Artists: Laresa Kosloff, Foster and Berean, Stuart Ringholt and David Rosetzky

Curator: Chelsea Hopper

In recent years, the residency has taken on new and greater proportions as a rite of passage for artists. Next to the biennale, it encapsulates the ripest combination of travel and art, the height of cultural tourism. Of the various residencies available to artists in Australia, Monash’s Prato residency is one of the more enviable offerings. Since 2010 the selected resident is flown to Prato, put up in Monash’s Tuscany base for three months and given a $10,000 expenses allowance. Sounds luxurious.

Yet despite their proliferation, rarely do we see the cumulative fruits of a residency. For In Prato, curator Chelsea Hopper has brought together the works of three artists and one collaborative duo, all of which were produced during Monash’s Prato residency. Laressa Kosloff, Foster and Berean, Stuart Ringholt and David Rosetzky demonstrate varying degrees of engagement with the city of Prato as the backdrop for the works that were exhibited; the exhibition refuses the notion of a hard and fast geographical imprint in the artwork-as-outcome. Not to say that this is a negative quality. In fact, the exhibition does well to halt any preconceptions of what work produced on a residency should look like. Given the increasing globalisation that the world is experiencing, coupled with the accelerated pace of international travel, there is no way an art of ‘pure’ cultural expression is even possible.

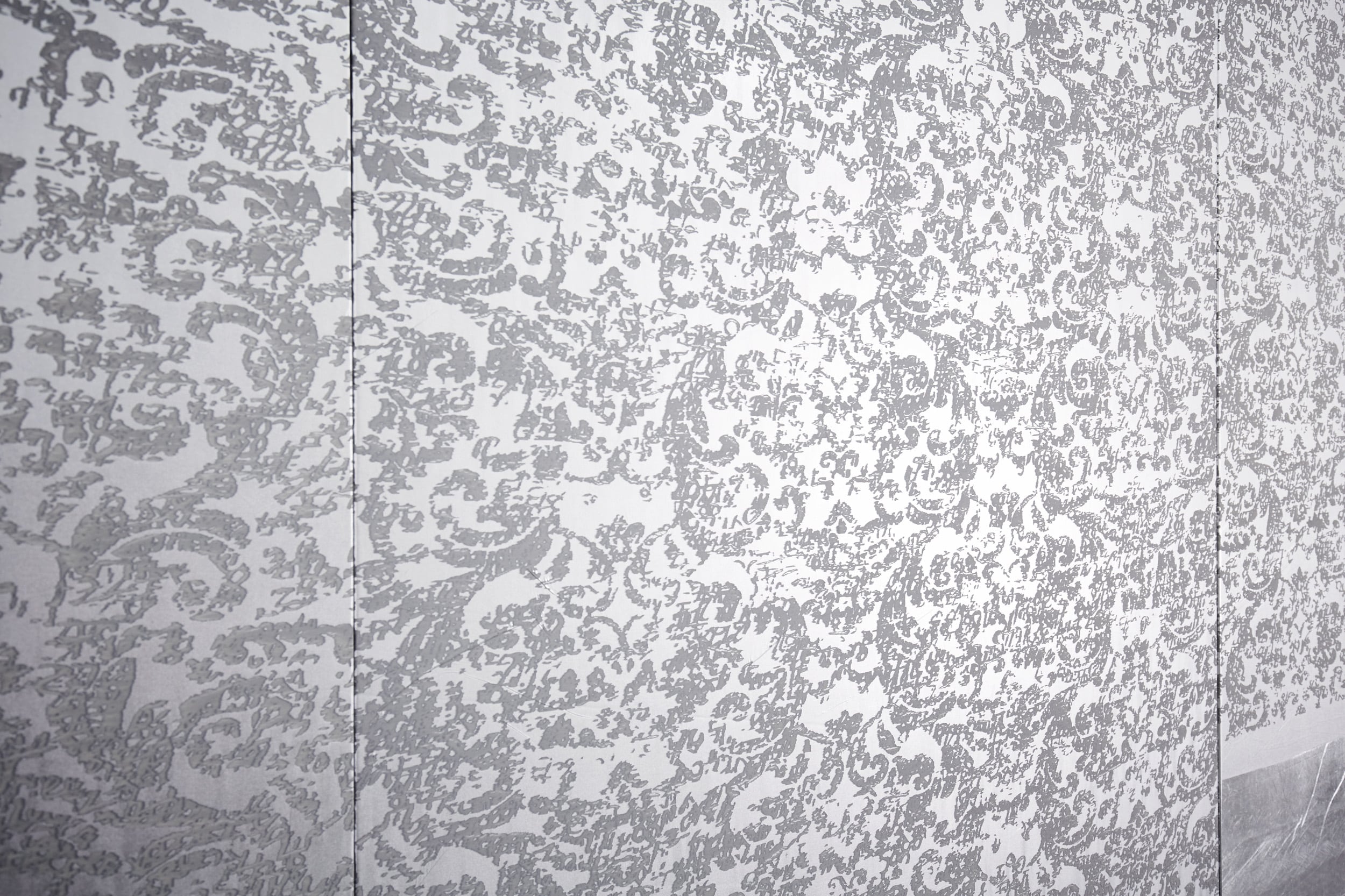

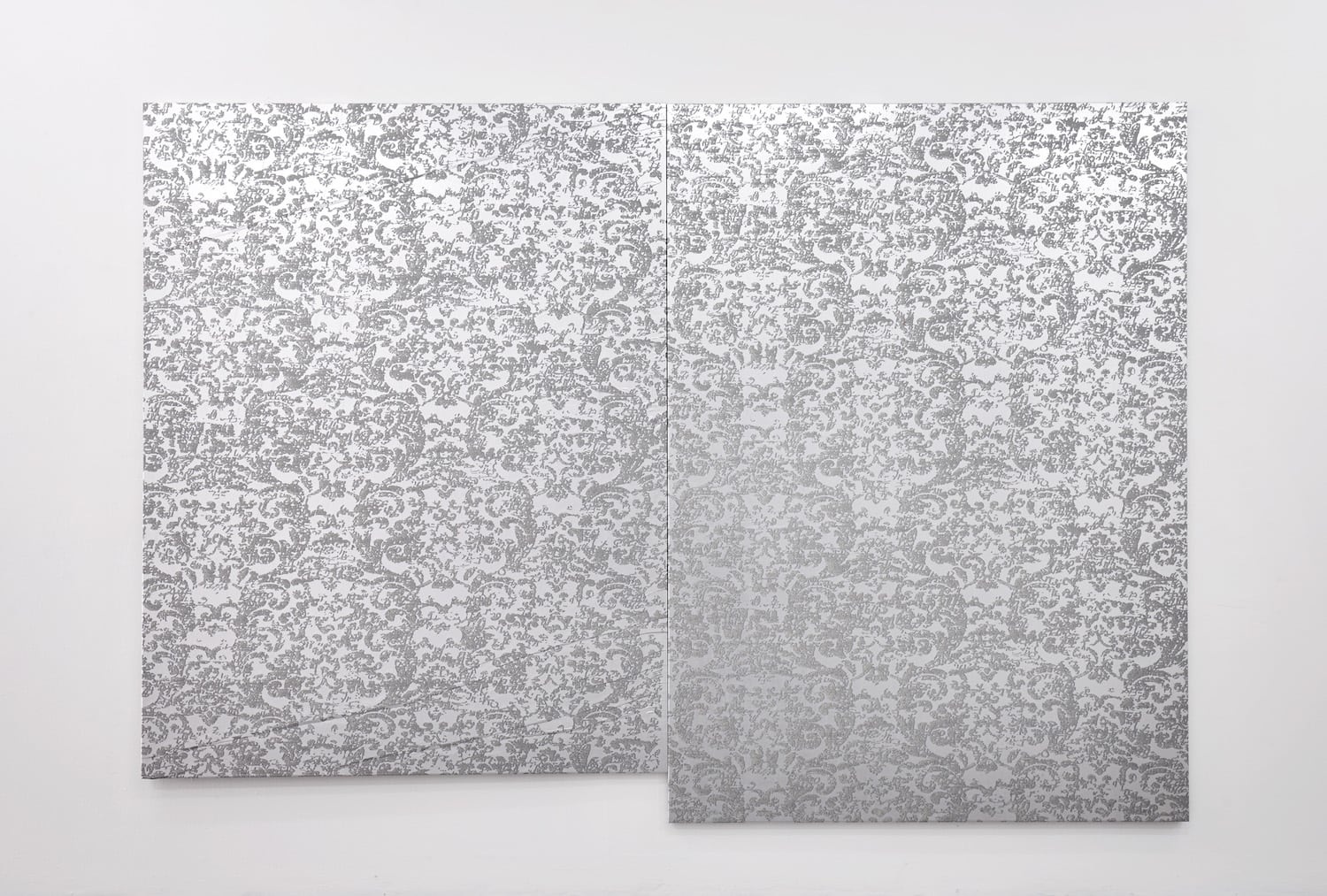

Indeed, one might argue that there is no such thing as ‘Italy’ as it might have once been sold to us. Pat Foster and Jen Berean’s works respond most to Prato as a site and yet simultaneously demonstrate the fallacy of an Italy based on Italian ‘ethnicity.’ During their residency, Foster and Berean discovered the city’s enormous Chinese migrant population, coming across the various walls in the city’s Chinatown scrawled with Mandarin that serve as makeshift noticeboards where immigrants advertise their services in the hopes of finding employment. This is reflected in 377 841 4319 and 377 832 4380 (both 2014), large panels that appear to be covered in textile embossed with a renaissance pattern, a reference to the tradition of textile manufacturing that Prato is famous for. Yet instead of solid prints, the patterns are made up of thousands of phone numbers left on the noticeboard in a nod to the role of immigrant labour which has largely overtaken the manufacture of Prato’s traditional textiles, simultaneously upsetting the ‘authenticity’ of the traditional crafts and exposing the place of immigrant labour in upholding those same traditions.

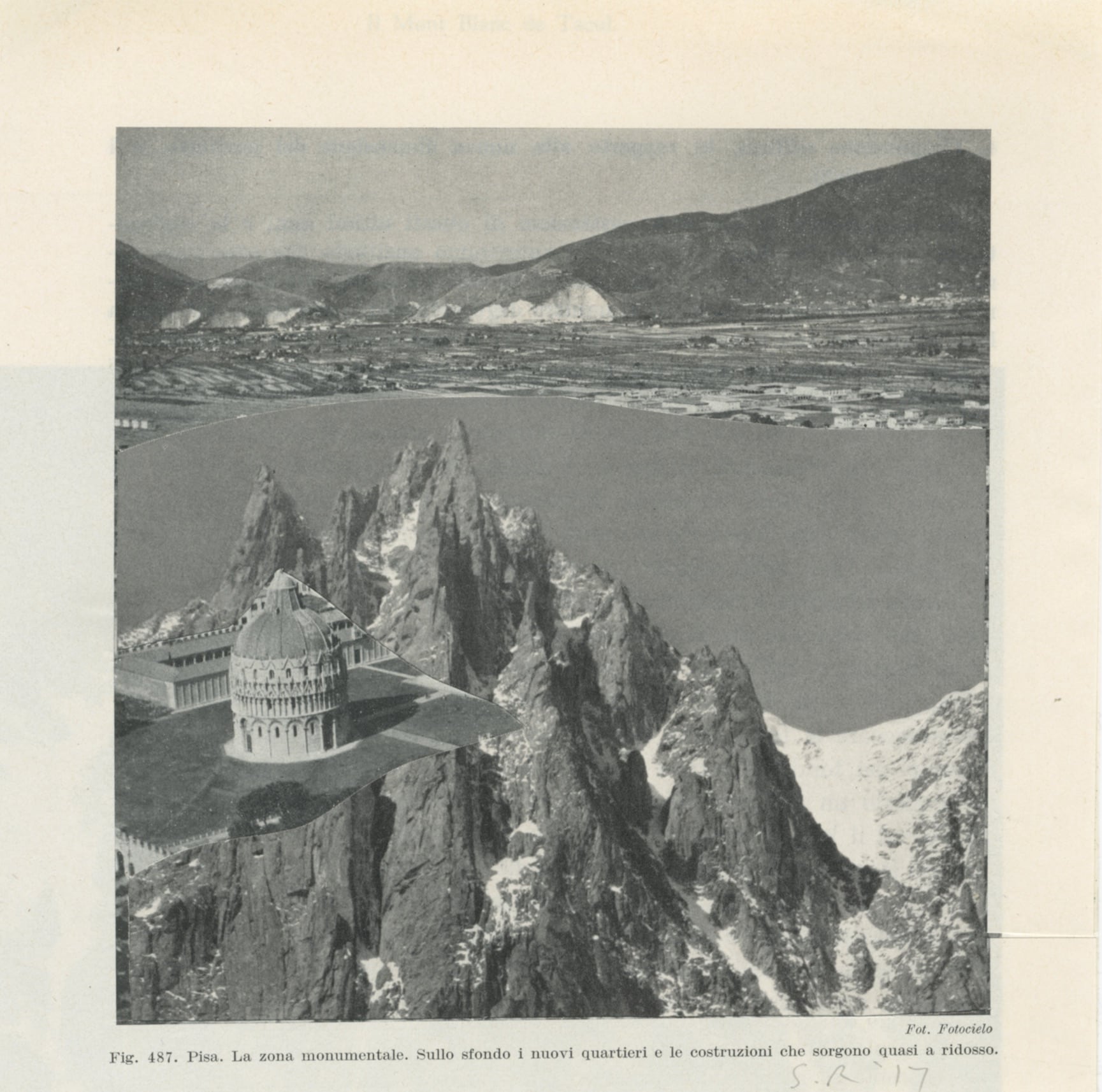

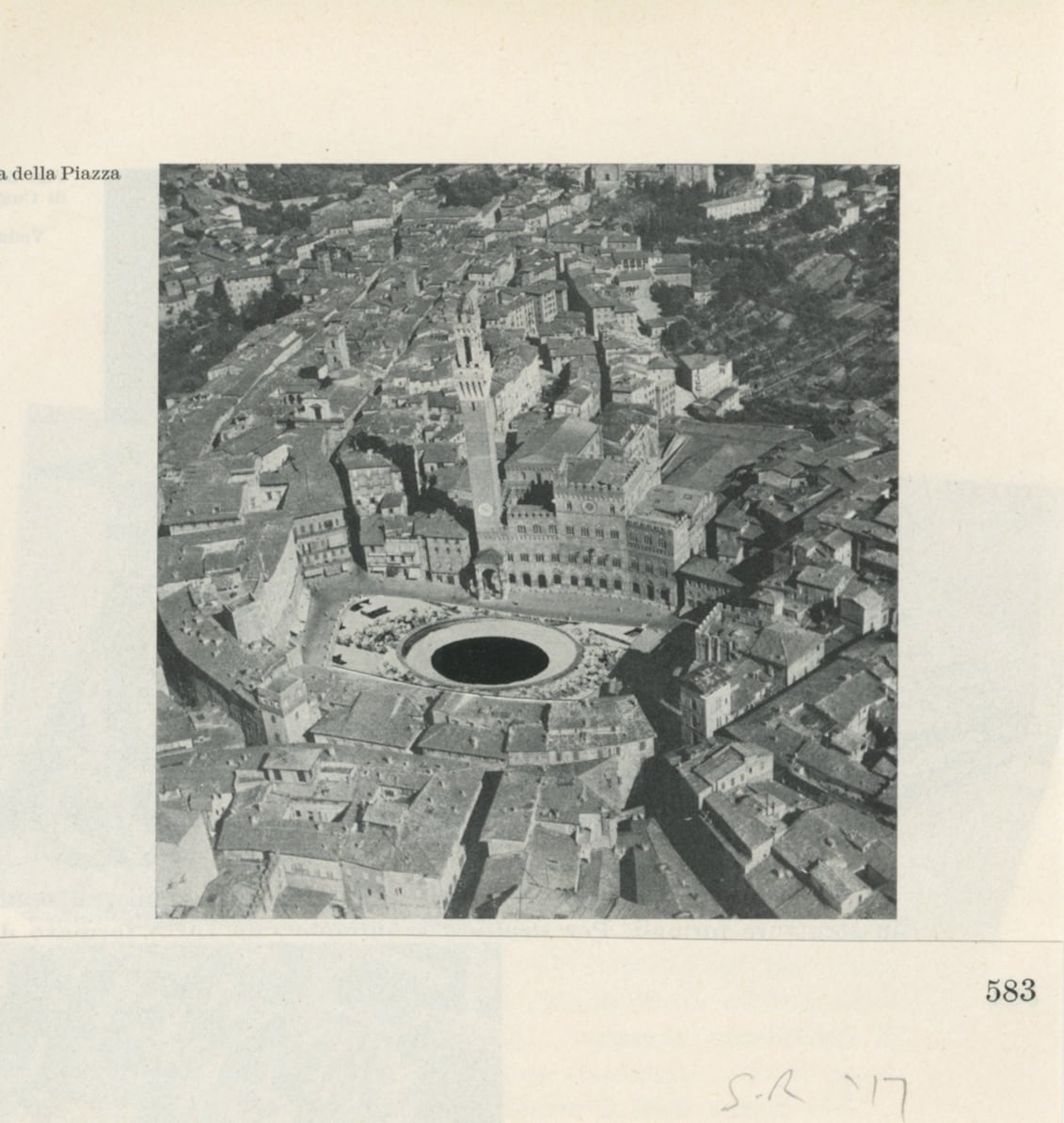

Ironically Foster and Berean’s works, for all their abstract aesthetic, are perhaps the most culturally responsive works in the exhibition. On the other hand, Stuart Ringholt’s beautiful, small collages that depict Italian architecture and landscapes are, according to curator Hopper, not actually about Prato or Italy but more about concepts of time and process. Cut and assembled from second-hand architecture books sourced during the residency, the works juxtapose structures erected by humans with natural landscapes. The uniform tone of the images makes it at times almost impossible to distinguish between what is real and what has been constructed. I can’t help but smirk at the discursive text written by Hopper in the accompanying catalogue where she describes the centre of the depicted piazza in Ringholt’s Page 583 (Piazza Void) (2017) as an ‘arsehole’. But the void could just as easily be a black hole straight out of a science fiction movie. Indeed, Ringholt’s archival collages that depict various times in human history layered on top of each other evoke science fiction. And yet they also evoke the confusion that the continual overlapping and collapsing of time and space have upon us in the present day.

David Rosetzky’s 2 channel video, Incomplete, open (2013-2014) is, in keeping with the artist’s character – exceptionally polished. Better known for his photographic works, maybe Rosetzky is superior as a filmmaker? The video was shot with two static cameras (the footage of each makes up the two channels) and is a sumptuous piece that focuses upon human movement by way of choreography. The dancers perform in the foreground, while a musician in the background performs the soundtrack. One of the most intriguing things about the work is the backing of the two channels onto one another. The effect is, not unlike Ringholt’s works, one of disrupting expectations with subtle juxtapositions. When the viewer goes from watching the ‘front’ screen to watching the ‘back’ channel they expect, by cue of the orientation, to see a mirror image of the first video. Instead, it is almost identical save for the fact that the second channel was filmed with a separate camera and, therefore, alters slightly in orientation. I’m not sure what the significance of this formal gesture is, only to say that it is jarring and surprising when juxtaposed with the flowing movements of the bodies depicted on the screen.

Reflecting in such detail about the works it strikes me that if anything unites them, it is that they all play on the gap between expected and actual outcomes. Whether that was intentional on the part of the curator or the artists is anyone’s guess. But it acts surely as a metaphor for the way in which we approach tasks that have an expected outcome – such as a residency.

Laresa Kosloff’s I Can’t do Anything (2015) is perhaps the height of this thematic. The video depicts people arbitrarily reciting the line ‘I can’t do anything’ (the irony of which is that saying that line is, in fact, doing something), some in Italian, some in English. The notion of productivity is of concern in this video; you go on a residency to produce work, right? But it would seem that, rather than efficiency, Kosloff is more interested in the consumption of time by way of time wasting. A similarly arbitrary use of time is demonstrated in the video Let’s do Something in Italian (2015) that follows a young girl drumming what can only be described as a really awful beat. When Kosloff was on residency, she watched children undertake medieval drumming and flag-throwing classes. Because that’s what you do in Italy, right? In spite of these skill-building activities, Kosloff eventually chose to ask the young girl we see in the video to drum, undoing any sense of expertise. Both videos beautifully encapsulate actions and events that express a certain anxiety about what is anticipated of us and our own time.

Notions of time and productivity are evident not just in Kosloff’s work but across the whole of In Prato. Whether this is a conscious thread is speculative. Though I feel we can say with certainty that in most aspects of existence, even art production, these two interrelated concepts are constantly making themselves known.

Amelia Winata is a writer who has contributed to Art Monthly, Art Guide, Gallery Magazine, Dissect, Memo Review and others.