.jpg)

Artists: Anang Saptoto, Bambang “Toko” Witjaksono, Cinanti Astria Johansjah, Cut and Rescue, Handiwirman Saptura, Iwan Effendi, Julia Sarisetiati, Kokok P. Sancoko, Krack, Priyanto Sunarto, and R.E. Hartanto.

Curator: Grace Samboh

Featuring 13 artists from Jakarta, Yogyakarta and Bandung, this is an uneven but energetic exhibition of Indonesian paper works curated by Grace Samboh. Her curatorial proposition in the catalogue essay, ‘How to use an exhibition to make thoughts visible and real?’, doesn’t provide much in the way of conceptual signposting, but once you accept that there is no grand idea undergirding this show other than the works’ medium - paper - and timeframe - the noughties for the most part - there are pleasurable discoveries to be made.

These pleasures, when they come, are of an accidental, offbeat quality. For all of the curator’s textual wishywashiness, she has an eye for contrasts. At the exhibition’s best, it offers unexpected and highly specific insights into Indonesia, its currents and contradictions; Cut And Rescue’s psychedelic collages inspired by drug paraphernalia (Insect Trainer (Re-edit), 2014–17) sit alongside R.E. Hartanto’s very correct watercolour portraits of working professionals such as geologists and poets (New Indonesian series, 2017). Whether planned or not, the mood Samboh evokes in the show is spiky and unpredictable, veering from the stately sculptural formalism in a pair of pink inflatable paper lungs, Inhale/Exhale (2012), by senior artist Handiwirman Saputra, co-founder of the country’s pioneering contemporary art collective Jendela Art Group, to artworld pranks, such as the famous Price List (2009) by Bambang ‘Toko’ Witjaksono for the Jogja Biennale in the same year. This bound booklet featuring a list of fake prices for artworks, sometimes down to the rate per square inch of canvas, had confused gallerists and collectors during what was a supposedly non-commercial event.

Most of the exhibits hail from Yogyakarta, the laid-back boho city and Indonesia’s cultural capital. Iwan Effendi, co-founder of the city’s renowned puppet theatre group Papermoon, injects a dreamy moment through a pair of comet-shaped marionettes with ghostly papier mache faces and tissue-thin tails (The Puppet Moment, 2017). The mood quickens with the younger artists. In the series Dream Land (2014–2017), printmaking collective Krack! reproduces 26 Indonesian ads and propaganda from 1900 to the current day, capturing snapshots of a restless populace as it moves from colonial rule to independence and finally full-fledged capitalist society. Through their work, you see what Indonesians wanted in the 20th century. In the 1930s, objects of desire included cigarettes; in the 1950s, petji, a small round velvet hat associated with the nation’s second president Suharto; and in the 1970s, Indomie, the still-ubiquitous instant noodle brand whose copywriters proclaimed was “the national food full of health”.

With the Jakarta artists, things run underground and get more gleefully politically incorrect. Tapping into the gambling scene is Julia Sarisetiati’s Sharing Strategies of Uncertainty (2013), a video featuring four full-time punters having a conference about their mathematical systems for predicting the winning numbers of the lottery. A separate chart details their formulae. More pseudo-science goes on in art collective Cut And Rescue’s multimedia installation Insect Trainer (Re-edit) (2014–2017). ‘We try to remain unknown by others and to move in the background’, goes their cheerfully paranoid motto for this project, initiated in 2014 to learn survival skills from cockroaches in the face of impending apocalypse. This most recent iteration comprises collaged artworks printed onto perforated paper inspired by LSD dose sheets, where tiny tabs are broken off and put in the mouth. The images are random, frenetic, drawn from some druggy mental-scape: insects upon insects, cartoon scenes from Pinocchio, the spliced image of an eyeball.

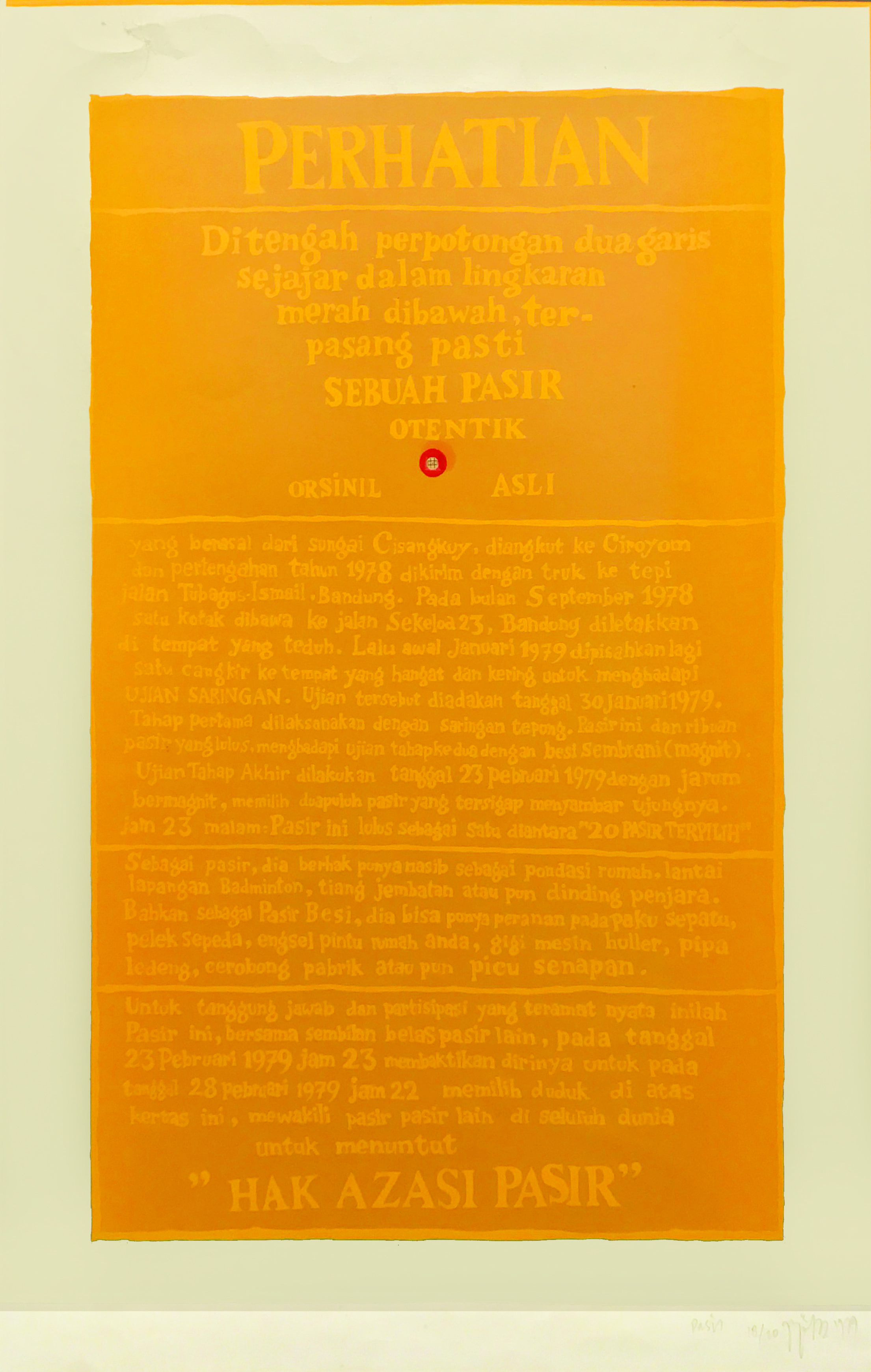

From seedy Jakarta we move to cool-climed Bandung, where the exhibition throws up another gem, a charismatic and enigmatic silkscreen print called The Sand’s Right (1979) by Priyanto Sunarto. On a yellow document, a little speck of dirt from West Java sits in a red circle. The rest of the print features an Indonesian text detailing the grain of sand’s origin story, its potential uses, and its final purpose, which is to “devote (itself) to choose to sit still on this (piece of) paper”. Finally, on behalf of all sand in the world, it goes on to declare “the rights of sand”.

This work was made almost 40 years ago yet feels extraordinarily relevant, though its message remains inscrutable. What exactly are the rights of sand? For sure, sand is a hot topic now. As one of the most valuable resources of the 21st century, it is often discussed in terms of its scale, in metric tons, and measured by its drift, transnational movements which are themselves a potential source of geopolitical anxiety. (It is worth noting that in 2007 Indonesia banned exports to land-reclamation-mad Singapore for purportedly environmental reasons.) In contrast, Priyanto takes the microscopic approach by singling a grain of sand out from his hometown, stopping its circulation and declaring its commitment to “sit(ting) still”. Does sand have a moral and legal entitlement? What permission do we need to seek from it? Resistant to the end, the work offers nothing but a defiant silence.

Adeline Chia is an arts writer based in Singapore and the associate editor of ArtReview Asia.