In the lead up to un Projects' 20 year anniversary, we hosted Language Ecologies, a day of panel discussions, readings, and performances that explored the multiple ways language and writing emerges from, and shapes, artistic practice. Situated in James Nguyen’s exhibition ‘Open Glossary’ at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Language Ecologies fostered discussions on publishing, storytelling, self-determination, togetherness, entanglement, digital networks, and language materiality.

For un Extended, we asked three attendees — Ren Jiang, Wen-Juenn Lee, Madison Pawle — to write a response to Language Ecologies.

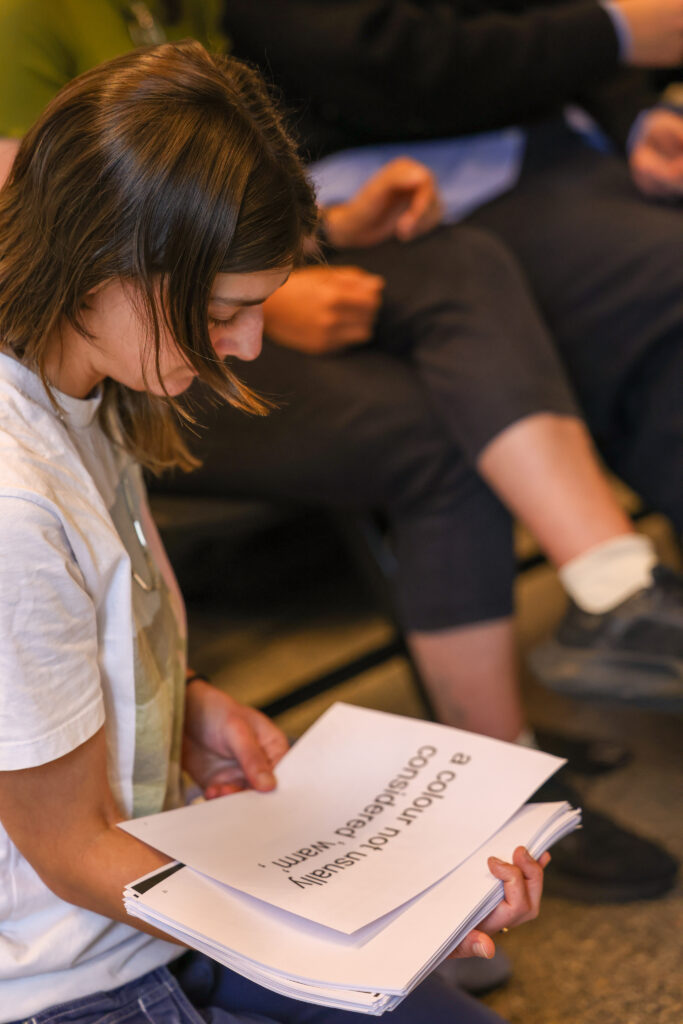

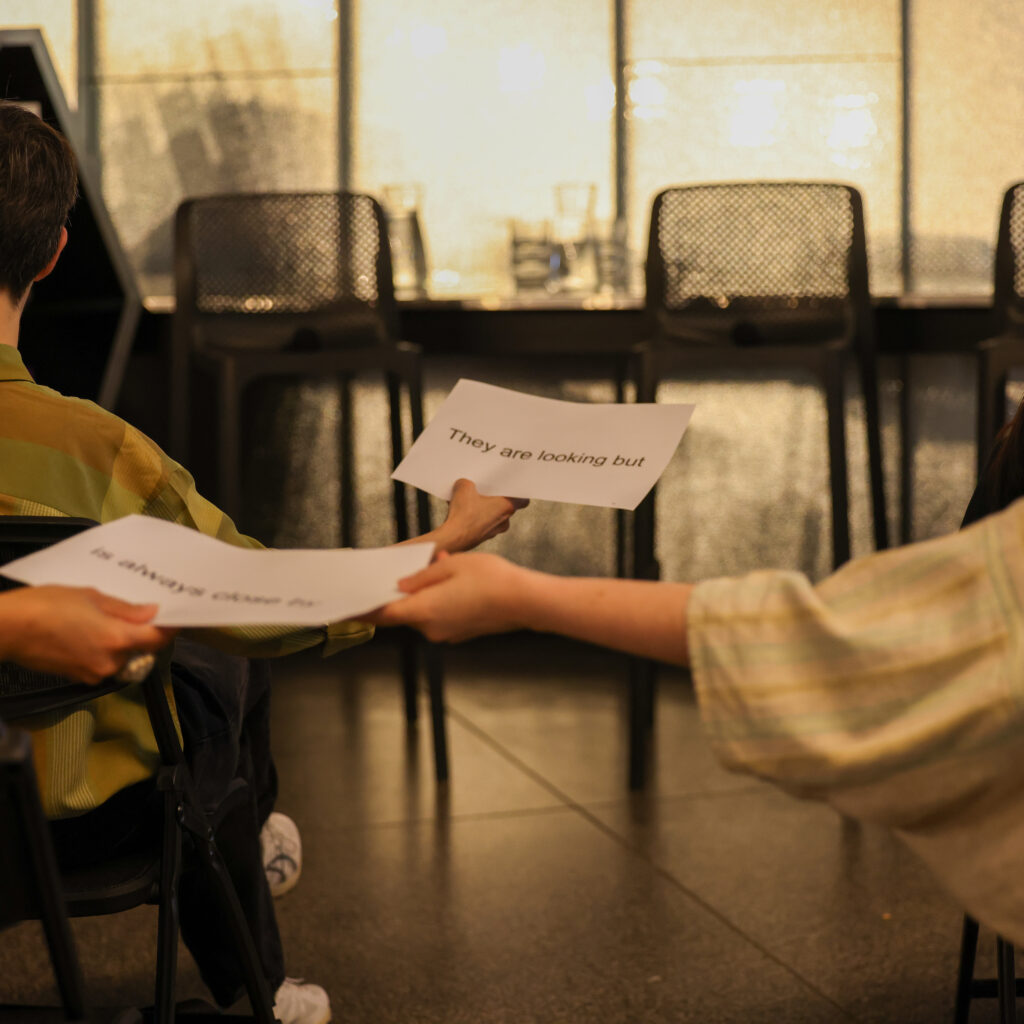

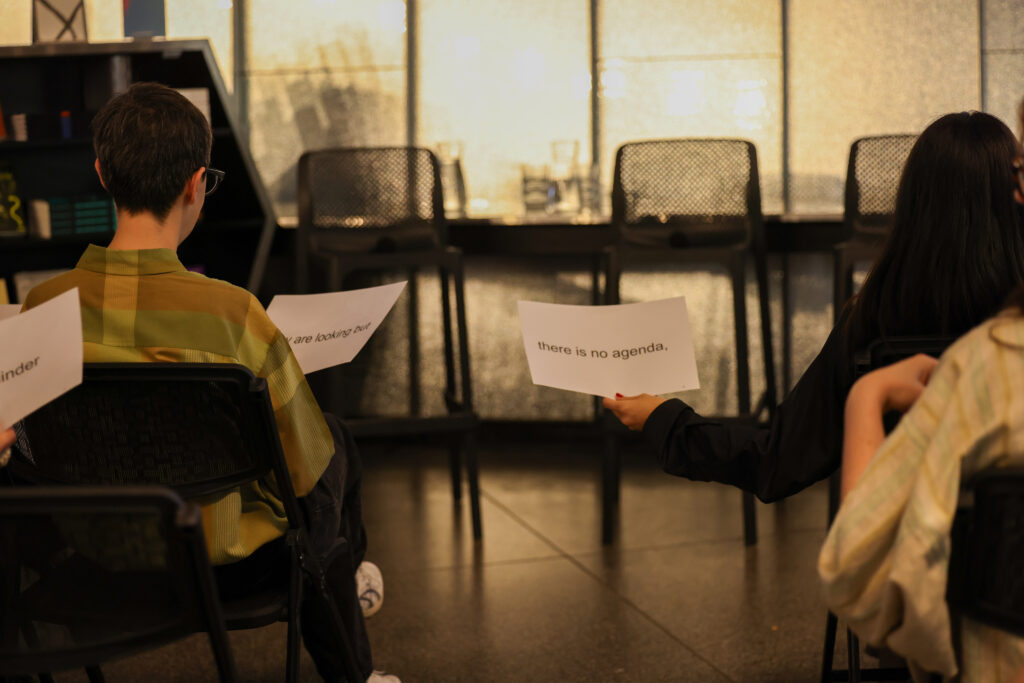

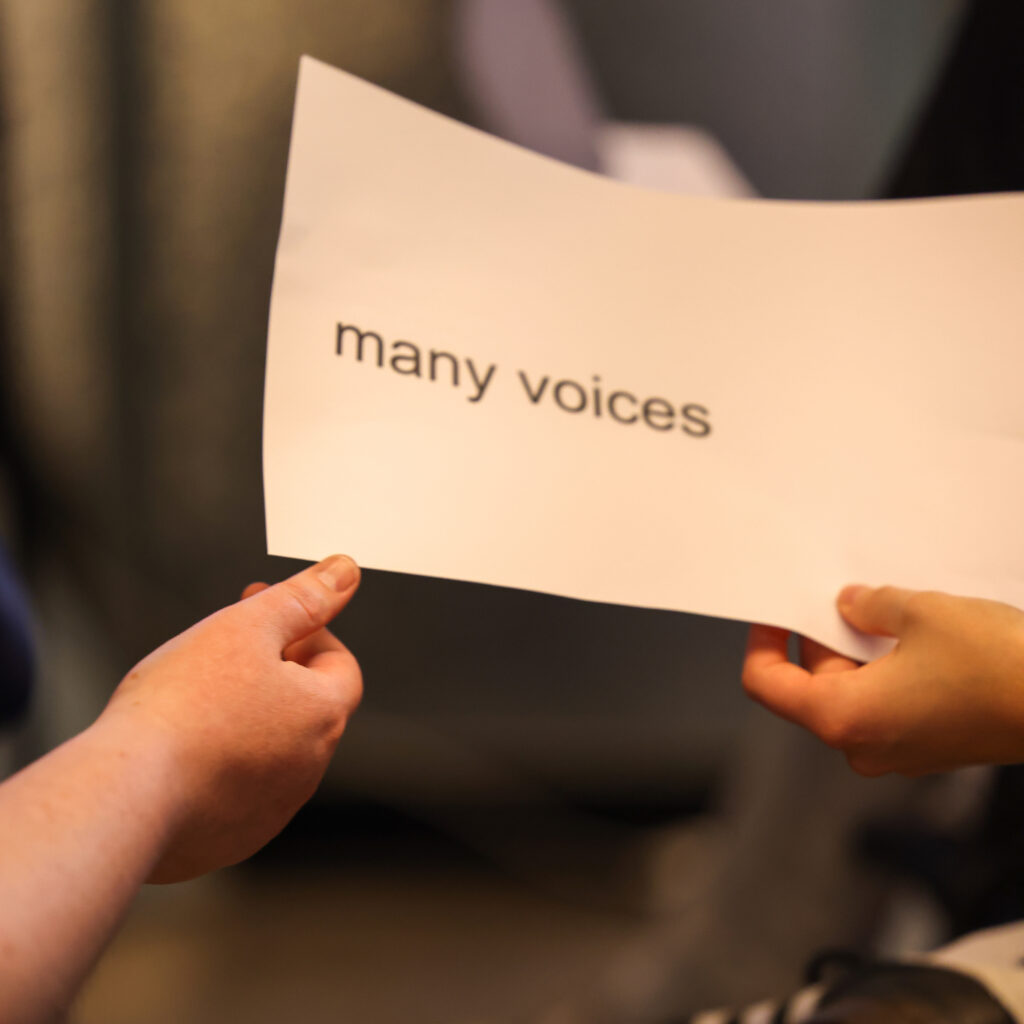

We attempted to coordinate an arriving-together to ACCA but we failed and instead met on the seats inside, gossiping over instant coffee and lemon ginger tea as we waited for Language Ecologies to begin. Gossip, as Snack Syndicate writes, “moves through and across social bodies, and yet is always bound by relations of intimacy, trust, and positionality”.1 Gossip happens in the break, in the between, in the beside, about and around dominant forms of speech. In Rosie Isaac’s public performance reading exercise, Isaac recounts a dream through a series of clipped phrases, scanned photos, and radar images. The audience was instructed to read, either silently or aloud, and then pass it on.

A week-or-so later, we sat at one of our kitchen tables and, over taramasalata and corn chips, we considered how to respond to Language Ecologies. To continue speech that moves across social bodies, we set a structure. We would write in response to each other but constrained by a particular order. The structure of writing first, second or third parallels the logics of an ecology; circularity and fixed positions are necessary for flux and change, one is indebted to the other, one works off the other, one sits beside.

Psst. Come squat on the nature strip with me. Lift this rock.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was an ant thumping on its abdomen, or a turning leaf, or a single buccal floor vibration from a karaurus, throat gorged in a quick gasp of fresh—

—and somehow, sometime, also in the beginning, there was Nothing. Sometimes the only Word on the page is a squiggly, smudged “-velength”, run off the page by blurry radar images of seawater. I open my mouth to garble: “Ninety-six”… “blue”… “today”…

I’m trying to isolate the sound of my voice without saying something. I want us to put our lips together and make a seal with our mouths, and then say “AaAAaaaAAAAHHhhhHHHHhh” as loudly as we can, feeling the vibration on our faces.

Sheila Heti’s Mira finds herself in a leaf with her dead father. Desperate for confirmation, she asks him to answer her calls. He replies that “he is here. But he doesn’t want to talk.”2 In death, in wordlessness, “his peace is greater than hers”. Or does it just mean that sound has a greater wingspan than words, and so can reach further, hold tighter?

You could tell me how crunchy an apple is, just by chewing it.

You’ve got me thinking about besideness, touch and collapse.

What kinds of relationality does “beside” invoke? In Touching Feeling, Eve Sedgwick considers the “beside” as a position that might give us some relief from “implicit narratives of…origin and telos” that other (Western) modes of meaning-making travel along.3

Your index finger directs my gaze and urges me to move. I lift the rock. Squatting together, we listen. Your finger is the word and the sonic field that emerges from beneath the rock (and: from your body beside mine and the street and the wind through the plane trees and the homes and the distant sky and the…) is the Word. Beholding, as Fred Moten tells us, “is always the entrance into a scene, into the context of the other, into the object”. 4

Visuality haunts the sonic. There are ways through this: repeat “the hot blue radiation of the sun” seven times and feel the words collapse into a hum.

Rosie Isaac asks us to think about how the act of reading moves out from the interior. Sure, there is stuff going on inside us when we read – synapses collide, worlds form – but what of the body? My arm gets sore as I take and give each piece of marked paper. My tongue shapes sound. Your voice travels along my inner-ear canal to move the fluid in my cochlear. And sometimes, inside this scene of polysyllabic vibration and echo, my hand touches yours.

What you say about ‘beside’ makes me think of ‘about’. ‘About’ circles around and around, but it never arrives. We are liberated if we are beside, or around, or near. We are not trapped by destination. Nicole Sealey writes, ‘How have we managed our way/ to this bed—beholden to heat like dawn/ indebted to light.’ 5 To behold as always an act of light, an act of straining towards proper attention. In the beginning was the Word, we say, but in the Word, let there be light. So, light pools on paper, on sound, on the rock that we listen to until we notice something like heat.

Heat is friction—like my hand touching yours, or the clang of a true word burning itself in my mind. My friend will only read the things she loves aloud, which is different to the idea that sacredness is private, unnamed. In this case, something loved is something spoken; in the act of reading out, something is moving, like light. We turn the pages, we speak, we arrive at the end eventually.

‘I asked him how he came to be a painter,’ Annie Dillard writes, ‘He said, “I like the smell of paint.”’6 The paper is fresh from the printer, warmth softly leaking, and I am handing it over, repeating, blue, blue, blue. Sometimes, we abstractify until we forget its origins, but it begins here: I just like the smell of paper. Once, a friend in high school boiled sheaves of paper to make me a perfume. But the perfume she ended up with was cloudy, acrid. Something had died in the process, but I still loved her for it, perhaps even more. To boil something is to whittle away, to strive for comprehension. ‘I have never understood a single poem,’ Mei-mei Berssenbrugge said.7 Not comprehension then, but a sound, deeply knitted to the body.

I hop on one foot and shake my head floor-ward to dispel the heat spilling from my ears.

Nuar Alsadir writes: “We leak truths from our bodies all the time.” 8 But you both know that.

On so many afternoons, I sat at a corner desk against the glare of the sun. It’s Rainbow Magic pages and Silent Reading Time. Squelch squelch, suck suck, the room is a cacophony of milk teeth gnashing on fruit. The mincemeat sound of all these textures make me queasy. A girl takes one small bite from every chip before returning it to the packet. I try to focus on the smell of the paper. My finger grazes a hardened stain on the corner of the page.

Do you ever get stressed about accidental touch? Sometimes the discomfort lingers in my body and I can’t forget the unintentional collision with a stranger, even if it’s just fingers on a shared page. The memory is overstimulating, and bounces from inner wall to inner wall like an itchy glob in my body. It makes me want to scream.

The Wilhelm Scream is a sound effect used since 1951 to dub distress and pain, but nowadays it’s mostly a joke between filmmakers. It’s an available voice option on some digital pianos. Sullen, seething, bored, I mash the key over and over again, the yell rising in pitch until the mechanic becomes whittled. I open my mouth a little every time I press the button—to really sell it.

I’m listening to The Wilhelm's demo recording session. 9 Sound is a raw slab, chiselled by the practised emotion of language. The first take doesn’t convey enough distress; the last one is overdone and too worn out. This is the first draft. What are we going to gain and lose in the editing process?

On the 11, a man’s thigh touches mine. He doesn’t seem to notice but all I can think about is his hair on my skin, the small heat at the point of contact, and whether I should move away. Unexpected and banal intimacies like this embarrass me.

All three of us are at different stages of reading the same book. We know this because someone brings it to a party and we all touch the cover and talk about it. It’s a coincidence, this shared attention, especially in the context of collaboration. Is this, too, a kind of accidental touching?

In her book, Nuar Alsadir writes about laughter – real, unguarded laughter – as an eruption of the unconscious. It’s the same with slips of the tongue and mistakes. I, for instance, am always late, even and especially when I am trying not to be. Being late was the reason I was on the 11 at 1.27pm. My being-late is rooted in a deep knot in my unconscious that may always elude my comprehension, “felt in moments, not in totality”. Here, Rosie Isaac is referencing the nature of a dream, another of the unconscious’ direct transmissions. Or, its tongue, its language, the raw slab. Dreaming happens in a suspended present tense. I am trying to put more words around this notion but it feels extremely resistant to language. It’s just a vibe. Or maybe it’s like the Wilhelm Scream.

Freud was interested in lapses of attention. You try to remember the name of a thing and it comes back while you’re doing something else, something unrelated. Reading aloud is a simple example of this in motion. We read each phrase as it is written but, a lot of the time, the mind is drifting: your hand, my arm, the smell of paper, the sound of a page turning. Freud didn’t think of these as moments of lesser attention, but as an intervention by an “alien thought which claims consideration”. 10 You repeat “blue” until you’re back in high school being handed a vial of clouded perfume.

The past is always accidentally touching the present, or friendship is the accidental touch of ideas. A writer was telling me about this book he was reading, a book that he couldn’t get out of his mind, and before he said it, I pulled it out of my bag. We both yelped, neither of us had heard the other make that sound before (a laugh, a cough, a sneeze, Alsadir writes, can signify the expulsion of foreign matter).

Animal Joy has also made me think about the quality of deadness; that if an analyst begins to feel sleepy when an analysand is talking, they are colluding on a false truth. The way people talk about clowning is akin to psychoanalysis. That you need to face the terror of who you are, and who you present yourself to be, to access something true, something like real, unguarded laughter.

What is at stake is a public and a private self collapsing. Reading as private, but also with the suck suck of other bodies, which is what makes a library so liberating. I live for the overlapping moments, the same book read—but we can still never talk within it, what makes the three of us drawn to it? We can talk beside, and around, and about.

Photography by Mischa Wang. Featuring a performance by Rosie Isaac titled 'Various Blues'.

1. Snack Syndicate, Homework, Discipline, 2021, p.268.2. Shelia Heti, Pure Colour, Penguin Books, 2023, p.99.3. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling, Duke University Press, p. 8.4. Fred Moten, In The Break: The Aesthetics of Black Radical Tradition, University of Minnesota Press, p. 235.5. Nicole Sealey, Object Permanence. https://www.aprweb.org/poems/object-permanence. Accessed on 10 Nov.6. Annie Dillard, This Writing Life, 1989.7. Chi Tran and Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, "‘I have never understood a single poem’: Chi Tran Interviews Mei-mei Berssenbrugge", 2017. http://cordite.org.au/interviews/tran-berssenbrugge/8. Nuar Alsadir, Animal Joy, 2022. p.96.9. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rksd5v43zxI&ab_channel=KairamenisBack10. Sigmund Freud, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, Penguin, 2002, p. 173.