Artists: Raj Kumar, Sonia Leber & David Chesworth and Adeela Sulamen.

Curators: Mikala Tai and Kate Warren.

I don’t want to be there when it happens takes its title from a work by Adeela Sulamen, and forms a statement of intent for this exhibition at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art. The exhibition features the work of Pakistan-based artists Adeela Sulaman and Raj Kumar, and the collaborative work of Melbourne-based artists Sonia Leber and David Chesworth, with the objective of bearing witness to and exploring the traumatic effects of war while memorialising lives lost in conflict in Pakistan. The exhibition provokes us to think about the daily uncertainty and horror of life in a war zone from the privileged and comfortable position we occupy in Australia.

The ground floor galleries hold two large-scale sculptural works by Adeela Sulamen. Sulamen was born and is based in Karachi, the largest city in Pakistan. Karachi residents have experienced religious and politically-based violence for many years, exacerbated more recently with the rise in power of the Taliban. Sulamen’s work is testament to a life lived in this conflict zone. I don’t want to be there when it happens (2013-17) is a large, elaborate chandelier created from hundreds of interlinked, hand-beaten steel sparrows rendered with careful detail, the light radiating shadows onto the gallery walls. Moving further into the space, you encounter Sulamen’s After all it’s always somebody else who dies (2017) descending the gallery stairwell. Also composed of interlinked steel sparrows, in this work the sparrows’ feet and beaks touch, creating a shadow like a cocked pistol on the wall behind. The shadow play in both works serves to mirror the darker, ungraspable forces involved in the daily violence unfolding in Karachi. The symbol of the steel sparrows is equally pertinent. As part pf her practice, Sulamen began producing a bird for each person killed in her hometown but very quickly there were too many deaths to keep up with. Her work forms a kind of cenotaph to these people.

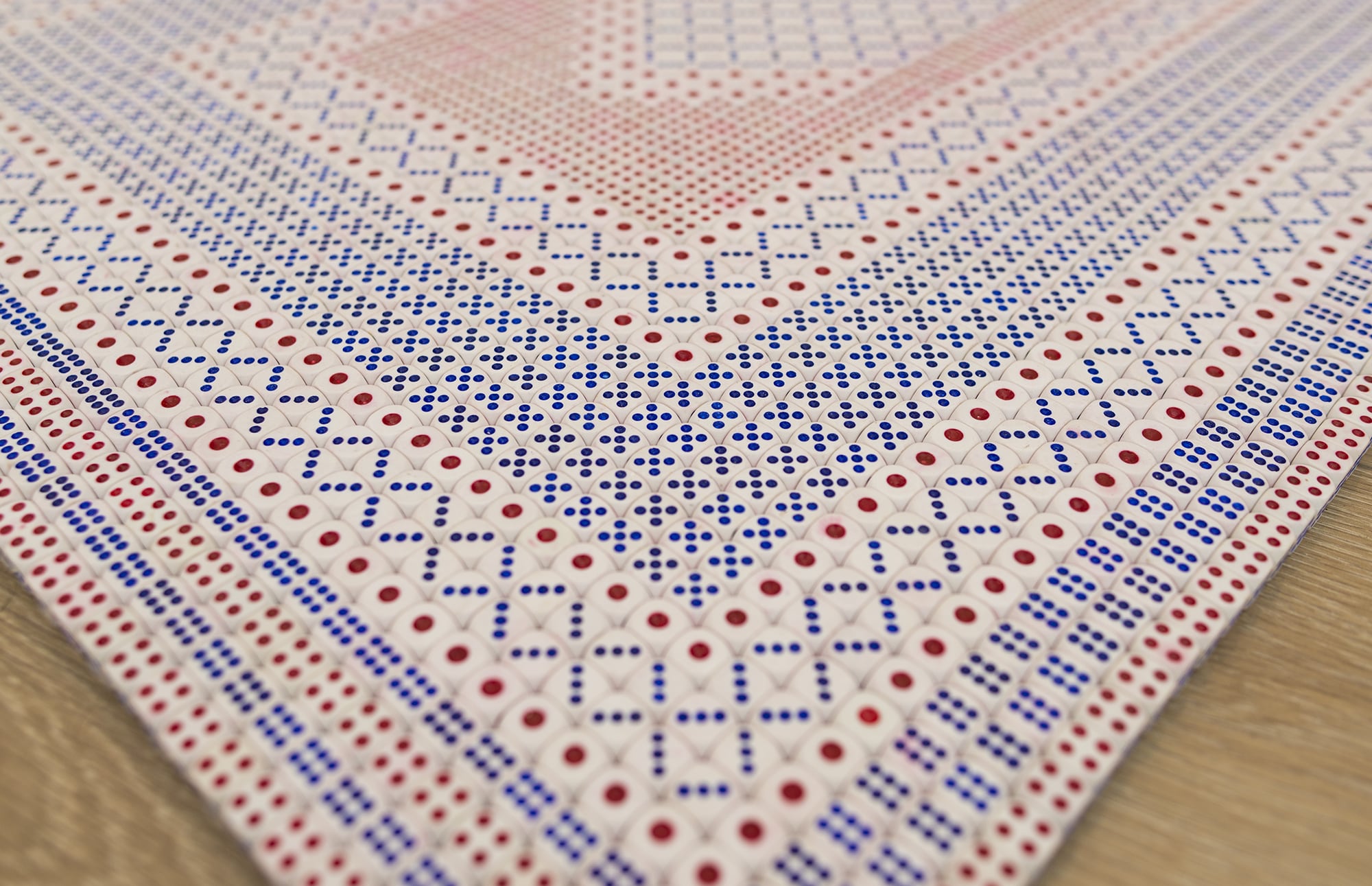

Emerging Pakistani artist Raj Kumar’s Meet, Pray and Pay (2017) comprises carefully positioned hand-woven prayer mats that point towards Mecca. Although Islam has been the official religion of Pakistan since the early 1970s, religious conflict has been at the centre of the violence and divisions that are currently an everyday part of contemporary Pakistani life. With each of the prayer mats woven from individual dice into impressive geometric patterns, Kumar uses this symbol of chance as metaphor for the dangerous and precarious nature of religious belief and affiliation in Pakistan.

Leber and Chesworth’s eerie video Earthwork (2016) confronts surveillance and the use of drones in warfare, casting a detached and dehumanising bird’s-eye view over the landscape. Panning over a damaged and destructed model suburban scene, the video is disorientating and disempowering as this bird’s-eye view becomes the God’s-eye view, as engineered by the artists. The work’s placement on the floor emphasises this perspective, forming an act of part documentation, part possession of the landscape. The wall text for Earthwork mentions Collateral Murder - the 2007 video of a US-led airstrike on Baghdad - as a point of reference for the artists. The horror of that video is not easily forgotten; living in the moment of ‘alternative facts’, the contrived nature of Leber and Chesworth’s video seems all the more pertinent.

Each work featured in I don’t want to be there when it happens was profuse with complex concepts and emotionally dense material that astutely considers war, surveillance, and the political and religious dimensions of conflict. That said, taken as a whole I found the exhibition a little sparse. The upstairs gallery in particular featured only two works, both positioned on the floor, with the walls left completely bare. The exhibition will be showing at Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts later in 2017 with an additional four artists and collectives unfortunately not involved in the 4A iteration. I wonder how this will change the impact of the exhibition.

I don’t want to be there when it happens makes the important point that in a relatively peaceful and stable society like Australia, we have no real understanding of what being in a war zone feels like. No understanding of what the constant hum of danger, uncertainty and trauma can inflict on a person. The works of Kumar and Sulamen, in particular, expand our understanding with their personal, emotionally-laden insights and sensitivity to the horrors of ongoing violence and war. In doing so, it reiterates how important it is to be vigilant of our rights, of political and social justice, at a time when hatred and violence seem to be everywhere.

Kathleen Linn is a Sydney-based emerging writer and curator.