Artist: Jenny Watson

Curator: Anna Davis

Jenny Watson: The Fabric of Fantasy is a well overdue survey of the work of one of Australia’s most iconic painters, now in her fourth decade of practice. Thoughtfully organised by Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) curator Anna Davis, Jenny Watson’s most comprehensive retrospective to date is currently at Heide Museum of Modern Art in Melbourne following its debut at the MCA in Sydney in July 2017. The MCA exhibition contained over one hundred works, seventy of which have been selected for Heide’s smaller spaces. The experience of seeing both exhibitions is akin to listening to a full album versus a compilation of greatest hits – the latter (Heide) delivers what you know and love, but misses a little of the nuance.

Jenny Watson: The Fabric of Fantasy traverses the artist’s stylistic developments from the 1970s to the present, from her early realist paintings through to the sketchy, ambiguous psychodramas for which she is best known. Though the artist’s style has changed dramatically, Watson’s thematic concerns are abiding – her work has always merged autobiography with fiction.

One of Watson’s earliest paintings, the large-scale Cyclone Fence with Great Dane (1972), features a camel-coloured dog with a lolling tongue viewed in profile. The animal is restrained by a looming field of hurricane fencing and pushed to the very bottom right hand corner of the frame. Here is a creature poised for escape. Continuing this theme, Watson’s House series (1976-1977), created a few years later, depict her various childhood homes in suburban Melbourne painted in a semi-realist style. Each work consists of one smaller and one larger painting of the same house, translated from a photograph using a still-visible grid. As well as reflecting on her past, these works expose the artist’s interest in mark-making (note the seductive daubs of white on white on the periphery of the canvases) that increasingly comes to the fore.

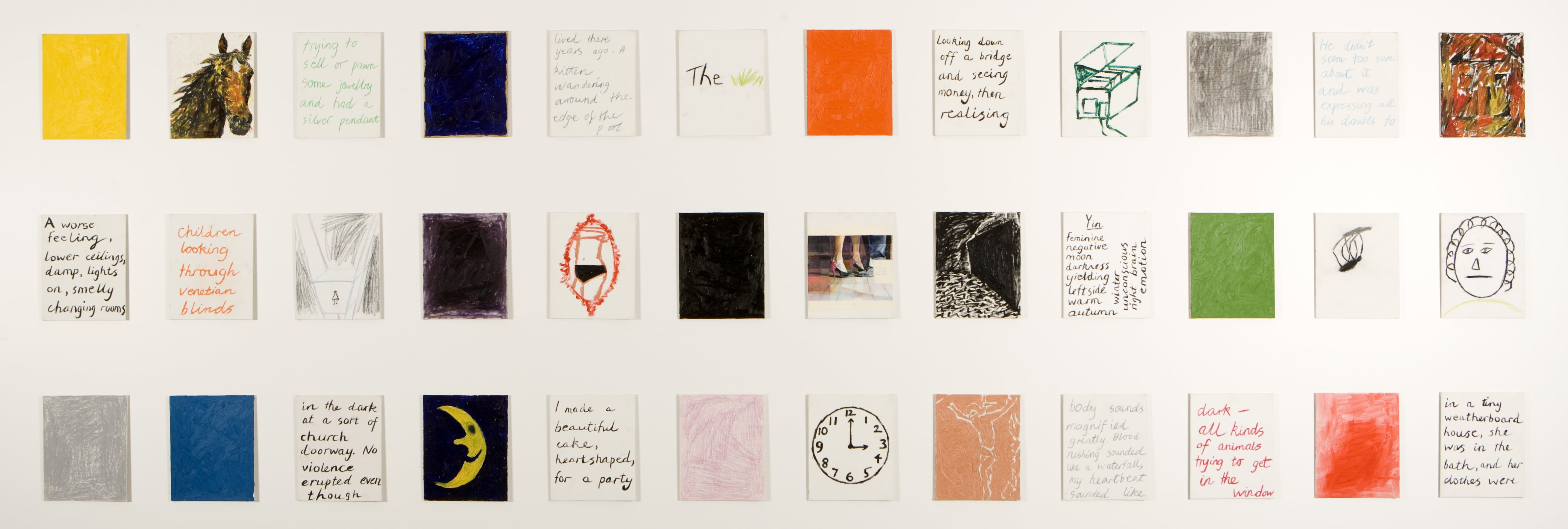

Watson’s immersion in feminist discourse (ignited by her first trip to New York, the centre of the feminist movement in 1975) and particularly feminist readings of psychoanalytic theory had inspired her to mine her own subconscious for content. By the end of the 1970s Watson had shifted from documenting the external world to instead asserting her own personal imagery as a valid form of subject matter. The pivotal work Dream Palette (1981) reflects this transition. It consists of thirty-six small canvas boards containing images and texts derived from the artist’s dream journal. The panels’ disparate content emulates how memories are often recalled in fragments, as we flit from one recollection to the next. Dream Palette also reveals Watson’s move towards a more deliberately expressionistic style.

Watson’s immersion in the 1970s Melbourne punk scene also encouraged her to mess things up a bit. One of the exhibition’s most memorable rooms (in the Sydney incarnation particularly) addresses this period of the artist’s life through a series of large, single panel works created in the 1980s. The Crimean wars: the bar at the Crystal Ballroom (1985) is a monumental painting of a club frequented by Watson and her fellow artists and musicians, like Philip Brophy and Nick Cave. The late-night scene is painted in a shower of rapid, lively strokes that emulate the intensity and energy of punk music.

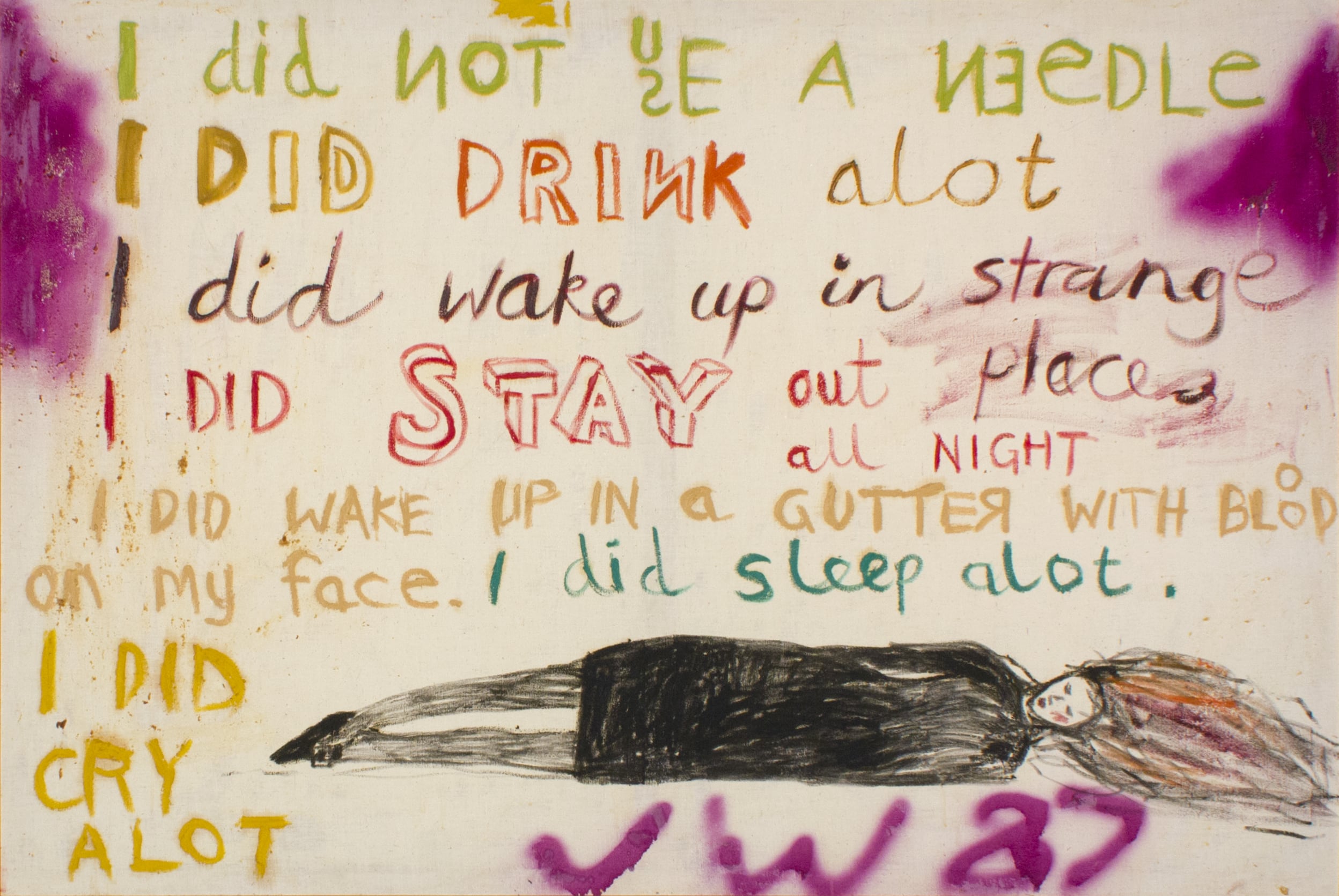

Watson paints the fallout from these nights too. The majority of The Key Painting (1987) is engulfed by text; ‘I did not use a needle, I did drink a lot, I did stay out places all night, I did wake up in a gutter with blood on my face, I did sleep a lot, I did cry a lot’. This confession (accompanied by the image of a prostrate woman in black) resonates. We’ve all been there! A contemporary soundtrack featuring The Easybeats, The Boys Next Door and The Go Betweens accompanies this suite of paintings from the 1980s. All too often these kinds of enhancements are superfluous in an exhibition context but in this instance the presence of music makes sense; it matches the exuberance and vitality found in Watson’s paintings and successfully reflects how different creative disciplines can feed off one another.

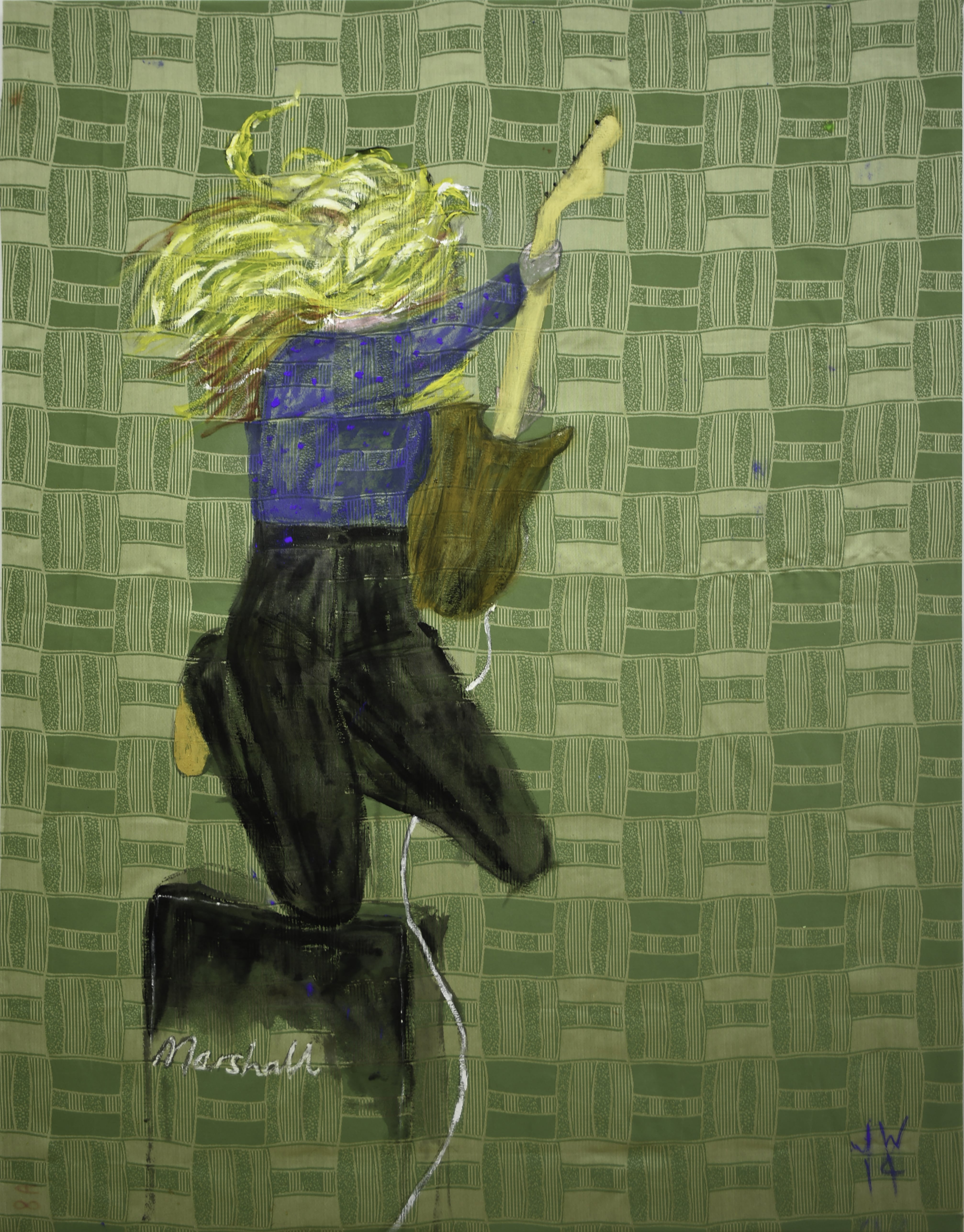

Empowered by the feminist assertion of the validity of female experience as subject matter combined with the transgressive sentiments of punk, Watson’s signature style emerged. The artist’s mature paintings are identified by several key characteristics – roughly sketched figures, often of red-headed women, little girls, horses and cats (all alter-egos of the artist) painted atop patterned textiles, from chaff bags to pretty chiffons, that are sometimes rubbed down with sticky brown chunks of animal glue. These canvases are often accompanied by smaller, floating text panels bearing diaristic observations like ‘woman drying her hair on a wet afternoon’ and ‘I feel like when I used to go and meet J at the gallery’ that can either complement or complicate the imagery presented.

Within the exhibition there’s often an interplay between Watson’s wicked sense of humour - witness the woman on her hands and knees in The Pretty Face of Domesticity (2015) - and quieter moments of contemplation. A highlight is Painting for a man who likes his privacy (1993) in which Watson’s red-haired protagonist appears naked, her back to the audience. Painted in sparing strokes the unidealized female form is relatable to anyone who’s ever stood in front of the mirror, cautiously examining their own reflection.

The simplicity and frankness of Watson’s revelations (matched with her immediate, pared-back style) is what makes her work so disarming. Jenny Watson: The Fabric of Fantasy reveals an artist resolute in the strength of her visual language, using her sketchy, ambiguous dreamscapes to encourage us to examine our own interior worlds.

Serena Bentley is a New Zealand-born, Melbourne based curator and art writer.