Artists: Mihyun Kang, Gwan Tung Dorothy Lau, Pixy Liao, Janelle Low, Andy Mullens, Ma Quisha, Sancintya Mohini Simpson, Sad Asian Girls, Zoe Wong.

Curator: Sophia Cai

I have an almost Pavlovian response to the idea of obedience. I was brought up to be filial, to understand that disobedience would be swiftly and severely punished. I saw rebellion as something other people did, something I would never be able to participate in. As I progressed through adolescence and into young adulthood, I became more confident, more willing to break the rules – but I still made sure never to go too far. I never saw disobedient Asian girls or women in the media I consumed, so I didn’t think they could really exist.

And this is why Disobedient Daughters, curated by Sophia Cai, was, for me, akin to a religious experience. Located in Metro Arts’ gallery in the heart of the Brisbane CBD, the heritage-listed building’s wooden floors and vast interior provide a contemplative atmosphere well suited to the task of art consumption, and to this show in particular.

Disobedient Daughters explores the myriad ways in which Asian women can be disobedient. Encompassing the work of nine female artists and collectives, disobedience manifests itself in different forms throughout the exhibition. It dispels the myth that Asian women are a monolith, that we can only be one stereotype or another. It provides a space for Asian women to talk back to the one-dimensional images we so often see reflected back at us in the mainstream media, and to challenge the stereotypes attributed to Asian women in Australian and global contexts.

The periodic clinking of bottles and containers as a woman lies upside down on a bed, slurping and ingesting from a range of high end creams, tonics, and other beauty products, provides the only sound in the space. Ma Qiusha’s Must Be Beauty (2009) leans on the discomfort inherent in watching a woman drinking products not designed for consumption to comment on the internal and external pressure on Asian women to be beautiful, and the obsession with physical beauty in general.

The other video in the exhibition, Sancintya Mohini Simpson’s Loss // Healing (2017), depicting a woman being tattooed, is located in a separate, darkened room near gallery entrance. This seventeen-minute video is mesmerising, the process of ink permanently decorating skin a physical – and permanent – act of disobedience. This is all the more resonant for me as it is an act I am still too scared to do for fear of what my parents will say if they were to find out.

In her photographs I will never pass for a perfect bride or a perfect daughter (2014) and A pendant for balance (2014), Zoe Wong – whose work regularly combines portraiture with other media – plays on the obedient Asian woman trope by subverting images associated with the animated Disney character Mulan. The Mulan imagery is significant in that it symbolises, in part, honour and filial duty. More notably though, for millennial women Mulan was one of the few representations of an Asian woman in popular culture and so, however flawed that representation, she became a touchstone of sorts.

The exoticising of Asian women, an issue that has become increasingly prominent in recent times, is also a major theme through the exhibition. Andy Mullens’ I’m Yours: Lover’s Quarrel (1-30) (2018), thirty photos of supposedly naked women, their bodies painted over with black acrylic paint so only their silhouettes can be seen, comments on the sexualisation of Asian women in Western societies, as does Pixy Liao’s Breakfast (2009).

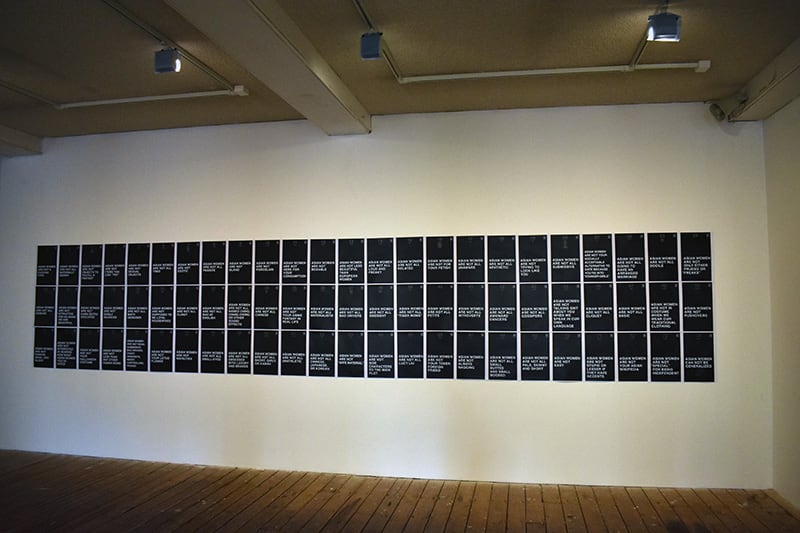

But the piece that had the most impact on me was SAD ASIAN GIRLS’ Asian Women Are Not (2016). A collection of one hundred printed A3 posters, the piece adorns the entire length of a long wall near the front of the exhibition space. Originally ‘a public installation of posters containing statements submitted by the online public, to which we [SAD ASIAN GIRLS] gave the prompt to fill in the blank: "Asian Women Are Not ... ",’ Asian Women Are Not is a visual representation of the internalised frustration and anger that Asian women living in Western contexts, like myself, feel at being constantly and consistently stereotyped. The benign black-and-white colouring of the posters works well to draw attention to the depth of feeling and anger in the statements adorning them.

‘Asian Women Are Not bad drivers’

'Asian Women Are Not your lotus flower’

More than any of the other works in this exhibition Asian Women Are Not made me angry. Angry, because I know what it’s like to have those thoughts, and what it’s like to have to try and dampen my anger because I don’t want to be seen as disruptive, to avoid being stereotyped as ‘that Asian girl who’s causing trouble’.

Michelle Law knows what that’s like, too. In her catalogue essay for the show, Red Hot Anger, she writes:

Nobody wants to be the angry Asian in the room. And my anger isn’t useless; rather, it’s an anger imbued with hope. It mobilises me to keep trying and continue making work that demands equity. Because at the end of the day, the people who will enact change for women of colour is women of colour. We have to be our own champions. We can’t afford not to be angry.

Anger – and for that matter, disobedience – can be a positive force.

As curator Sophia Cai writes, ‘the exhibition does not seek to define what this experience (the ‘Asian female experience’) might be, but instead hopes to offer new perspectives and possibilities for the future’. Disobedient Daughters made me feel seen and understood, and it also gave me plenty of food for thought.

Yen-Rong Wong is a Brisbane-based writer, and the founding editor of Pencilled In, a magazine devoted to publishing and championing the work of Asian Australian writers and artists. In 2017, she was shortlisted for the Deborah Cass Prize, and her work has been published by The Guardian, Overland, Tincture Journal, The Lifted Brow, and more.