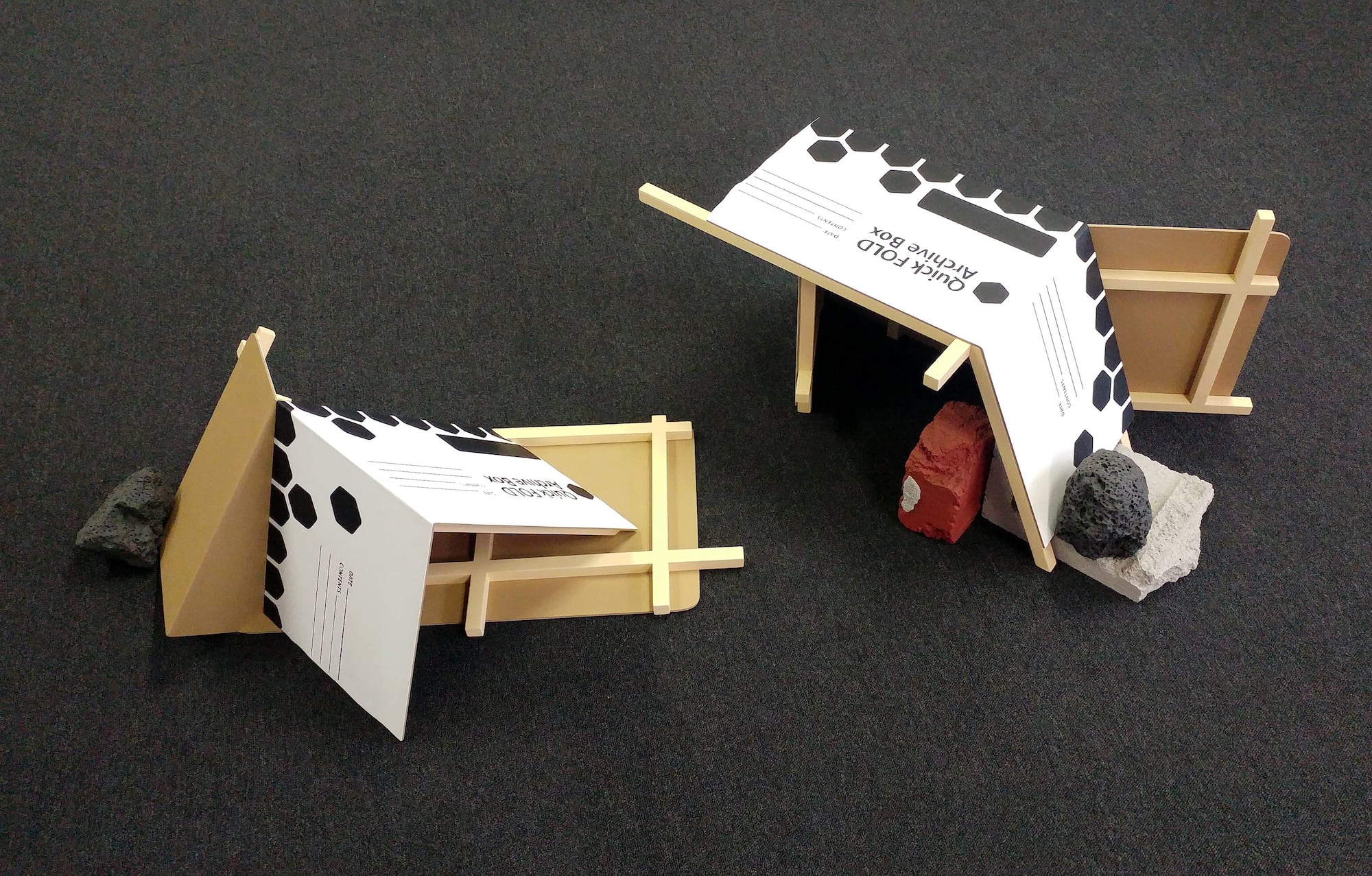

Recently I went to see Carly Fischer’s I feel the earth move under my feet (2018) in the group show Groundwork at Maribyrnong’s Living Museum of the West Visitor Centre. The Museum of the West is a small social history museum, run by dedicated amateurs devoted to Maribyrnong’s past, first as a place where armaments were made for the two World Wars and more recently where concrete pipes were constructed for Melbourne’s sewerage system. Amongst the vitrines and glass-fronted bookcases holding photographs and documents Fischer’s piece sat on the carpeted floor, nondescript and at first sight almost indistinguishable from the other as yet unclassified material brought in by local historians.

I feel the earth move is made up of two packing boxes marked ‘Quick Fold’ sliced open and bent over laminated sheets of pine with a lattice backing, the whole weighed down at various points by black painted rocks and broken besser blocks. At first the work looks random – indifferent, unconsidered, barely rising off the floor - reminiscent of the unchecked plague of ‘scatter art’ that infests Melbourne’s artist-run spaces and smaller institutional galleries.

But though Fischer’s art flirts with this, it never entirely succumbs. There is always, even in a piece like I feel the earth move, a subtle hint of compositionality, a meaningful articulation between the different parts of the work that speak to each other, maybe not always in sympathy but at least in disagreement. The earth might move, bringing down everything around it, but something will always rise again. Fischer’s work over the course of her career strikes us like the return of something from the dead, which as much as anything means something ascending from the horizontal and assuming the vertical, no matter how broken or bent over.

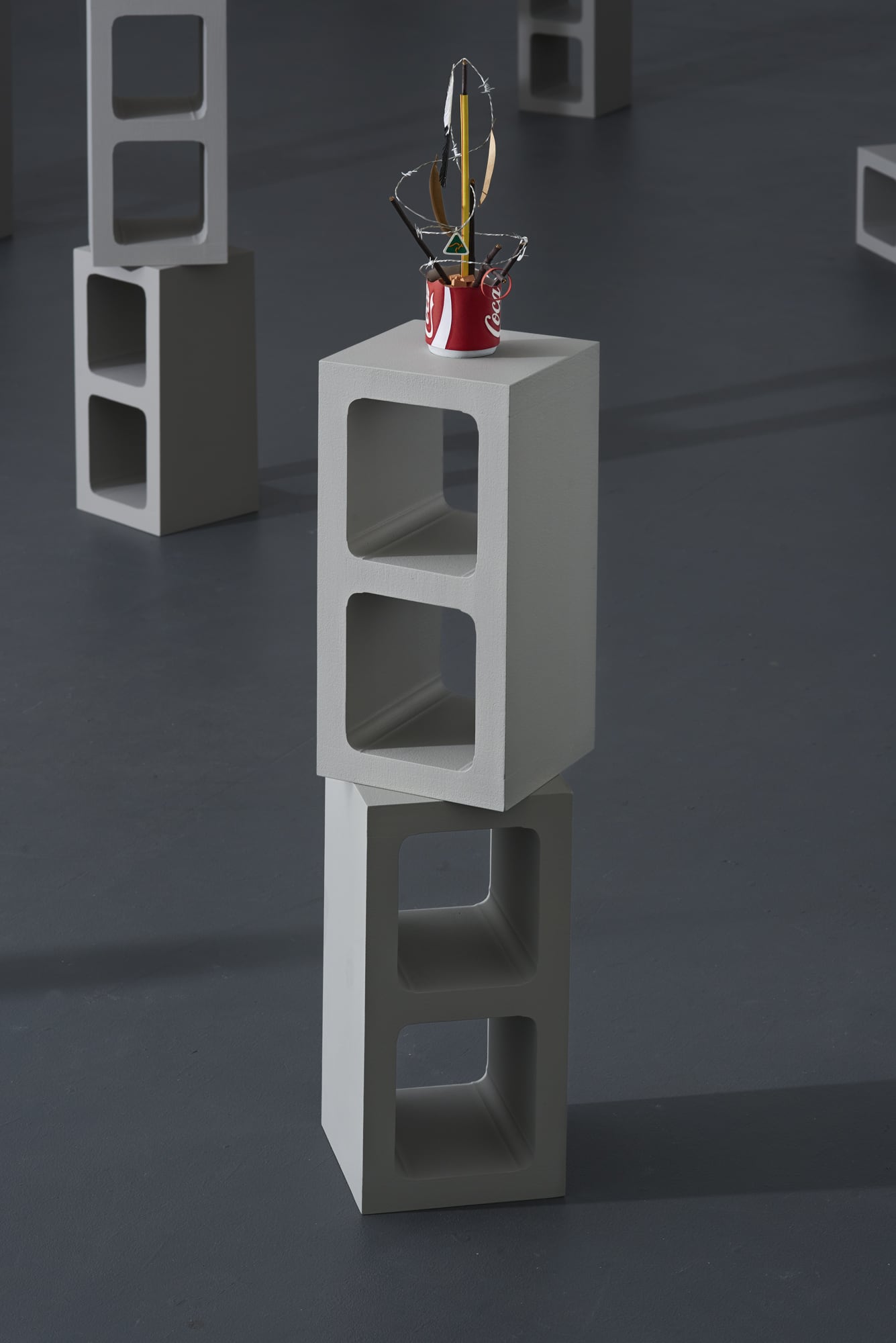

The first work of Fischer’s I encountered was the exhibition Total eclipse of the heart (2014). I think I was down in Melbourne for a job interview and after it was over but before I had to catch my plane, I found my way into This Is No Fantasy Gallery on Gertrude Street. There in the brightly lit concrete space were some ten delicate arrangements of items inside cut-open beer and soft drink cans perched on top of variously arranged besser blocks. There was an obvious contrast between the intricacy of the objects within the cans and their subtle relationships (from memory, a series of red feathered darts behind a road sign for kangaroos crossing, HB pencils with barbed wire wrapped around them) and the anonymous brutalism of the concrete blocks.

However, the thing that struck me about the work – and that has remained with me ever since – is that here was something that was holding itself forward as sculpture. Again, the small assemblages of objects were internally articulated; their separate parts were self-supporting, leaning against, or on occasion away from, each other. And the drink cans in which they were set and the concrete blocks they were on top of functioned like old-fashioned sculptural plinths, removing the work from the quotidian every day and even from the physical environs of the gallery (for all of the rhyme between the concrete of the besser blocks and the floor).

This struck me because sculpture is a much-misunderstood medium in today’s artworld. For evidence of this, we only need turn to Monash University Museum of Art’s 2017 exhibition The Future Eaters. Ostensibly a show about sculpture, in fact very few of the works in it were actually sculptures – and didn’t even meaningfully raise the question of what is sculpture – but, rather, were installations: arms dangling from walls, a machine that poured water into soil, a severed computer cable in a clear acrylic cube. Maybe the only work that fully qualified as a sculpture was Anna Uddenberg’s Savage #2 (2017), the striking Berniniesque figure of a woman leaning back off her suitcase in ecstasy, her long black hair almost touching the ground. (It was important that her hair didn’t touch the ground so that we had an illusion of her weightlessness, that she didn’t need to be supported but held herself in endless contrapposto.)

Needless to say, there are several responsibilities for a work claiming – or being claimed – to be sculpture. First among them is that it is somehow comparable to while nevertheless being different from what has previously been called sculpture. Perhaps the thing that distinguishes sculpture from installation is its sense of internality or composedness. A sculpture is not merely another object in the world; it is an object that declares its own space and separation from the world. It is not literal and embodied but metaphoric and disembodied. It relates not so much to the world around it or the space in which it is installed but first and foremost to itself, seeking to make the decisions behind its composition explicit to the viewer.

It is this that strikes us about Fischer’s work, even from the beginning. Obviously, as a young sculptor, she was influenced by the work of Mikala Dwyer. We can see this in the row of small objects leaning against the walls of the gallery in Life tends to come and go (2011), like the silicon numbers in Dwyer’s Hollow-ware and a few solids (1995); or in the expanded white plastic bags in Don’t forget me (2013), like the heat-blown plastic bubbles of Dwyer’s Shape of thoughts own making (2007). Yet there is a small but decisive divergence from Dwyer: Fischer inserts her objects in paper bags or plastic bags in soft drink cans. What this makes clear is that, at the last moment, Fischer is a sculptor while Dwyer is an installation artist (and a very significant one).

Another fascinating aspect of Fischer’s practice is that her works are not simply sculptures; they are allegorical of the very situation of sculpture in contemporary art today. Her pieces are fragile, delicate, seemingly provisionally put together and in immediate danger of falling apart. The containers in which she houses them (cut-off drink cans, wooden palettes, stacks of boxes or bricks) are not only what define them as sculptures, but also speak themselves of the particular separation from the world that sculpture requires. In her own accounts of her work, Fischer details a series of issues that they are about – globalisation, the Australian landscape, environmental awareness. But the point is that all of these are filtered through the necessary requirements of sculpture. They have to, as it were, make the jump over to the other side after which they are no longer quite the same.

Over the course of her career, Fischer’s work has seemed periodically to assemble and disassemble itself, going from more refined and elaborate sculptural work (Creating false memories, 2016) to more informal and uncomposed (We’re all in this together, 2012) and back again. Once more, this echoes the way that the medium periodically has to rethink itself in order to survive, to find the ‘new’ conditions for sculpture that are also faithful to the old. And in the end this is the true topic of Fischer’s work and what all of its content and technique ultimately go towards: what is it to make sculpture today?

Dr Rex Butler is an art historian, writer and Professor (Art History & Theory) at Monash University.