Exhibiting artists

Ceri Hann, Danielle Freakley, Eric Demetriou, Gabriella D'Costa, Jacqui Shelton (with Alice Heyward and Megan Payne), Jake Moore, Makiko Yamamoto, Mel Deerson and Briony Galligan, MP Hopkins, Simon Zoric and Steven Rhall.

Performances

Ash Kilmartin, James Rushford and Rachel Yezbick, Jacqui Shelton (with Alice Heyward and Megan Payne) Jake Moore, Kate Brown, Mel Deerson (with Briony Galligan), Melody Paloma, MP Hopkins, Sonia Leber and David Chesworth.

Curator

Joel Stern

The following is a series of thoughts written after the closing of the group exhibition Ventriloquy shown at Gertrude Contemporary and curated independently by Joel Stern with an accompanying public program presented by Liquid Architecture. Ventriloquy was the nineteenth edition of Gertrude’s annual flagship exhibition series Octopus, where an external curator is invited to present an exhibition.

It’s important to be cognizant of the mechanisms in which art discourse, namely exhibition reviews, function. Exhibition reviews are, in effect, giving a voice to an exhibition in ways that didactics and press releases can’t. Mine is, presumably, a less biased voice — a voice for which the audience of the exhibition, both real and projected, can identify with through a shared experience of seeing and not staging. If written well and in a spirit of praise, exhibition reviews sublimate and provide an axis of legitimation for a now-muted exhibition. Given the show is over at the time of writing, and in its place another is mounted (currently on view at Gertrude Contemporary is the inaugural annual commission initiative in partnership with investment firm River Capital), it provides this text with a space to not be misheard as promotional nor to speak on behalf of the show. Within a ventriloquial space, the question of voice and whose voice and from where it comes is critical.

Adapting this review even further to the logics of the voice that Joel Stern outlined and invited the viewer to consider in this project (and his curatorial and research practice more generally), the voice of this review is one on delay. A delay in a ventriloquist’s performance breaks the magic. If the voice of the ventriloquist and the mouth of the dummy (a proxy for the hand of the ventriloquist) aren’t in unison, the performance and, importantly, our perception of it (the audience enables the performance to work through our suspended disbelief) breaks down. It’s unclear then if it becomes bad ventriloquy or if it ceases to be ventriloquy entirely. Georgia Hutchison, of Liquid Architecture, made an important note to me on ‘the delay’ as a tool for illumination. The performance of the ventriloquist is amplified only when a delay occurs; it renders the performance and circuitry of the vaudevillian gesture visible. This seems to imply that ventriloquy itself is seen only when performed poorly.

Upon entering Ventriloquy, the printed matter of Danielle Freakley’s work notifies us that we’re ‘welcome to try borrowing mouths here and lend [ours] out for a bit too.’

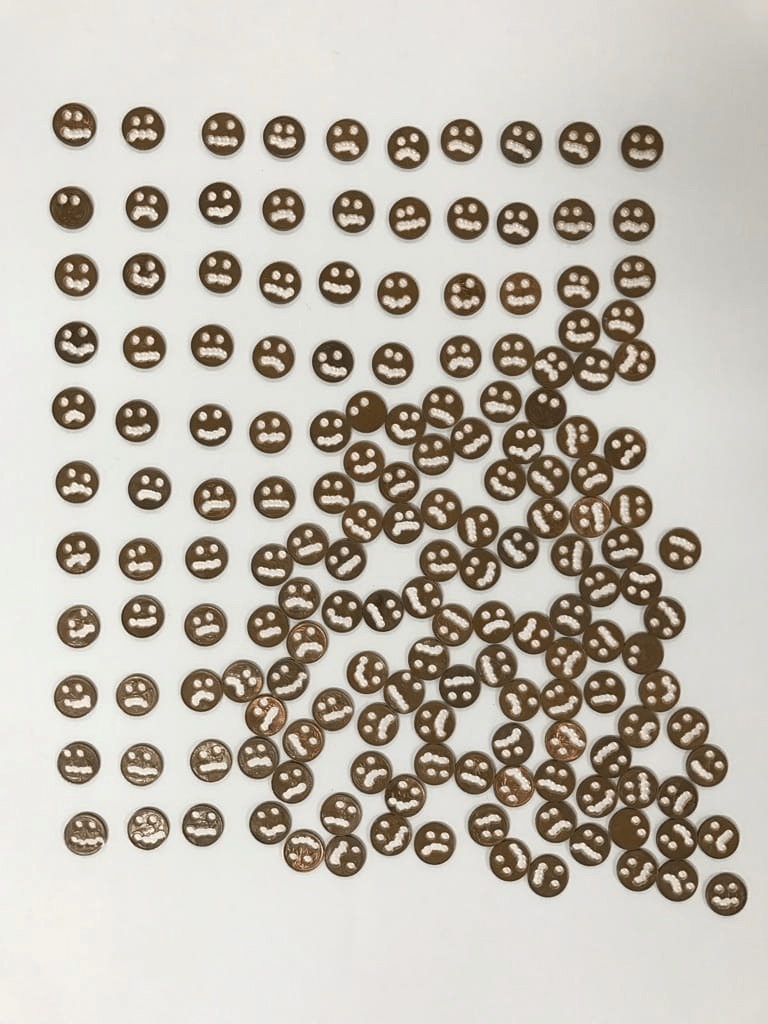

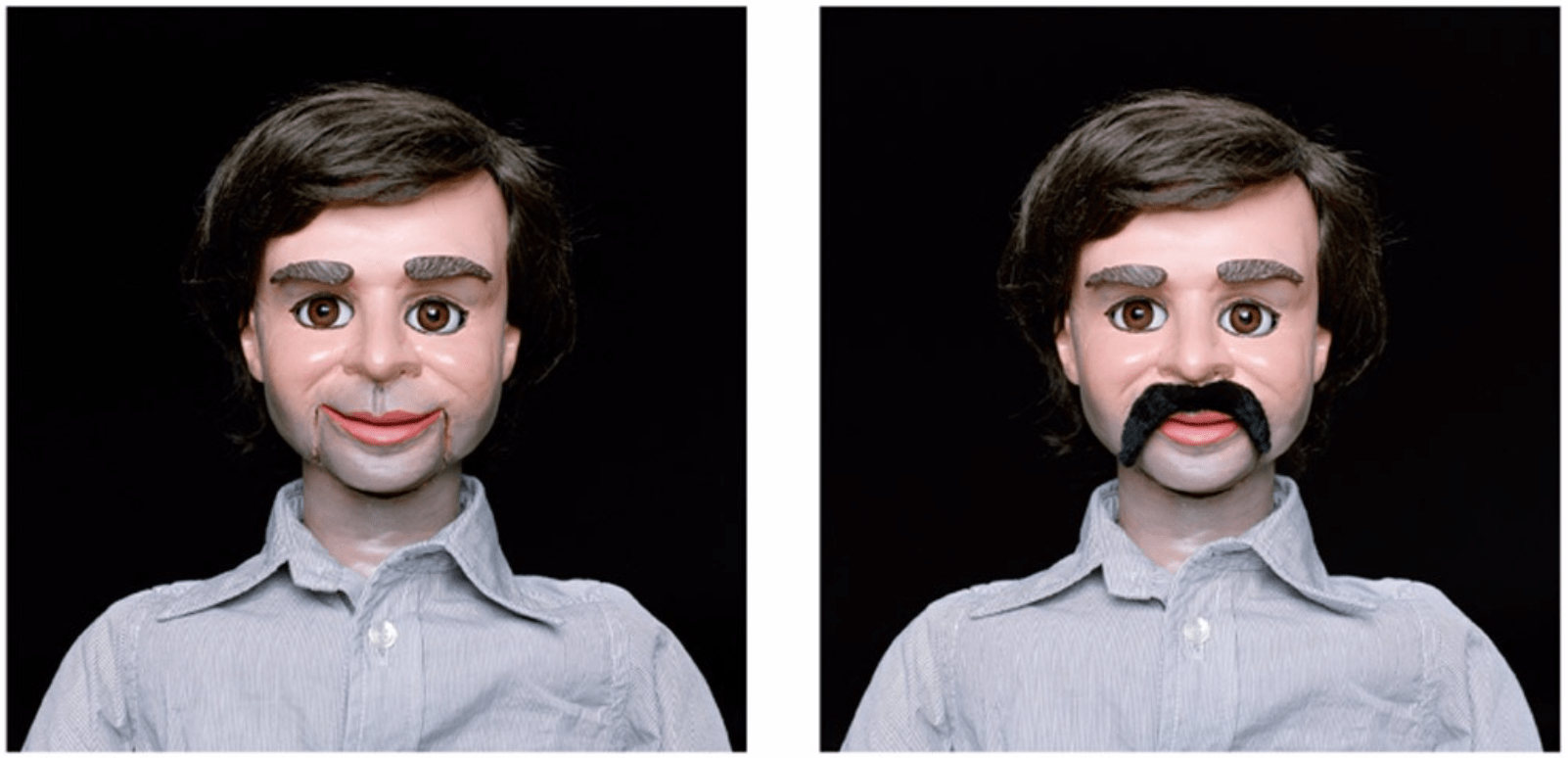

An extensive public program of performance works, which took place across multiple venues, accompanied the Ventriloquy exhibition. It was an ambitious investigation that brought together twenty-one artists (many of whom presented multiple works) across three venues. For the purposes of this text, I will focus primarily on works that were on view in the Gertrude Contemporary installation, which included new commissions and older works by Australian, First Nations and international artists. Divided into three sections, without explicit theoretical or historical demarcation, the works were installed in two galleries (one white cube, one black) and in the reception area at the entrance of Gertrude Contemporary. Four of the works traversed the three sections. One of two works by Ceri Hann, Money Talks (2019), a series of pennies with sad, happy and indifferent smiley-faces hole-punched into them, was scattered across all spaces. The sculptural dimensions of Jacqui Shelton’s video installation Crush (2019) were also scattered around the galleries, a number of bollards and red velvet ropes left as detritus from a dance-based work performed by Megan Payne and Alice Heyward during the opening and closing receptions. Gabriella D’Costa’s contribution Bureaucratic agency/Agency of Bureaucracy (2019) was also composed of bollards, but the signage type with plastic frames fitted atop, which encompassed a series of texts appropriating labyrinthian examples of corporate policies, procedures and other directives. Mysteriously, the other work that appeared across all three exhibition spaces was a ventriloquist dummy called Simon by artist Simon Zoric. Simon (2009) was seen as both a readymade sculpture and a performer, with a video work also on view in the exhibition. I saw the show twice and on my second visit the doll was in a different place than I had remembered. After appraising the didactics and floor plans, I noticed that he was listed as a ‘roaming performer.’

The Ventriloquy project (or ‘investigation’ as Liquid Architecture calls it) privileges the dummy/ventriloquist relationship as it models and maps systems of power, agency, choice and authenticity. Most of the works on view demonstrated concerns with contemporary life as one of societal control, or puppetry, with a higher power and/or actor being in control. An embodied state of disassociation, disentanglement and disidentification to or with our own bodies, voices and positions. As in works like That Sinking Feeling (2019) by Eric Demetriou, an ominous sculptural piece around an interpreter booth signaling administrative aesthetics likely to be used in court and/or auction house. Or Danielle Freakley’s Your Second Hand (2019), a clothes rack with previously worn items available to people seeing the exhibition. Each item had a tag that read: ‘In wearing this garment you will unconsciously inherit certain thoughts and behaviours from its previous owner.’ A warning about markets and property fixed to the scale of the human body, life-sized? These works invite us into the logics of ventriloquy as everywhere and as experienced everyday, demystifying, to some extent, the role of magic, trickery and anachronistic reading of ventriloquy. Experienced in this way, Joel Stern’s proposition of the ventriloquist and their dummy equates only to a metaphorical gesture played out against the backdrop of ventriloquial qualities experienced directly in our political reality. Ventriloquy as simply a metaphor to visually capture an interrogation of the common sense argument that ‘having a voice’ provides us with political and social agency. I suspect that my resistance to group exhibitions that are ‘about’ a ‘theme’ is influencing my reticence toward this reading. And, I’m further unsatisfied with this reading as it would be to play too closely into the mechanics of ventriloquy — the presentation of artworks (dummy) as vehicle for a thematic concern that maps onto the contemporary conditions of life via metaphor — as per the performance of illusions (curator). Illusions refer us away from factual existence, one of contemporary arts’ most common tricks. That is not happening here.

A more interesting entry point to me is the spatial and social context of the oral cavity and, thankfully, Ventriloquy is very mouthal as well as super-structural. One of the works that demonstrates both is Aboriginal Art Affects (2019) by Steven Rhall. The almost invisible sculpture was installed in the roof as a vent; when you walked past a certain point it triggered an extremely loud fan concealed from view. Inside the vent a small red ribbon flails in the artificial wind — similar to Rhall’s other works with air dancers, but this time the body is replaced with a tongue. The work reminds us that the white cube, or the stage of ventriloquy, is as much a body as it is a machine for the perceiving of culture and the receiving of affects.

While Ventriloquy attends more to the question of whether or not we, as constituents of the state, truly belong to our own voice, it is at its core a game of the hand and mouth and whether or not the mouth can be used as a tool beyond its rudimentary functions as a speech machine and an eating machine. The act of ventriloquy interestingly evades the lips but stays in the oral. It’s a gesticular performance of the voice and the speaking/eating hole, notably a non-mouthal (a machine which includes all operative functions of the mouth) exercise. So, given I’ve said ventriloquy is non-mouthal, what constitutes a mouth? It depends how far down the digestive track you want to go — the intestines and the asshole could be a part of the mouth if you wanted them to be but, traditionally, the mouth is the collective term for the lips, teeth, gums, tongue and perhaps the uppermost sections of the throat. This dimension of the ventriloquy ‘theme’ was notably present, and guttural, in performance works by Makiko Yamamoto and Kate Brown, both of which demonstrated the mouthyness of the curatorial position. Yamamoto’s spoken word performance was made increasingly difficult to hear amid the growing amount of saliva building up in and escaping her mouth. Kate Brown’s work too performed the ‘outside-inside’ of language, utilising the gag reflex as form.

Interestingly, this is not the first of Joel Stern’s curatorial efforts to be situated in and concerned with a cavity of the human body. Developed collaboratively with James Parker of Melbourne Law School for the Ian Potter Museum, Eavesdropping (2018) was more academic, less playful, and explicitly aligned itself with legal histories and figures. And yet Eavesdropping, I remind you, was an affair of the ear. It’s an adventurous and nonlinear way to present art discourse — the field of practice and presentation as guided through the various orifices of the human body. Ta-dah, psychoanalysis!

Ventriloquy is deeply concerned with principles of psychoanalysis, perhaps most prominently expressed in a short paper accompanying the exhibition written by Stern in collaboration with Danni Zuvela called ‘Narcissism and its Echoes: Notes from Steven Connor’s Knee.’ In this text there is heavy emphasis placed on the materiality of the voice itself, departing slightly from the mouth and the performance of throwing voice seen in the exhibition. Predictably, I jump to Lacan, who in 1953 famously disavowed the psychoanalytic academy for their abandonment of ‘speech’ itself (not the content of what is spoken) as the fundamental material concern from which psychoanalytic treatment and theory should emerge. The understanding of ventriloquy as one of subject formation was omnipresent among much of the exhibition’s works. An attempt to rescue the voice from the superstructure of artificial desire — as produced through us under the ventriloquial higher powers guiding our speech (desire) through nefarious means — is made by relocating truth (in speech) via the machine of artistic practice and discourse. Within the arrangement of psychoanalytic practices, the ventriloquist poses some interesting consideration. Ventriloquy, the act not the exhibition, is about disassembling our identities into fragmentary parts. It’s an effort of the performer and of the state to conceal or hide or redirect or throw speech elsewhere, to another (real or plastic) eating/speech hole, whether for entertainment or for purposes of political mobilisation. Speaking through another is, in some ways, about theft and impersonation — but speech can be full in the Lacanian sense even when its articulations are untrue. A schizophrenic voice may be unreal but it’s not necessarily without value. Art has value, maybe. Is the dummy a short circuit to the subconscious? If your analyst isn’t looking at you face on, which they often aren’t, does your performance of ventriloquy even matter? Is Lacan Freud’s dummy? These are all, somehow, very interesting and important questions.

‘[T]his is where the fantasies of speaking in tongues, the expressivity of the untrammelled id, comes in. It is hard to abandon one’s voice completely. But closed mouths and loose tongues can speak other truths too.’ 1

Thomas Ragnar is an artist and writer based in Naarm. His work is often underpinned by collaborations.