Artist: Del Kathryn Barton

Apparently the National Gallery of Victoria has finally heard the call for fairer gender representation in their institution, because this summer we have been blessed with not one, but four, solo exhibitions by female artists at the NGV Australia in Federation Square.1 It is rather telling however, that running concurrently is a grandiose, solo retrospective of ageing bad boy painter Gareth Sansom, replete with red velvet walls. While Sansom’s show takes pride of place on the ground floor, the female artists have been relegated to the third floor. A further insult has three of the four female artists squeezed into one wing. The final of the female solos, an expansive survey exhibition by Del Kathryn Barton, has been given priority billing, presumably due to her mainstream appeal.

Billed as the “largest ever exhibition of her work to date”, the press release for Barton’s The Highway is a Disco reads like promotion for a Hollywood movie, with phrases including “Two-time Archibald prize-winner”, “never-before-seen” and “one of Australia's most popular artists” thrown about.2 Since Tony Ellwood's appointment to director of the NGV, it seems the institution has continuously priviliged quantity over quality. It leaves me to wonder if and when those with decision making power will realise that bigger does not necessarily mean better.

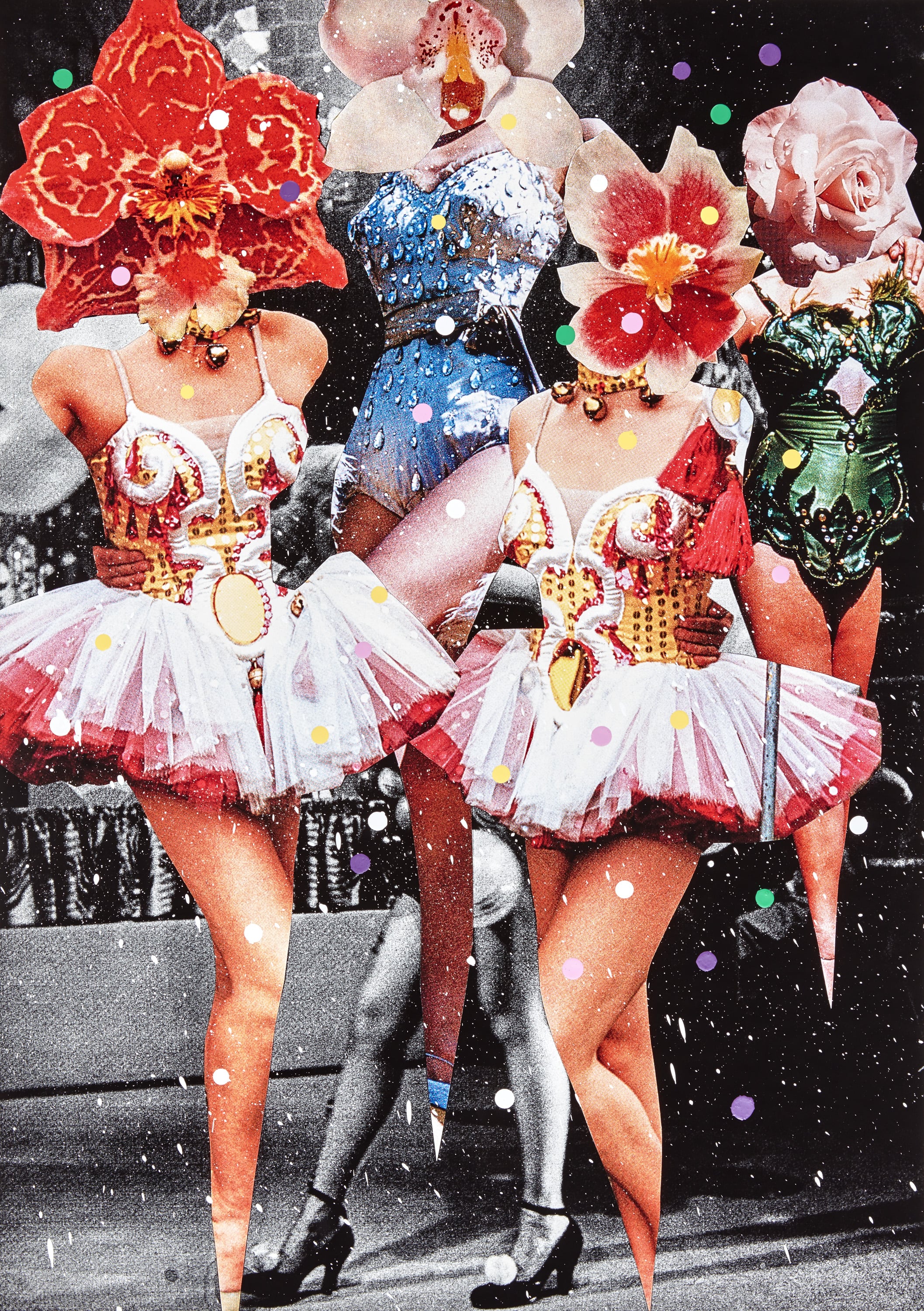

With such an impressive preamble, the exhibition has a lot to live up to. And indeed The Highway is a Disco appears to have it all. In addition to Barton’s trademark vivid, whimsical paintings there are also drawings; towering grids of collages depicting women’s naked bodies and flowers; a room of sculptural penises; an ambitious textile and sculptural installation; a large-scale wall painting; colourful digitally printed wallpapers creating instagram-able backdrops; and a short film starring everyone’s favourite art-film actress Cate Blanchett, with a screaming soundtrack that infiltrates the entire gallery space.

Barton’s quasi-spiritual world is colourful, intricate, and inhabited by mystical animals and feminine dieties. Images of the eye recur across the exhibition, referencing stereotypical superstitious, religious and new age spiritual beliefs involving the third eye, the evil eye or the all seeing eye of God⎯depending which strand of thought you ascribe to. The mother figure appears throughout, both in figurative form and symbolised in the spider and spiders web (as borrowed from Louise Bourgeois). Breasts, vaginal motifs and flowers also recur across the works, iconography that illustrates the notion of woman as nature and woman as generative life force. It is rather a narrow, essentialist reading, given that contemporary discourse is increasingly recognising gender as a social construct, distinct from our physical make up and sexual organs.

The works in the exhibition clearly reflect a deeply personal journey for Barton. The artist herself appears in many of the works, either consciously, as in untitled self-portrait (feeding Arella) (2006), or as the symbolic mother figure. The central installation, at the foot of your love (2017), is a large-scale dedication to her own mother who recently passed away and is, as Barton explains, an attempt to process her grief and channel the emotion into creativity. The family affair continues with the fabric webs in briefly turned into dreams (2016), which were created in collaboration with her mother, and Barton’s daughter Arella also appears as the daughter in the film RED (2016).

With such a breadth of work on display, spanning thirteen years of practice, it certainly seems that there is something for everyone. The exhibition design and presentation are expertly executed, and I’m sure that fans of Barton’s work will delight in this insight into her universe. However, you may not be surprised to hear that I am not one of them. In comparison to The Highway is a Disco, the other three exhibitions at the NGV Australia by female artists ⎯ Helen Maudsley, Louise Paramor and Mel O’Callaghan ⎯ are decidedly more interesting and critically engaged. Maudsley, in particular, is surely deserving of her own retrospective survey after an impressive seventy-year career. And while her paintings are more demanding than Barton’s, upon close inspection and contemplation they offer an endless world of discovery. Sadly, the NGV does a disservice to its audiences by underestimating their engagement and favouring popularity over more complex, challenging work.

Laura Couttie is a writer, curator and arts administrator based in Melbourne.