Artists: DUDSAPCE with Lou Hubbard, Katie West, Kim Donaldson, Makiko Yamamoto, Sean Dockray & Benjamin Forster, Simone Slee and Yuval Rosinger (Pee Pee and Poo Poo Gallery)

In the exhibition Dissident Assemblies KINGS Artist-Run have taken a self-reflexive approach to celebrate the fifteenth year of the organisation, inviting artists to ‘work within and respond to the parameters of the gallery’.1 The result is a selection of site and context specific projects that variously address the processes and architecture of KINGS, exposing something of its behind-the-scenes infrastructure, historical traces and artist networks.

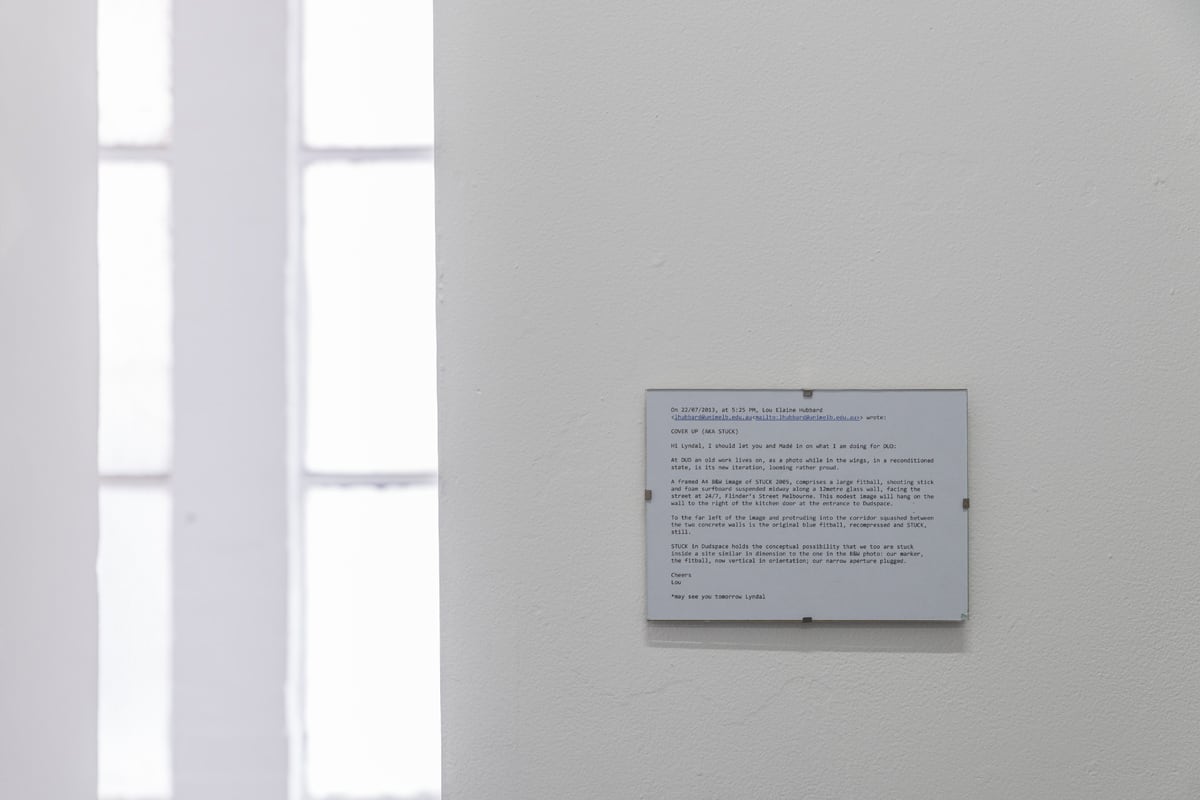

In one instance of historical echo, Lou Hubbard installed a video work and plaque in the gallery’s constricted back passageway formerly known as DUDSPACE.2 Stuck in DUDSPACE STILL (2018) documents and reprises the artist’s Stuck in DUDSPACE (2013) which involved a large round fitness ball wedged between the walls of the narrow corridor leading to the gallery’s toilet. The bright blue rubber ball, squeezing itself into this preposterous exhibition space and clearly outsized for its surroundings, is captivatingly awkward and appears on the verge of bursting. The video reprisal, shown on a flat screen television in the same space, leads us into this rabbit warren cul-de-sac behind the back gallery. To me, in the context of this exhibition (viewed after passing through the pseudo office of Yuval Rosinger’s Poo Poo and Pee Pee Gallery with their elaborately bureaucratic exhibition application forms), Hubbard’s work speaks to the contortions that artistic practice might go through in order to be seen.

The impetus behind many ARIs (artist-run initiatives) since the 1990s and 2000s has been to provide artists with exhibition opportunities that afford a high degree of control over the contextualising of their work. Clearly a response to the scarcity of exhibition opportunities relative to the number of practicing artists, this may also be seen as a reaction to the authorial role of curatorial work in institutions and exhibition making. Spaces such as KINGS seem to take a more horizontal or committee-driven approach to programming, spreading and sharing decisions rather than foregrounding any singular voice in shaping their artistic direction.3

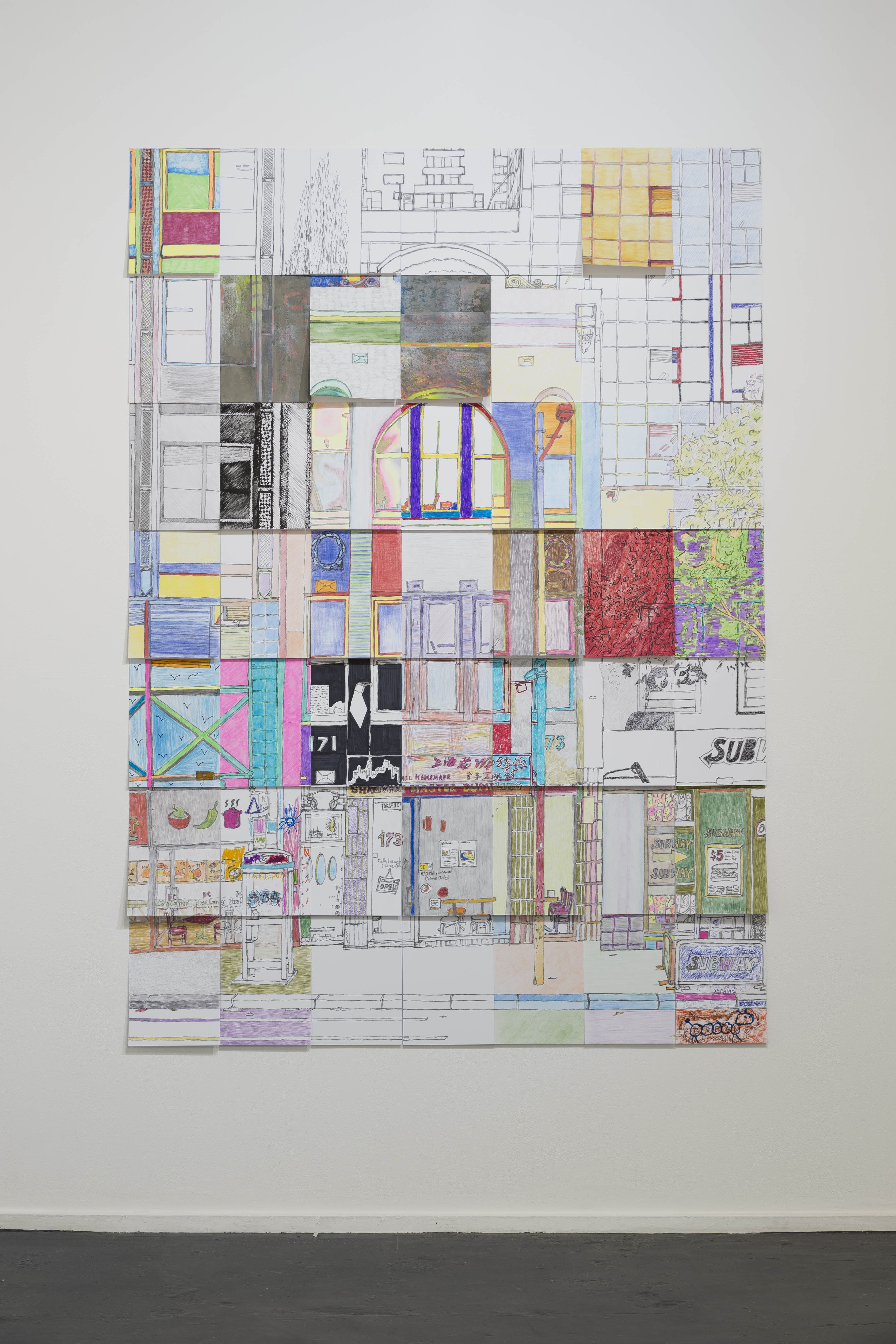

This unmediated or ‘un-curated’ approach to generating and presenting exhibitions is carried through several works in Dissident Assemblies that perform collaboration as a process of deferral or out-sourcing. Kim Donaldson called on a number of artists associated with KINGS to interpret and complete her work More than the sum of its parts (2018). Donaldson’s drawing of the gallery has been scaled up and divided into a grid which was dispersed among other artists to colour and finish. When pieced back together the work became a fragmented portrait of the space seen from multiple perspectives over time.

The aforementioned Poo Poo and Pee Pee Gallery invited visitors to the exhibition opening night to apply to exhibit and make work for the ‘gallery’ installed in the toilet at the top of three long flights of stairs. This work, officiated by collaborating artists in the role of ‘technicians’, was Dissident Assemblies most obvious parody of the ARI model – with its exaggerations of hasty timelines, make-do materials, barely accessible space, and overbearing bureaucracies. The (accidental?) toilet theme continued in the exhibition through Makiko Yamamoto’s work A song for bladder (2018), performed by collaborators at the exhibition opening.

Artists Sean Dockray and Benjamin Forster created an online peer-to-peer library built from the personal download folders of KINGS committee members. Constructed on the app Samiz-Dat, files are both pulled from users’ libraries and then collectively hosted by those users, in this case the KINGS committee. The library is then accessible to anyone who installs the app and logs in with the key code available via the KINGS exhibition. Creating a ‘library of libraries’, the app clearly references the Eastern bloc underground publishing network Samizdat which sought to evade Soviet censorship by circulating bootleg copies of contraband literature. While the app is a powerful means of sharing knowledge and work, the dissident history of its namesake is a little off-kilter with the banality of the less-than-dangerous collected files shared through the KINGS library. Those persistent enough to install the work will find a changing collection of decontextualised attachments and files, a form that somewhat mirrors the dispersed and remote working methods of an ARI committee.

Katie West’s One Square Meter (2018) is perhaps the only work in the exhibition that takes a deep view of history, locating KINGS within its geographic and colonial heritage by bringing plants endemic to Naarm into the gallery space. It’s a solitary voice within an exhibition that otherwise seems to revel in its self-referentiality and fifteen-year history. The catalogue accompanying the exhibition explains that Dissident Assemblies aimed to look to KINGS’ future as much as its past, and I’d hope that West’s voice might not seem so isolated moving forward.

Rocks happy to help #20 (2018) by Simone Slee echoes the wedged awkwardness of Lou Hubbard’s blue fitball, with a blown glass form held between two rocks and set upon a thin, flimsy-looking support structure. Slee’s work can be seen in this context as a beautiful metaphor for the precarity and malleability of ARIs. When hot and fluid the glass finds its way and takes shape, it binds together the rocks, protruding and claiming space where it can. Together, the whole balances miraculously on a seemingly unstable platform. But once it sets, the glass bubble becomes fragile rather than flexible and fluid, held still in that moment of expansion, visually tracing its liquid origins.

Narrm/Melbourne-based curator and arts writers Rosemary Forde has developed exhibitions and events at a range of institutions and contemporary art spaces in Australia and New Zealand. She is currently a PhD candidate in Curatorial Practice at Monash Art Design & Architecture (MADA), Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.