Artists: Richard Bell (with As Long As It Takes), Marcel van den Berg, Blade, Alice Creischer, Bonita Ely, Ho Rui An, Gordon Hookey, Patricia Kaersenhout, Karrabing Film Collective, Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, Tom Nicholson, Wendelien van Oldenborgh, Rachel O’Reilly (with PALACE, Valle Medina & Benjamin Reynolds), Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Ryan Presley, Rammellzee, Farida Sedoc, The Otolith Group, Erwin Thomasse, Dondi White and Sawangwongse Yawnghwe; as well as loans from the Falconry and Cigar-makers Museum Valkenswaard, Collection G. Goven, Museum Helmond, Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, Milani Gallery and the Crochet Coral Reef, a project by Margaret and Christine Wertheim and The Institute for Figuring.

Curators: Vivian Ziherl i.c.w. Charles Esche and Annie Fletcher.

Frontier Imaginaries is a roving art and research platform founded by Amsterdam-based and Brisbane-raised curator Vivian Ziherl. Dedicated to studying the frontier in the global era, Ziherl emphasises that ‘the frontier is not a border.’1 Rather, it is better understood as a threshold, beyond which what exists is ontologically different to where the perceiver is located. In colonial contexts the frontier distinguishes between civilised and uncivilised territories, like the North American notion of the ‘Wild West’ or in Australia what is often referred to as ‘the Bush,’ territories over which settlers’ have long sought to exert control.

As Frontier Imaginaries comes to ground in Eindhoven for its fifth edition, Trade Markings, it is the related concepts of ‘territory,’ ‘property’ and ‘proprietary’ that are prioritised. The key navigating device for the exhibition is a ‘timeline/tideline’, Symphony of Liberalism (Eindhoven) (2018). Running along the walls through the entire exhibition, it charts events from the founding of the Dutch Republic ‘in the emergence of capitalist global relations’, to the present day. Akin to a musical score, the timeline is a visual analogy as used by philosopher and anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli, enabling one to see events chronologically and geographically in relation to one another, discerning patterns of harmony and dissonance. Thus, ‘we would begin to see glimmers of immanent alternative social projects across the variants of late liberalism’.2 At the Van Abbe Museum, local events are marked below the timeline in blue, while global events are marked in gold above.

Trade Markings as a title was suggested by the philosopher Denisa Ferreira da Silva, in reference to a sum-mary of the Modern agreement by the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotious in 1609 as ‘trade supported by the force of arms’.3 Thus, the notion of ‘freedom’ in trade agreements is ‘radically qualified’ by the violence inherent to its negotiations. Over the opening weekend, I made note of the Otolith Group’s Anjalika Sagar who re-phrased the title as ‘the markings of trade,’ highlighting the effects of globalisation on the enslaved and labouring classes. Indeed, early anticolonial and antiracist concepts, strategies and counter-histories also traveled along trades routes.

An artefact of one such history makes an appearance in Trade Markings: an engraved mother of pearl shell produced by an unknown convict in New Caledonia/Kanaky circa 1879. After the quelling of the Paris Commune in 1871 some 4000 Communards were sent to what was then a French penal colony. As many were skilled artisans and craftspeople, they began producing souvenirs for sale in local markets. The shell on display, depicting a battle scene and a military portrait, ostensibly valorises Colonel Gally Passebose, the youngest colonel in the French service who fell in battle during the first Kanaky uprising of 1878. Engraved on its reverse side is an enigmatic figure, ‘Camille B,’ whose mustache grows into twisting vines of wild roses. On top of his skullcap, an emancipated angel dances victoriously above a ‘common world’, holding a torch aloft.4 Janus-faced, the object has a talismanic quality given that this year marks the anniversary of the signing of agreements towards Kanaky independence in 1988 and 1998, culminating in a referendum this November.5 Installed in a vitrine in the centre of a room, the shell is surrounded by three detailed paintings that symbolise another struggle for liberation from colonial powers, by Brisbane-based artist Ryan Presley who is of Marri Ngarr ancestry.

A prominent work in the exhibition is Waanyi Aboriginal artist Gordon Hookey’s ongoing series of epic history paintings, putting a distinctly anticolonial and anachronistic spin on the history of the artist’s home state. Wryly titled MURRILAND! (2015–ongoing) ‘because Queensland is England’,6 the ten-metre-long paintings combine motifs from Aboriginal cosmology, historical characters and caricatures of political and media figures. The first of these was exhibited in progress at Frontier Imaginaries’s first edition at Brisbane’s IMA (2016), then completed for last year’s documenta 14 in Kassel. Hookey worked in situ in the first room of Trade Markings over the initial three weeks of the exhibition, engaging gallery patrons in conversations to shape the second painting.

MURRILAND! responds to the remarkable ‘genre paintings’ of Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu, a ‘historian and artist’ who produced 101 paintings of the ‘History of Zaire’. Hookey was introduced to these works by Ziherl during a period in which he admits he had ‘[given] the art world away’.^7 Using flour sacks as his canvas, Kanda-Matulu presents a counter-history to the official Belgian historiography he encountered in schoolbooks, with particular focus on the Democratic Republic of Congo’s first Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba, an iconic figure in the struggle of African independence. The works were commissioned by the German anthropologist Johannes Fabian following a chance meeting8 and were painted over two months. Kanda-Matulu disappeared in 1981 and in 2000 Fabian negotiated with the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam to purchase the paintings, specifying that they were only to be exhibited in their entirety.

For Trade Markings, a selection of Kanda-Matulu’s paintings are placed sequentially along the timeline/tideline across several rooms of the museum, building towards an impressive crescendo in which Hookey’s completed MURRILAND! painting is exhibited opposite a salon hang of the majority of Kanda-Matulu’s 101 paintings. Negotiating the space between these monumental undertakings are seating blocks designed by the Dutch-Surinamese artist Farida Sedoc. Upholstered with boldly patterned ‘wax hollandais’ fabrics, a satirical swipe at Dutch company Vlisco which dominates the market for luxury ‘African fabrics,’ Sedoc’s blocks are paired with Astroturf mats, stenciled with slogans that proclaim: ‘Sit down. Be humble’ and ‘Seize the Time’.

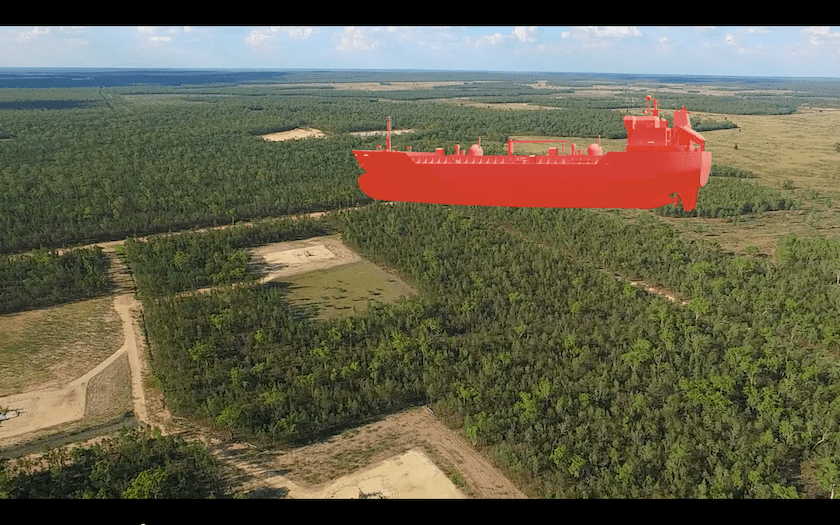

Rachel O’Reilly’s The Gas Imaginary (2013–ongoing), a work of infrastructural and artistic research, also requires close attention. Responding to the install of the fracking industry in Australia since 2009 through her hometown port city of Gladstone, Queensland, on Gooreng Gooreng land, it is another evolving series comprising prints, video and text. Set inside a gallery enclave, two series of black and white risograph prints, The Gas Imaginary (2014) and Gladstone, Post-pastoral (2016) encircle the space. Made in collaboration with (post)-architecture collective Pa.LaC.E (Valle Medina and Benajmin Reynolds) and visual artist Rodrigo Hernandez, in dialogue with Gooreng Gooreng elders, the imagery of annotated cross-sections, graphs and diagrams pitch Australian dreams of home ownership against the anxieties of new toxicities in settlers’ backyards, undercut by ongoing Aboriginal dispossession. In the Netherlands it is notable that the vessel that destructively dredged the Gladstone Harbour is owned by a Dutch-Australian company and named the Rotterdam. For the accompanying video, Drawing Rights (2018), also made in collaboration with Pa.LaC.E, these monotone diagrams are tinted rose and extruded as 3D computer graphic tableaux. Animated with camera fly-throughs, these motion sequences complement O’Reilly’s poetic analysis of the legal innovations that enabled private property ownership and colonial land transfers in Australia and was subsequently adopted around the world. For example, in one scene a gas tanker is buried in cubed topsoil, alluding to the top 4cm that Australian property owners are entitled to, with everything below reserved by the government as mineral rights. In another cutaway the camera tracks past a stack of duplicate turtles, illustrating the logic of false equivalences that O’Reilly critiques. The urgency of this work only becomes more apparent given the recent decision of the Northern Territory Government to lift its two year moratorium on fracking. Fifty percent of the Territory is Aboriginal-won land almost fully dependent on groundwater.

The Karrabing Film Collective presents a specially commissioned new work, The Mermaids, Mirror Worlds (2018) the first multi-channel piece by the Northern Territory-based mob. Flipping between two screens, The Mermaids... opens in a Darwin hospital, following two medics in radiation suits tasked with cleaning up after an inpatient succumbs to an unknown illness, their body melting away from the inside, a fatal epidemic to which Aboriginal people are oddly immune. The film follows Aiden Singh, a teenager who was removed from his family as a child as part of experiment to ‘save the white race,’ as he is reluctantly returned to them as a confused and angry young man. The Karrabing characters drift across bush landscapes poisoned by white people and their extractivist industries, pursued my authorities in radiation suits. I later learn the video is a ‘story performance’ of Blowfly Dreaming, which has the capacity to destroy all life on earth, hinting at a delirious revenge fantasy of people once marked a ‘dying race.’

An adjacent screen alternates chapters of the Dreaming story with a selection of publicity videos from Dow Chemicals, Monsanto and the Economist. Extending the device of the mirror, this corporate propaganda is altered with video and audio effects, accentuating the warped logic of multinationals proffering proprietary-protected biological manipulation as the solution to the consequences of industry-led ecocide. Indeed, I found a Dow Chemicals’ promo pitching their corporate capture of the ‘human factor’ much creepier than any of the malevolent spirits and demanding ancestors of the Karrabing’s worlding. To cite Povinelli: ‘settler late liberalism is not so much an inverted mirror as a funhouse mirror’10 and the juxtaposition of these two versions of reality certainly challenges viewers to decide which is the most freaky.

Ziherl leads her editorial for the Trade Markings’ issue of e-flux journal with an epigraph from critical indigenous scholar Aileen Moreton-Robinson’s recent book, The White Possessive: Property, Power and Indigenous Sovereignty (2015): ‘The problem with white people is that they think and believe they own everything’. So it seems significant that for her opening address Ziherl adopted the Australian custom of delivering an Acknowledgement of Country at formal events, a recognition of prior ownership of land by Aboriginal people that is ambivalent to settler society’s ongoing dispossessive charge. Ziherl invited the Winti Priestess and scholar Marian Markelo of the Surinamese diaspora to deliver a ‘libation’ — a ritual offering — foregrounding the presence and struggles of colonised people who continue to shape Dutch society. Here, it is worth noting that the Van Abbe Museum, amongst a confederation of museums collaborating as L’Internationale, has committed to processes of decolonising, demodernising and decentralising its practices.11 Arguably then, Frontier Imaginaries performs a para-institutional critique by showcasing often overlooked contemporary cultural practices that have formed outside of European ontologies and also arise within it, amongst the historiographies and aesthetic forms that contribute towards its study of late liberalism.

Boris Groys argues that the role of contemporary art is to perform knowledge; to expose and exhibit forms of life in a globalised but differentiated world. He likens such exhibitions to a stage on which the contemporary is performed. Thus contemporary art constitutes performative rather than contemplative subjects, who are compelled to change themselves, to ‘take transformative action, transform the world, and so on’.12 Indeed, Trade Markings addresses me as such. As a nomadic and evolving program, Frontier Imaginaries collects diverse ‘humans of the institution’13 — artists, arts workers and patrons — stirring up political imaginaries as a call to act.

Sumugan Sivanesan is an artist, writer and researcher currently based in Berlin.