of the Brazilian concrete poetry group Noigandres, published ‘Concrete poetry: A Manifesto’. In this manifesto, De Campos described a form of poetry liberated from linear and successive verse structures. Inspired by the pictorial language of ideograms, concrete poetry was concerned with the composition of space in relation to words. When reading a concrete poem, the eye was expected to interpret language-shapes, obstructed words and disordered compositions.

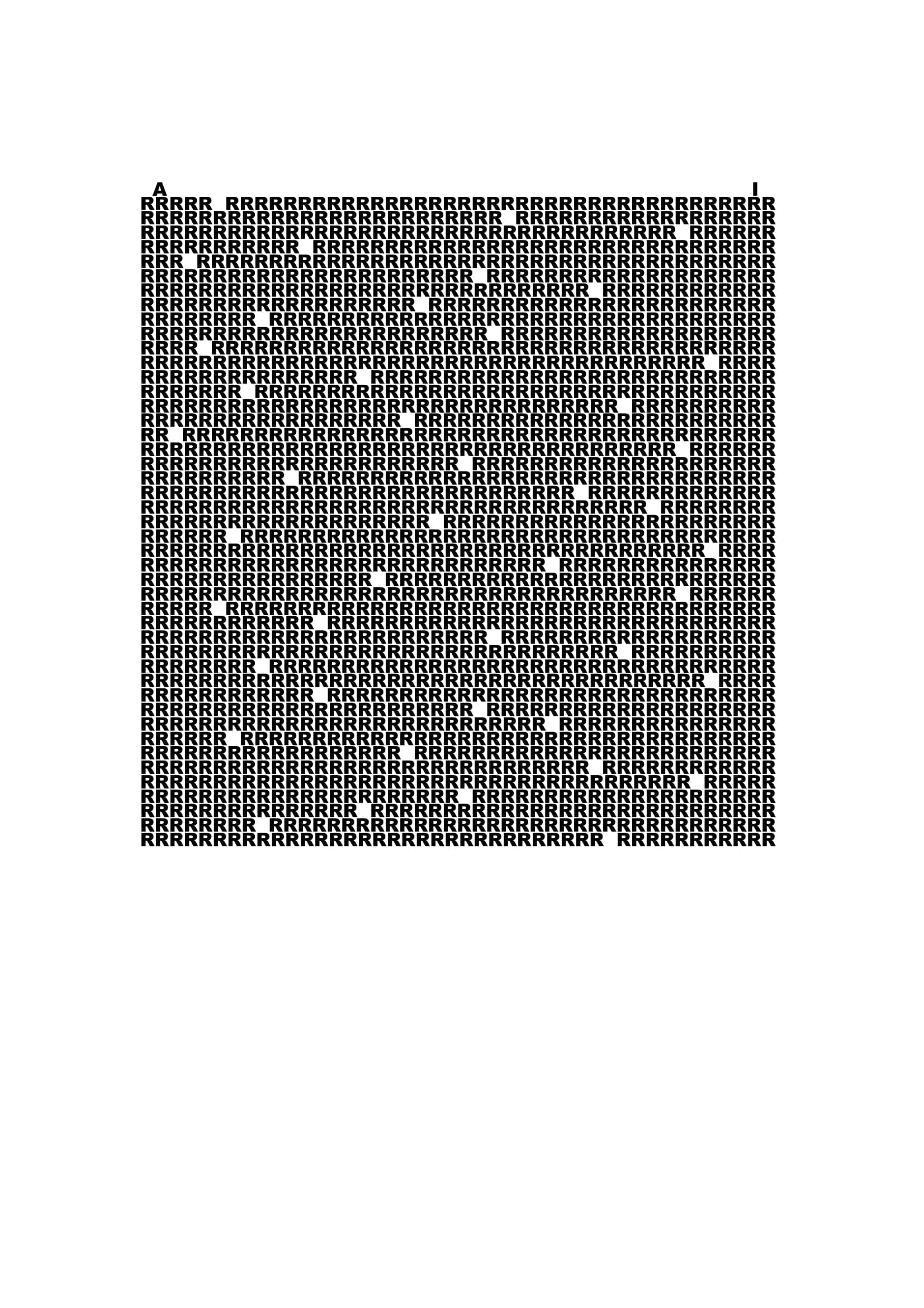

It is this visual rendering of language that Alex Selenitsch draws upon in the recent exhibition ATMOSPHERES at George Paton Gallery. The repetition Selenitsch uses in the poem R from AIR, for instance, confuses a linear reading. Starting from the upper left corner, we see the letters A and I, before our eye skims over a hum of wavering Rs, interrupted occasionally by gasps of space. Like the semi-materiality of air, the word evades us and, if we want to read it, we have to imagine the I combing through the repeated Rs and slotting into the empty spaces. A work in Selenitsch’s ATMOSPHERES, R from AIR is pasted onto the gallery wall alongside a series of single-word poems, each one disassembling a weather-related term: mist, fog, cloud, haze, smoke and vacuum.

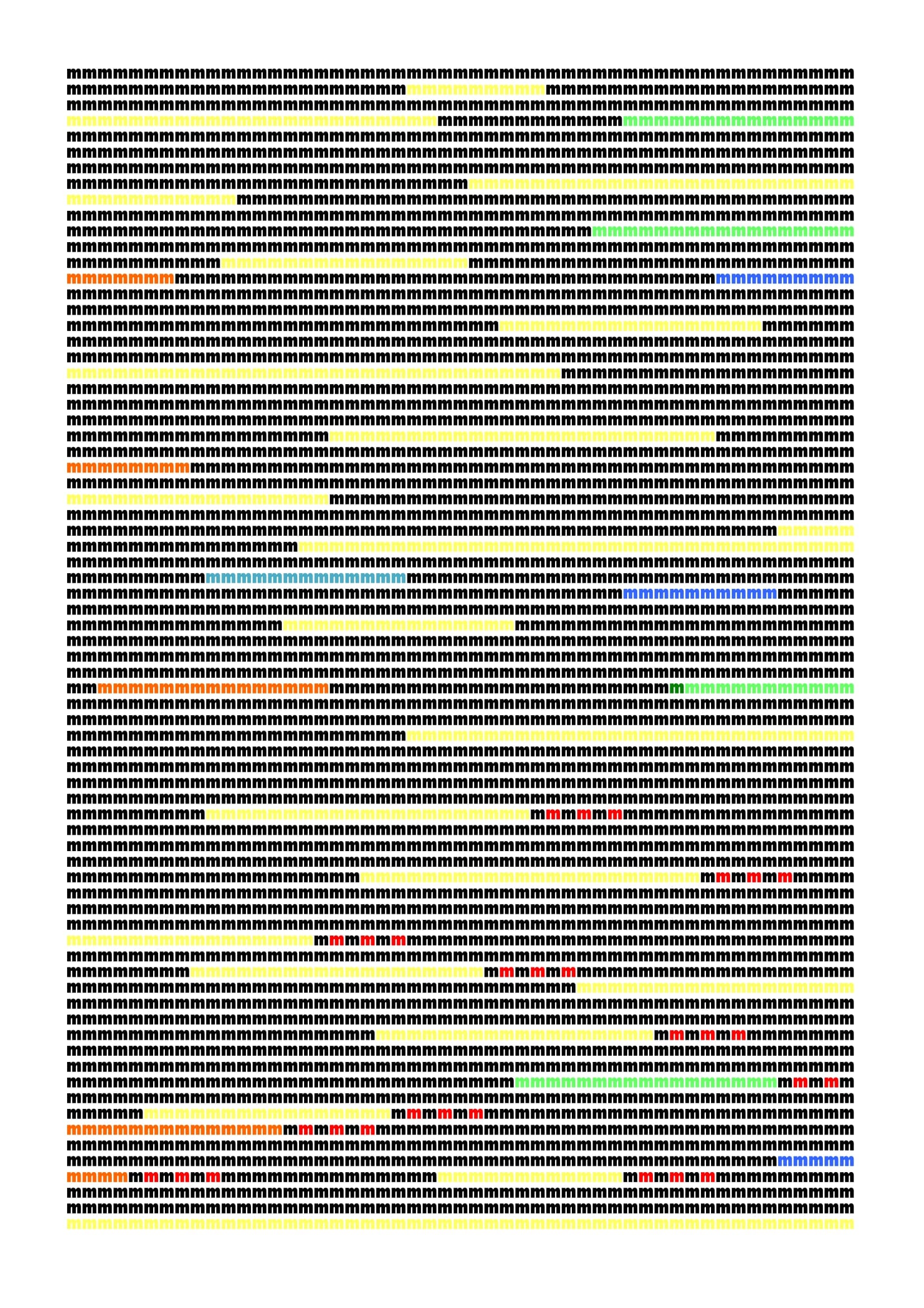

In a poem titled mFROMsmoke, a page is filled with rows of bold, lower-case m’s in recurring streaks of black, red, green, blue, orange and yellow. Rather than producing a hum similar to the R from air, the repeated m is caught during its movement between letters. As a result, it becomes a prolonged interval that stutters forward, impatiently looking for its end. Saying this, the m doesn’t just continue, unchanging across the page. Appearing in blue or yellow, the letter is the same, but this visual difference makes it ambiguous and able to evade definition.

Described by Noigandres member Décio Pignatari as ‘a general art of language’, concrete poetry aimed to appeal to the public at a time when television, cinema and neon signs were changing the way we viewed information.2 The concrete poets wanted to use everyday language as a material, to see how it functioned, and what it revealed. In Selenitsch’s poems the letters, printed using a standard printer and A4 paper, seem gleaned from the banal language of tax invoices and shopping receipts. It’s the language that surrounds us, the printed letters we use every day that can be distilled to give the impression of air or smoke, to encapsulate, as Wallace Stevens writes ‘the world as word’.3

Kosuth’s excerpt from Beckett’s Dream… runs along nearly an entire length of the gallery wall. Its opening words, quoted at the beginning of this piece, refer to the intervals between phrases, words and letters. The blank spaces, breaths, hums and stutters that draw language together. The jerky details, that bloom between the flowers. Hanging below Beckett’s Dream…, Kosuth’s A C (J.J. F.W.) (2011), glows in muted white neon:

Robert Albazi is a Melbourne-based writer. His work has appeared in Artlink, Real Time Arts, Art + Climate Change and other publications. In 2016 he was assistant editor for the Lisa Radford anthology ‘Aesthetic nonsense makes commonsense, thanks x’, published by Surpllus.