Curator Tirdad Zolghadr once remarked that if you are working class in the arts you feel inadequate, and if you are middle class you feel embarrassed.1 Provocateur that he is, Zolghadr’s passing comment hits a nerve. Why is class so hard to talk about? Why is it that with such a sophisticated vocabulary on racial privilege and queer perspectives we struggle to find a place for the ‘c word’ in identity politics? Stranger still, how is it that we might dedicate hours to reading Marx and Virno (or pretending to have read Marx and Virno) yet still mumble the name of our high school? While we might hear small whispers from time to time, disguised in the topics of ‘labour’ or ‘economy’, there is still a general aphasia when it comes to speaking about class in art.

I should start this review by admitting that I am one of the embarrassed. I’ve had an easy time, as I suspect a lot of the art world has. Despite its claims to counter-culture, contemporary art in the West is, at least in part, a system which arose in response to the free time of the middle class. It’s much easier to visit a gallery when it takes you 15 minutes and not an hour to get there; or you if start work at 9am and not 4am. Easier still if you can recall visiting as a child ¬― a memory likely to feature two parents and a babyccino. A career in the arts is much the same. Choosing to study a BFA or BA or is often less a declaration of intellectual rebellion as it is the sign of a well-funded safety net. Similarly, the expectation of unpaid internships or self-funded shows rests on a certain understanding of the class status of recent graduates. Class — that murky vector of cultural and economic capital — is far more integral to art than we may want to admit.

‘Class Act’ is not coy about its topic. Including the work of seven artists — Daniel McKewen, Raphaela Rosella, Kay Abude, Gerwyn Davies, Rhiannon Dionysius, Leen Rieth and Llewellyn Millhouse — and curated by Lisa Bryan-Brown, the exhibition puts aside the expectations of this embarrassed mass to explore the inequalities of Australia and its art world. The show is refreshingly frank about class and, in doing so, offers a truly novel interpretation of the artists’ work.

Across her practice, Kay Abude compares the factory and artists’ studio as similar, yet differently classed, sites of production. When Abude’s parents emigrated from the Philippines to Australia in the late 1980s they had to transition from white collar jobs to factory work. The prints exhibited in ‘Class Act’ were taken at a durational performance Family Line (2010) in which each member of Abude’s family sat in the gallery and cut white A4 paper into the size of $100 notes. A pun on both ‘making money’ and the ‘work of art’, Abude shows how easily class inflects the value of labour. In the gallery her family are postmodern performance participants; yet doing a similar task in the factory they are ‘unskilled’ workers. Similarly, Leen Rieth pokes fun at the art world’s implicit middle-class conventions. You and me [3] (2018) comprises a small neon circle and a typed list of all the steps required to make it, including ‘40+ emails’, ‘8 years of conversations with the curator’ and ‘a “university accent”’. As Abude and Rieth suggest, e-flux cultural clout is perhaps little more than an expression of class.

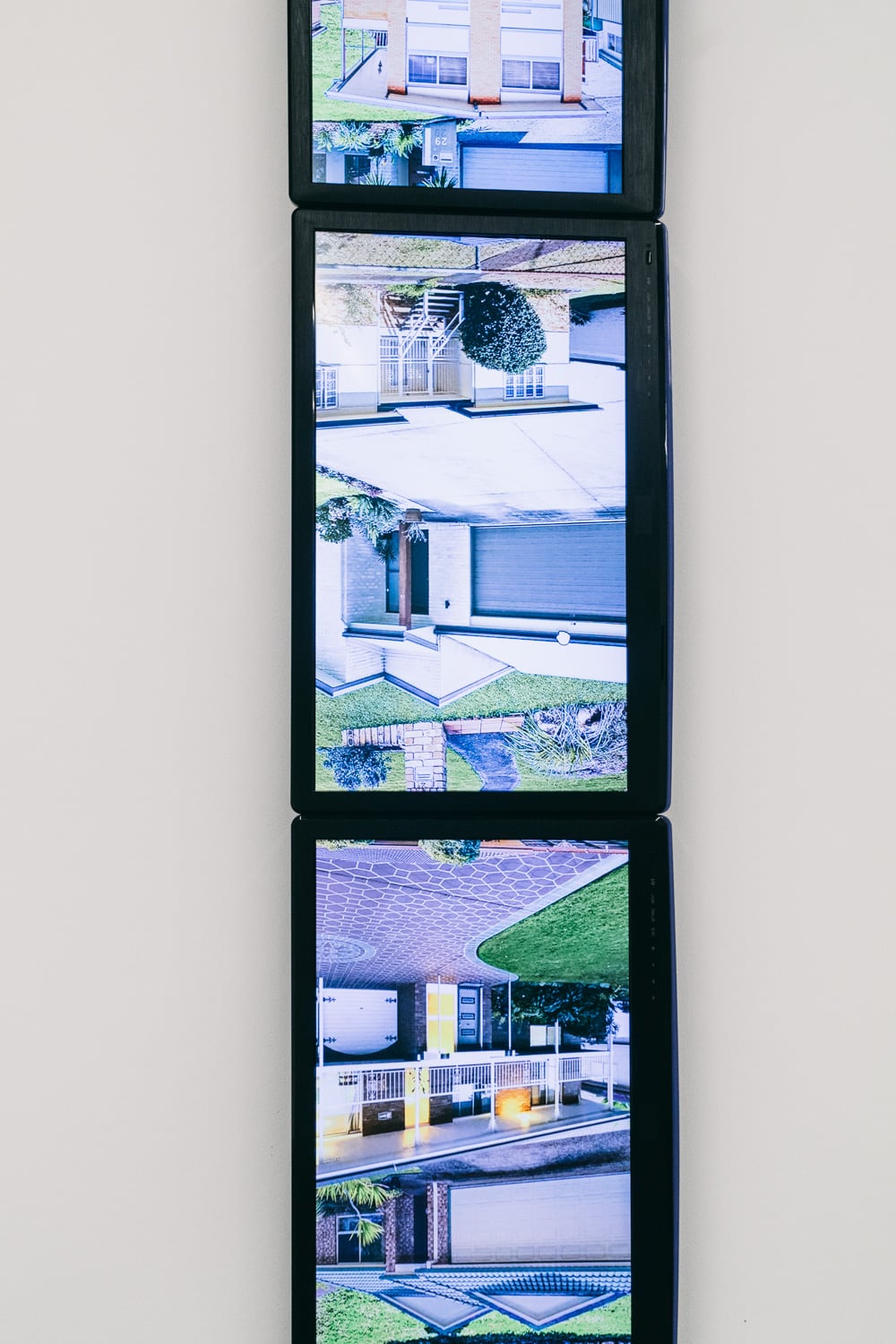

In another direction, Daniel McKewen’s video installation Climbing (2018) examines Australia’s ever-steepening housing market and class mobility. McKewen’s previous work appropriates the visual signifiers of Big Banks and the Global Finical Crisis, and while we are all feasibly victims of the neo-liberal economics represented in his previous work, Climbing looks more closely at the concrete impacts of Australia’s current class system.

Across five screens, the artist transposes images of Brisbane properties from real estate pages so that they appear to loop in an endless scroll. McKewen combined these images in order of postcode, such that the imagined cursor scrolls through a spectrum of properties and their associated class. ‘Climbing’ refers to the fantasy of quick social mobility, that one might settle for an unfashionable postcode in purchasing their first home yet gradually inch forward to the coveted inner suburbs. Yet Mckewen’s kaleidoscopic and disorientating video says as much about changing class expectations as it does class geographies. While the size and location of your house have always indicated a particular social bracket, it is only recently that middle-class Australians have faced the question of actually owning their homes.2 McKewen’s shiny found images carry a certain anachronism – a vision of the Australian dream slipping from fingers the young middle class as their parents buy up the remaining property.

As Australia’s middle class swells to create a bloated diamond-shaped class structure, it is easy to forget working class perspectives. Raphaela Rosella has spent the last decade capturing the impact of poverty and early motherhood on the women in her family and boarder community. In her quiet and candid images, Rosella inverts a long documentary tradition and its implicit class dynamic. Historically, it is through the eyes of an outsider that we see scenes of poverty: the finically comfortable artist takes a trip down to the lower class, shoots images of hungry looking children and worn-out mothers (à la Dorothea Lange), and then returns to their own class stratum to develop and sell the photographs.

In contrast, Rosella looks from the inside. The artist began her series on young mothers after her twin sister fell unexpectedly pregnant at a young age. She recounts, ‘For many of my friends, becoming a parent young was not a ‘failure of planning’, but a tacit response to the choices and opportunities available to us.’ The works selected for ‘Class Act’ all depict mothers affected by incarceration, breaking yet another fraught silence on the effects of class. Some women in these photographs gave birth in prison, whereas others struggle while the father of their child is in jail. Rosella’s photographs bring to light the physical marks that class imparts on the body. Stretch marks and pelvic prolapse shift class from the realm of abstract politics to visceral reality. Further, her work reveals the gendered, and often racial, experience of class. Because, of course, one’s class identity never tells the full story — we only have to consider the different experiences of a male and a female bartender, or a nurse with a non-Australian accent and one with, to understand as much. In this way, Rosella depicts class as one node in the many intersections of political identity, offering nuance where traditional discussions of ‘class warfare’ cannot.

Bryan-Brown’s exhibition is one of the few I’ve seen recently that makes a real argument about the artwork it includes. Across the show, the issue of class is treated in new and insightful ways, without sheepishness or affected sentimentality. In doing so, ‘Class Act’ speaks not only to real-world social divisions but also, obliquely, exposes the awkwardly class-determined nature of contemporary art.

Sophie Rose is currently Assistant Curator at the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA).