![Image 03: Frédérich Nauczyciel *A Baroque Ball (Shade) [Paris Ballroom Scene & Dale Blackheart] 2014, digital video 5:13 minutes. Courtesy and copyright the artist.](/old-images/reviews/89.cover-versions/fred.jpg)

_Artists: Arthur Merric Boyd and Neil Douglas, Michael Candy, Maria Fernanda Cardoso, Marco Fusinato, Percy Grainger and Burnett Cross, Yuki Kihara, The Kingpins, LOUD+SOFT (Julian Day and Luke Jaaniste), Frédéric Nauczyciel, SodaJerk vs. The Avalanches, Super Critical Mass, Christian Thompson, and Jemima Wyman.

Curator: Anna Briers

The oft repeated saying ‘imitation is the sincerest form of flattery’ suggests that to imitate is to unintentionally compliment the original. In the work of the artists featured in Shepparton Art Museum (SAM)’s Cover Versions: Mimicry and Resistance, however, imitation is utilised as a conscious and deliberate strategy.

A ceramic plate from the SAM collection, made by ceramicist Arthur Merric Boyd and decorated by Neil Douglas with the image of a lyrebird, is presented as the starting point for the exhibition. The lyrebird is a native Australian animal known for its uncanny ability to imitate both natural and artificial sounds from their environment. In this vein, music – a medium that commonly uses the cover version, remix and mash up – features heavily throughout the works, and is perhaps, as suggested by SAM Director Rebecca Coates in her catalogue foreword, a way of appealing to the local Shepparton community. Although the curatorial focus on music sets up a rather narrow framework for a discussion of subversive artistic strategies of imitation, the strength of the included works makes up for this overall.

The first room, concentrating on imitation in the natural environment, was somewhat underwhelming. It was with the contemporary artists who utilise imitation, impersonation and mimicry as a social or political force that the exhibition really found its stride. Yes, mimicry exists in the natural world, but it is more interesting when humans consciously employ it as a tactic.

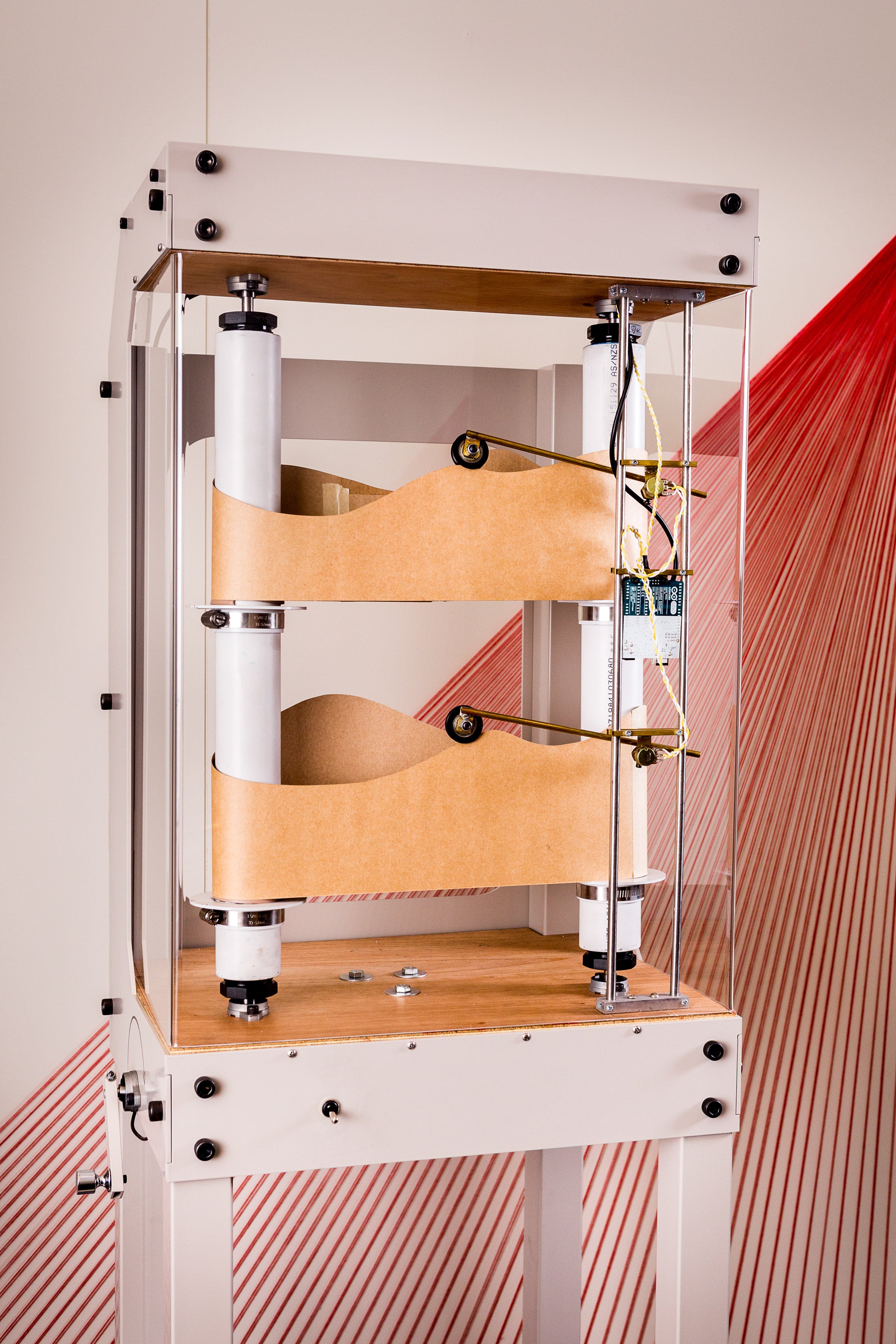

Weaving through the exhibition is a deliberate play on the multiple layers of reference, reproduction, mimicry and appropriation. Standouts include Michael Candy and Rosalind Hall’s Kangaroo Pouch Tone Tool (2016), a replica of Percy Grainger and Burnett Cross’s ‘free music’ instrument from 1952, designed to emulate the sounds of rolling waves; to LOUD+SOFT (Julian Day and Luke Jaaniste)’s installation of seven turntables modified to play concurrently and out-of-sync the 1981 cover version album Hooked on Classics; to drag king performers The Kingpins’ lip syncing parody of Run-DMC’s Walk This Way video clip, which was itself a cover up of the original Aerosmith song; to Frédéric Nauczyciel’s video featuring dancers of the Paris queer and trans ballroom scene voguing (a scene rich with layers of appropriation) to a soundtrack of Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, one of the most reproduced pieces of classical music; and the music video collaboration The Was (2016), by digital collage artists Soda_Jerk and The Avalanches, musicians renowned for sampling and mash ups.

The most interesting works in the exhibition use mimicry as a tool to draw attention to or subvert the dominant gaze. In VERSUS (2002), The Kingpins, a group of four female artists in drag, perform consciously for the camera in a cover of the Run-DMC’s Walk This Way video clip. Their overt comic parody of the machismo we are habitually exposed to on our screens serves to reframe the male gaze through that most ubiquitous of genres, pop music, a typically male dominated industry.

Christian Thompson’s powerful Museum of Others (2016) series also serves to subvert a dominant paradigm; in this case, the white colonial gaze. In five black and white photographs, the artist shields his face behind masks of (in)famous male colonisers, including Captain James Cook, with his own eyes staring at the viewer through eye-hole cut outs. Presented behind glass in a museum cabinet – an inventive use of the existing gallery architecture – the work challenges traditional presentation of Indigenous culture as historical artefact and forces the viewer to acknowledge their own complicity in Australia’s history. This work takes on further significance in Shepparton, a town named after Sherbourne Sheppard, one of the first European colonisers in the region. Before European settlement the area was home to the Yorta Yorta, and still has a large Indigenous community (the second largest in Victoria, after Melbourne).

In the next room, Yuki Kihara’s Culture for Sale (2014) and Frédéric Nauczyciel’s A Baroque Ball (Shade) (2014) both consciously position the viewer as audience being performed to by the exotic ‘other’. Nauczyciel’s video depicts a dance-off in the iconic drag ballroom style known as voguing, which evolved in African American and Latino LGBTIQ communities in the 1960’s Harlem, New York, ballroom scene. A practise of celebrating strength and forming community by a group that has been traditionally marginalised, it was co-opted and brought to mainstream consciousness by Madonna in her pop song Vogue (1990) and by another white woman, Jennie Livingston, in her film Paris is Burning (1991). In A Baroque Ball (Shade) the dancers primp and pose, performing for an unseen camera positioned where the viewer sits, comfortable on large beanbags. As a cis, white, heterosexual woman, it is obvious that the queer and trans ballroom scene is not meant for me.

Yuki Kihara takes this idea further by requiring the viewer to literally pay to have the dancers perform. Five screens are mounted on the wall, each with a set of headphones and a coin slot next to it. On each screen is a different dancer in traditional Sāmoan ceremonial dress who is ‘paused’ with the words ‘INSERT 20c TO WATCH ME DANCE’ appearing on the screen below. When you insert the money the dancer comes alive, performing a traditional Sāmoan dance and song. Referencing the European practice of Völkerschauen, in which Indigenous people from around the world were displayed for the amusement and entertainment of European audiences, and also mimicking the format of an arcade or video game, this conscious framing highlights the power play between audience and performer. As I inserted the coins to activate this work, I was aware of a conflicting discomfort at my colonial gaze being made explicit; at the same time, I was enjoying the performance.

Indeed, several of the works in this exhibition require the viewer to press a button, crank a handle, or insert a coin, in order to activate it to perform a function. This sets up an interesting audience engagement dynamic, which was further highlighted by the fact that when I arrived at the museum straight off the earliest train from Melbourne, I was the only visitor in the gallery. It seemed that the artists and artworks were performing just for me.

The label copycat is generally considered an insult, the insinuation being that one is not creative or smart enough to think of their own original idea. But this exhibition embraces the copycat method as a productive and subversive force. That the two works commissioned for the exhibition – Michael Candy’s Synthetic Pollenizer (2017), a robotic flower designed to attract bees which has been installed in nearby canola fields, and Super Critical Mass’ collective choir performance Moving Collected Ambience (2014–) – involve engagement with the local environment and community, demonstrates SAM’s investment in connecting with the people of Shepparton. This is a noble intention and I hope it is successful. However, it was the video works that really engaged me – I could have watched them on repeat for hours – and made the trip to Shepparton worthwhile.

Laura Couttie is a writer, curator and arts administrator based in Melbourne.