To be vandal is to damage what you are supposed to revere, to bring to an end what you are supposed to reproduce. If talking about sexism and racism damages institutions, we need to damage institutions. – Sara Ahmed1

Dismantling forms of oppression, for instance, involves a certain way of destroying what has been built badly, built in ways that are consequential in the damage they cause. So to damage a damaging machine in the name of less damage, is that possible? – Judith Butler2

The true damage lies with patriarchy, white supremacy, and settler-colonialism embodied by the statue. It is these forms of oppression that must be damaged again and again … until they are damaged out of existence. – Monument Removal Brigade3

The Miranda Must Go campaign was launched in January 2017. In March 2017, I visited Hanging Rock with an ABC film crew who were filming a segment about the campaign for the Australia Wide program.4 I went to the Hanging Rock Café to get a coffee, as I have always done for the last four years while doing research at Hanging Rock. This time, however, I wore a campaign t-shirt that said “I won’t cry ‘Miranda!’ on Hanging Rock”, and as I order I suggest to the café attendant that they could stock them as souvenirs in their shop. She is unamused. She tells me Picnic at Hanging Rock is a nostalgic story from her childhood growing up in the Macedon Ranges. They used to climb the rock as children and cry out for “Miranda!”. The conversation gets a little hostile and I wonder if she is going to refuse to serve me. Her colleague steps in and tells me that everyone wants to know more about the Aboriginal history but “they” – the traditional owners – are unforthcoming with information. I argue that it is possible that the traditional owners are reticent to share information with us – white settlers – because of the damage and appropriation we continue to perpetrate on their culture while failing to acknowledge the destructive colonial history that dispossessed them. The colleague concedes that a local historian thinks a massacre may have happened in the region, but she says it dispassionately, conveying the information without the same vividness or feeling used to describe her attachment to Picnic at Hanging Rock.

It strikes me that without official markers or ritualised remembrances to that tragic history it remains abstract and remote. There is a problem with the structures of feeling that are given precedence at Hanging Rock.

In recent years, significant contestations of the histories and values promoted by the symbols and iconography given prominence in public space have been fomented by anti-racist and decolonising movements prompting countless monuments to be debated and re-viewed. Forceful contestations of selective colonial, imperialist and whitewashed pasts many statues represent have resulted in monuments being defaced, obscured, and carted away. Statues have become a critical locus for drawing out a discussion about overlooked racial violence and institutionalised racism; a physical site to interrogate the contradictions in the way national histories and collective memory are constructed.

In Australia, however, official feeling regarding whether public symbols honoring white settler histories and conquest need to be reconsidered are mired in conservative sentiment and jingoism. When the Captain James Cook statue in Sydney’s Hyde Park was scrawled with the words “No Pride in Genocide” last year, our Prime Minister described it as a “Stalinist exercise of trying to wipe out or obliterate or blank out parts of our history”.5 The Daily Telegraph described calls to review statues to “our founding fathers” as “Aussie Taliban: PC vandals’ bid to tear down our history”.6 The federal government reacted by moving to put a number of statues of Captain Cook on the National Heritage List, which would make their defacement punishable by large fines and a seven-year jail term.7 In recent weeks, the government has ramped up their commitment to preserve Australia’s distorted, denialist approach to colonial history by allocating millions of dollars to a new statue celebrating Captain Cook in Botany Bay.8 Rather than questioning, recontextualising or removing our colonial monuments, Australia appears determined to reproduce and reinforce them.

All the fearmongering that disputing the narratives perpetuated by colonial monuments is tantamount to historical erasure and vandalism, conveniently evades the fact that reviewing and rejecting outmoded narratives “is itself an act of choice and agency in history”.9 Theorists have noted, for example, that while topplings of Saddam Hussein statues or the prohibition of Nazi iconography in postwar Germany are celebrated in the West, and never equated to Stalinist Purges or Islamic State’s destruction of Palmyra, campaigns to contest colonial statues often do.10 The different reception of such topplings demonstrates, as Rahul Roa argues, that “you are not obliged to live with the statues of your oppressor when Power agrees that he is a Bad Man”.11

What we can conclude from this is that statues and symbols that dominate our public sphere matter greatly, and changes in public symbolism – what is considered dismantle-able? who or what is beyond the moral pale? – matters deeply too. Reducing calls to tear down racist statues as acts of erasure and vandalism is telling also, relegating the intolerable and traumatic nature of problematic statues and symbols, and the damaging, partial narratives they reinforce, as erroneous or inconsequential. As Roa has suggested: “given a context of centuries of oppression and radically unequal contemporary power relations, it behoves us to ask who needs statues and who does not? Who occupies space to the exclusion of whom?”^12

**

In Australia, our monumental racism manifests in insidious forms that can be less overt, but just as damaging, than the celebration and commemoration of murderous pioneers, imperialists, oppressors and Bad Men. The iconic Hanging Rock, a unique geological feature located just outside Melbourne is one such example, where a fiction of white disappearance is repetitively remembered and reproduced while the colonial attempt to eliminate the region’s Aboriginal people that actually took place is downplayed and ignored.

Hanging Rock is most commonly associated with Joan Lindsay’s celebrated novel, Picnic at Hanging Rock, along with Peter Weir’s renowned 1975 film adaptation that popularised the story internationally, which tells a tale of the inexplicable disappearance of a group of schoolgirls and their teacher at the site in 1900. Lindsay’s story completely dominates visitors’ associations at Hanging Rock and enjoys monumental status in the Australian collective imaginary.

Picnic at Hanging Rock was written with deliberate ambiguity about its truth status and while the story of lost schoolgirls has subsequently been found to have no basis in real events at Hanging Rock, many people continue to believe the story describes a factual incident.13 Mimicking a famous scene in Peter Weir’s film adaptation, it is a habitual custom for visitors to cry out for “Miranda”, the story’s most renowned missing schoolgirl, at the rock.

The local Macedon Ranges Shire Council capitalises on the site’s association with the enigmatic myth, and reinforces its construction, by branding tourist pamphlets and road signs with the slogan “Experience the Mystery” and dedicating much space to Picnic at Hanging Rock in the interpretive “Discovery Centre” at the foot of Hanging Rock. The interpretation maintains the ambiguity over the story’s truth-status by giving no clear indication that it is fabrication and using historical photographs to illustrate information panels.

The story of vanishing women is also continually celebrated at the site itself, and across Australia, the schoolgirls’ absence made obsessively present through habitual retelling and reaffirmations of the myth. These take the form of annual outdoor screenings of Peter Weir’s film at Hanging Rock,14 a 2018 “dance flash mob” encouraging fans to dress up as the fictional Miranda,15 a recent celebrated encore run of Tom Wright’s play adaptation at Melbourne’s Malthouse Theatre16 and a new television miniseries filmed on site at Hanging Rock. 17

Paradoxically, the national preoccupation with fictional schoolgirls’ disappearances directs attention away from other more troubling losses that actually occurred at Hanging Rock. What is effectively ignored is the history of dispossession and violent colonial occupation that has resulted in the severe disruption to 36000+ years of continuous Aboriginal presence, cultural knowledge and practice at Hanging Rock.18 Aboriginal producer Jason Timaru writing about Hanging Rock from the perspective of the Dja Dja Wurrung, Yung Balug people of the region, explains:

The truth is my people were hit hard during the frontier wars. The Western region is known to us as the Killing Fields. […] Long before the 1967 novel, 1975 film and the naming of Hanging Rock, Tribes of the Dja Dja Wurrung, Woi Wurrung and Taungurung would gather at that location for important Men’s Ceremony. This is a place where big business was held: Corrobborees, Initiation Ceremonies, Songline Ceremonies, trade and relationship building and a place where laws were made and passed.19

Stephanie Skidmore and Ian D. Clark in their case study of tourism at Hanging Rock have noted that “Indigenous information about the rock’s use in pre-European times is sparse”.20 Few rigourous local histories exist of the Hanging Rock region that draw on Aboriginal oral testimony and colonial records to describe Aboriginal life prior to colonisation as well as what happened to the three Aboriginal groups that held ceremony there – the Wurundjeri, Taungurong and Djadja Wurrung – when European’s occupied. It is an area that remains under researched, documented and resourced. Ironically, this is in stark contrast to the routine research and investigation that has been dedicated to verifying if Picnic at Hanging Rock is based in fact.

We do know, however, that the colonial occupation of South-Eastern Australia was a cataclysmic disaster for Aboriginal people. James Boyce has noted that the illegal squatter occupation of Melbourne in 1835 catalyzed “momentous change in settlement policy”, that saw “settlement no longer restricted to defined boundaries” and “colonisation degenerate into a frenzied land grab”.21 Patrick Wolfe describes how following the founding of Melbourne, “colonists set about removing Native people from their rich Victorian grasslands with unparalleled speed and ruthlessness”, and as a result, Aboriginal people in Victoria “suffered a demographic collapse”.22 Referring to official colonial figures that show Victoria’s Aboriginal population fell from an estimated 12,000 people in 1835 to 806 people 25 years later, Wolfe describes this little acknowledged catastrophe as “far and away the largest fact in Victoria’s history, one that dwarfs the campaign for the eight-hour day, the career of Ned Kelly, the holding of the first Australian federal parliaments or the staging of the Melbourne Olympics”.^23

It is evident the histories that elaborate Victoria’s “largest fact”, the damaging, deadly impact of European settlement and its present consequences, continue to be disregarded and overlooked in public presentations of history. In 1968 anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner dubbed the failure of official histories to substantively address the violence, invasion, massacres and dispossession that marked the Australian frontier, as well as Aboriginal people’s resistance to colonial occupation, as “the Great Australian Silence”.24 Historian Stephen Turner has argued that forgetting foundationally structures settler societies, where the “will to forget is stronger than the wish to know”.25

The consequence of this willful silence and forgetfulness is that a site like Hanging Rock dedicates more interpretation and commemorative activity to the fictional disappearance of white schoolgirls, while a difficult history of violent land occupation and Aboriginal dispossession receives little attention.

**

Relevant to contestations of dominant settler narratives in Australian public culture is theorist Elspeth Tilley’s analysis of what she calls the “white vanishing myth”. Tilley argues that the persistence and repetition of the “white vanishing” trope “is engaged in a strategy of forgetting and displacing the non-white, and installing itself as a constituent of the dominant national mythology”.26 Tilley describes the white vanishing trope as “toxic”,27 a problematic settler narrative that is instrumental to colonisation, cementing domination over stolen Aboriginal land.28 Literary theorists, such as Joan Kirkby and David Tacey, have described white Australian’s as being alienated, estranged and psychically severed from the landscape, and the girls’ vanishing into the Australian bush in Picnic at Hanging Rock has been theorised as symbolically redemptive – a way of transcending this alienation.29 The girls’ vanishing has been claimed as a “white dreaming”.30

Tilley argues, however, that an interpretive focus on white estrangement and redemption in lost-in-the-bush narratives “distracts from the reality of white intrusion into, and alteration of, Indigenous space”.31 An emphasis on white healing achieved vicariously through metaphors of merging and union with nature, provides a comfortable narrative that, Tilley contends, “enables a forgetting of material debts, inequalities, and outstanding grievances, and deflects awareness from the lack of actual mechanisms for appropriately dealing with unfinished business from colonialism’s legacies”.32 In other words, an underlying settler politics that is anxious about white Australia’s illegitimate claims to land and complicity in the erasure of Aboriginal people is effectively evaded.

**

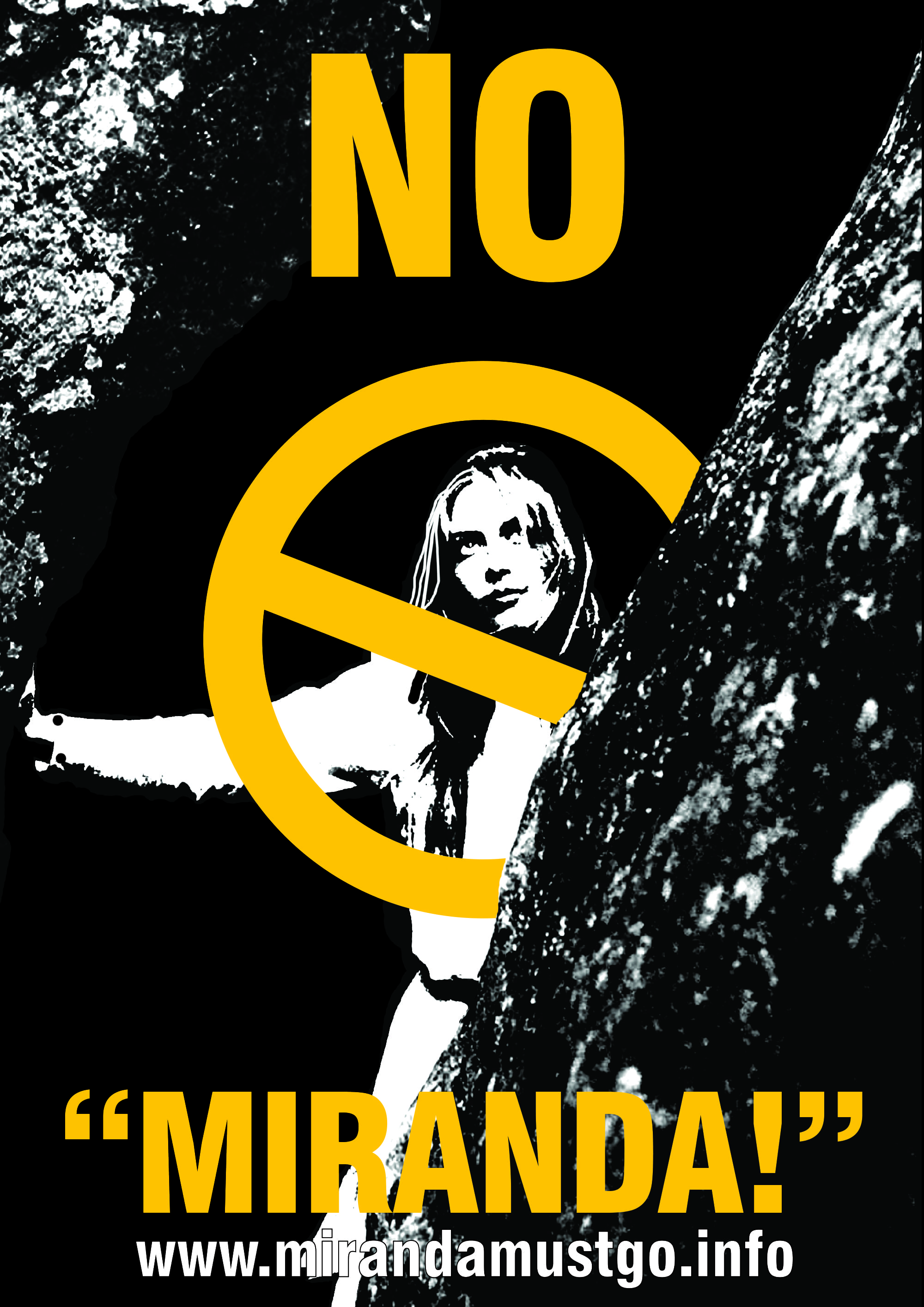

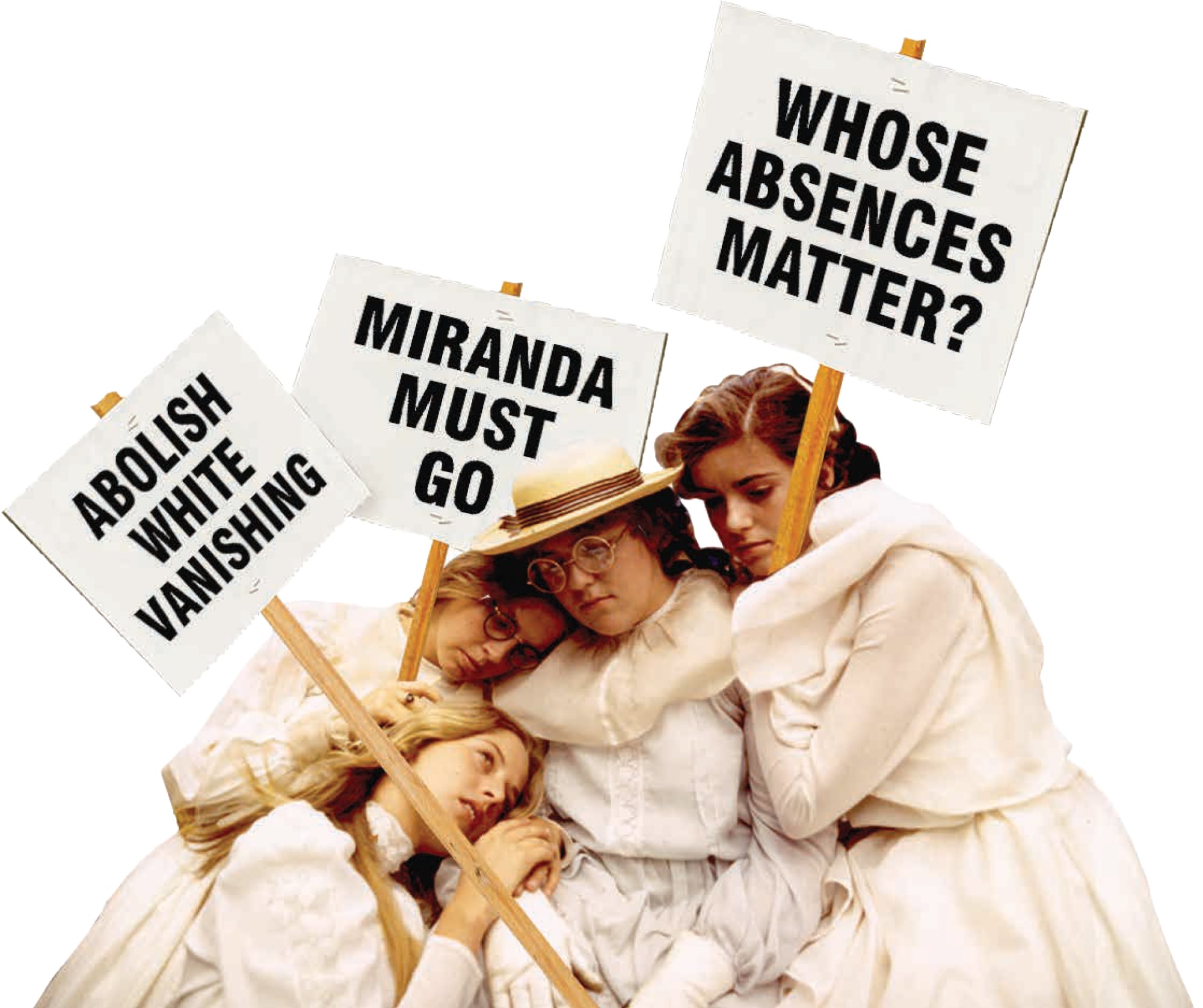

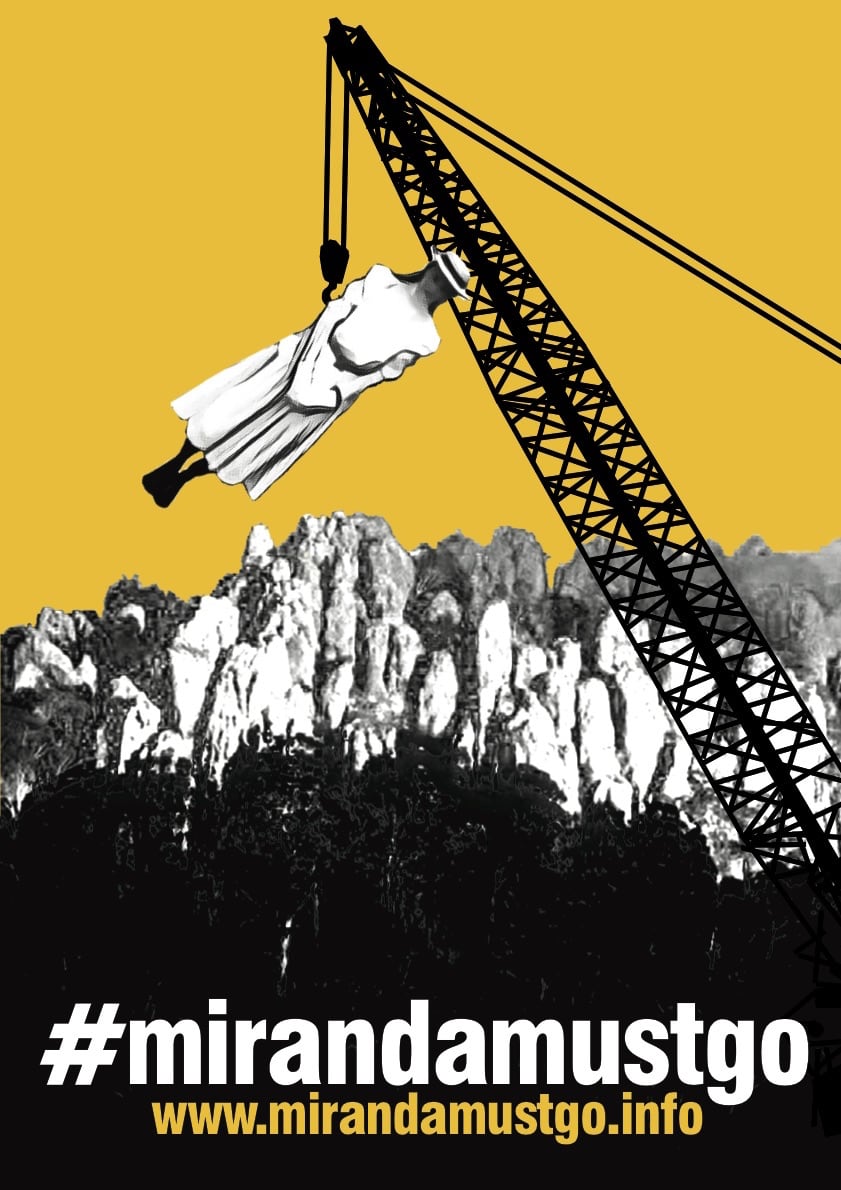

It is evident that in Australian commemorative culture white lives and sufferings, even fictional ones, are more grievable, to borrow a term from Judith Butler, and deemed worthier of remembrance activity, then Aboriginal ones. It was in response to this contradiction that I conceived the “Miranda Must Go” campaign, a conceptual artist’s attempt to discursively deface the monumental presence Picnic at Hanging Rock, and its main character Miranda, occupies at Hanging Rock.

Envisioned as a quixotic, propositional campaign and counter-memorial action, “Miranda Must Go” is a call to settler Australian’s to take responsibility for our entrenched habits of forgetting and silence around colonial destruction that has ensured we know and feel more about fictional white vanishings than actual Aboriginal losses. The intention is to make available to plausible thought the idea that a collective of non-Aboriginal people can come together to dismantle toxic white vanishing myths and demand a confrontation with historical truth. The campaign’s webiste urges non-Aboriginal Australians to learn their difficult place better:

Following its launch, the Miranda Must Go campaign has attracted a lot of media attention and been widely discussed on social media. While many people are reluctant to “erase” the fiction of vanishing schoolgirls there are now frequent admissions that a larger story needs to be told at Hanging Rock that has been too long overlooked. Literary theorists have described the proposal to remove a fictional character from a real site as “ludicrous”,33 while at the same time granting that there is an incongruity in “obsessing over the ghosts of fictional white girls and forgetting the ghosts of real Aboriginal people”.34 Blog posts celebrating the book have conceded the “success of the novel and Peter Weir’s movie overwrote the ‘true history’ of the area around Hanging Rock”.35

Subsequent mentions of Picnic at Hanging Rock have been mindful to acknowledge the traditional owners of Hanging Rock and the site’s “rich and tragic Indigenous history”.36 Artistic Director of Malthouse, Matthew Luton, for example, when pressed about Hanging Rock’s overlooked Aboriginal narratives responded by admitting: “The rock’s indigenous name is Ngannelong, and it’s important that we know that history. I think the Miranda Must Go campaign is a brilliant way to make sure we remember and understand the rock, and that the landscape has a multitude of histories running simultaneously. And you can’t let Lindsay’s story deny the longer and older history”.37

Miranda Must Go’s achievement is that it disrupted the public secret of Hanging Rock’s disregarded Aboriginal significance and violent colonial history. Michael Taussig argues that “public secrets” are certain forms of social knowledge that are generally known but are not publically articulated or acknowledged in order to sustain social powers and institutions – a "knowing what not to know".38 Slavoj Žižek has observed that such forms of public secret can be undermined by publicising them and making a “disturbance […] at the level of appearances”.39 Zizek notes that as a consequence:

we can no longer pretend we don’t know what everyone knows we know. This is the paradox of public space: even if everyone knows an unpleasant fact, saying it in public changes everything.^40

While visitors to Hanging Rock often confess, when pressed, to a niggling anxiety that they know very little about Hanging Rock’s Aboriginal past and cultural significance, this anxiety is often kept private and rarely articulated. Miranda Must Go, however, made this anxiety about missing knowledge a very public feeling in ways that the community can no longer ignore.

Miranda Must Go remains agitating and troubling because it is a speech act that J. L. Austin would call an “unhappy performative”. The campaign does not achieve what it demands. Miranda has not gone, and arguably after the latest slew of adaptations Miranda’s story is more entrenched than ever. For those of us that want Miranda dislodged from her pedestal, for her loss to take less precedence than Aboriginal ones, her continued persistence and reproducibility remains our unsettling problem. As Sara Ahmed notes, anti-racist speech acts in a racist world remain unhappy performatives because “the conditions are not in place that would allow such ‘saying’ to ‘do’ what it ‘says’”.41

Miranda Must Go fails because we remain in a continually colonising and racist scene. It reminds us that there is so much more work to be done to dismantle racist, colonising structures that allow fictional white women to have more claim over our remembrances than real Aboriginal ones. We must be vandals of colonialism’s damaging legacies. We must damage what we are meant to revere and reproduce. We must damage the damaging institutions, monuments, structures again and again until they are damaged out of existence.

Amy Spiers is a Melbourne-based artist and writer who makes participatory and socially-engaged art.