Gallery: Fiona and Sidney Myer Gallery

Exhibition: Arthur Jafa, Unrest

7 April - 13 May

I am a Wiradjuri guest on the unceded sovereign lands of the Wurundjeri peoples of the Eastern Kulin Nations. This is where I live, work, and am writing from today. I am paying my respects to Elders both past and present. Wurundjeri mob and their forebears have been custodians of this land for millennia. I stand on the land where Aboriginal peoples’ have performed age-old ceremonies of celebration, initiation, and renewal. I acknowledge the living culture and the unique roles in the life of the region. I recognise and respect this cultural heritage, the beliefs and relationship with the land; these continue to be central to the Kulin peoples of both past and today.

When winding through the rabbit warren that makes up Southbank to enter the Fiona Sidney Myer Gallery, the dark, cool space envelopes you at the same time the Kanye West song Ultralight Beam consumes you. The space swallows you whole and transporting you back to its release. I reflect on how every day we are forced to weave through the mazes that the pervasive, heteropatriarchal, racist, violent, colonial supremacists have knowingly planted and pruned at their will. The gallery room is still with clear, understated, black signage that welcomes you to African-American queer artist, Arthur Jafa’s solo exhibition ‘Unrest’. Two artworks make up the entirety of the exhibition: Love Is the Message, the Message is Death, 2016, technicolour video, seven minutes and 25 seconds, looped, and The White Album, 2018, technicolour video, twenty nine minutes and fifty five seconds, looped.

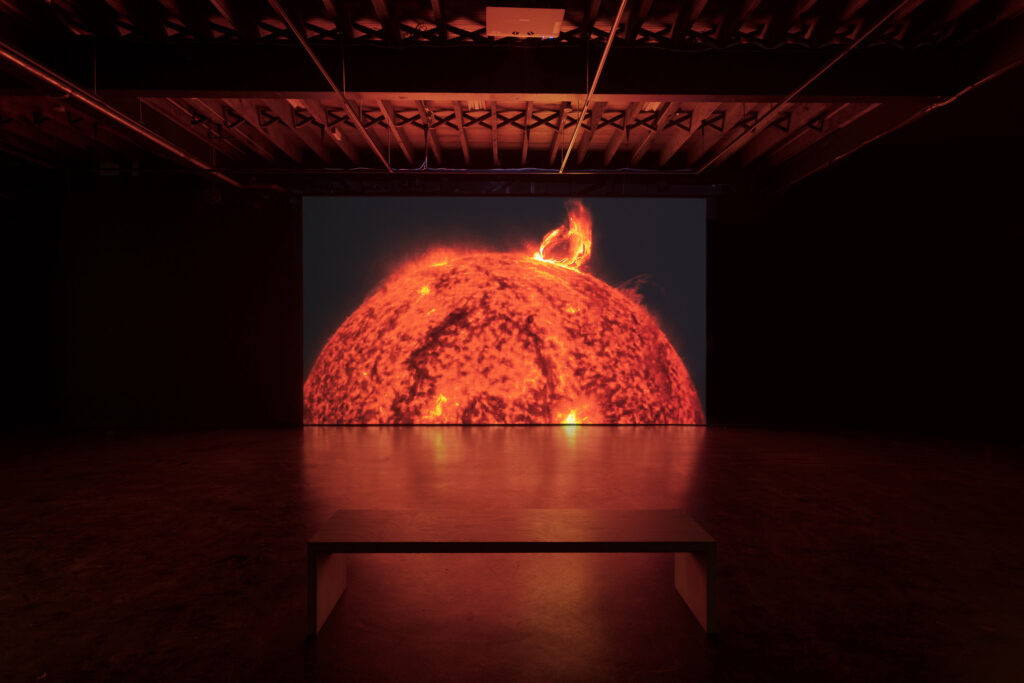

An archway opening to the left of the gallery beckons the viewer to indulge in curiosity and find the source to the audio. Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death is playing on a large screen with a simple, single bench for the viewer to perch on. Gospel singers, such as Kirk Franklin, have had their voices collaged amongst RnB artists, The Dream and Kelly Price, in addition to Chance the Rapper’s contribution are what make up the vocals of the film’s song, Ultralight Beam. The juxtaposition and variety of voices in Ultralight Beam mirror the visuals that Jafa has compiled in collage-style video work. Transfixing clips of Jafa’s personal life, footage of police violence against various Black people, dance circles, memes, children crying, and voguing dancers all make up the work. Jafa’s tampering with the audio creates tension between the viewer and screen, my ears succumbing to strain, attempting to hold the weight of each word amongst the myriad of continuous monumental yet non linear history. For example, the artist inserts Barack Obama’s rendition of Amazing Grace, both complementing yet disrupting the flow of the original music choice.

Love Is the Message, the Message is Death is critiquing settler colonial supremacy and its unquenchable thirst for fetishising and objectifying Black bodies while simultaneously enacting harrowing state-sanctioned violence and assimilation. An amalgamation of visceral emotions overcome and grasp me; though for many Black and First Nations peoples, these videos do not come as a surprise but as a means to contextualise experience with clarity. Jafa has managed to expose an overall rawness while weaving in moments of Black joy and Black humour.

Traversing into the room, the viewer is bathed with a flat, red reflection; the screen forces the audience to hold this bloody illusion without the buffer of music. Upon entry, my first reaction was that the score of The White Album had been deliberately chosen to host the presence of the previous work as the terror of vermillion and silence felt excruciating. But just as the overflow of Ultralight Beam stopped billowing into this artwork, it became clear that the narrative of The White Album feasts on varying and specific lingual aspects.

While the construction of this The White Album initially appears alike to Love is the Message, the Message Is Death, instead this work predominantly places whiteness as the centrepiece. As a result, the work produces pungent cringing responses from the audience to the punitive verbal punishment that floods the audience’s ears. Video clips span scenes of ignorant white women, an audience member of a sporting event performing and lip syncing to Bon Jovi’s track Livin’ on a Prayer, police violence, snippets from iconic films and punitive acts of profanity, Jafa splices in moments of white absurdity and chooses to end on a monologue of white self awareness and national shame.

Watching The White Album, I couldn’t help but be reminded of my teenage years and of the people around me: the young white teenagers who ‘couldn’t see colour’, the fragility surrounding privilege, the lack of interest in wanting to learn, the disdain of these same people when in the presence of a Black person. Ten years later, now watching this artwork, a video compilation of individuals who are reiterating and rehearsing those same ideologies back at me, it feels as though little has changed in a decade. Throughout the eclectic series of archival footage, The White Album additionally reveals the artist’s dark sense of humour and the horrendous normalised realities — we see an animated, gaunt version of Iggy Pop juxtaposed against a snippet from the 2017 A24 film Good Time, then followed by CCTV footage of Dylann Roof exiting Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston where he murdered nine people in 2015. Jafa exposes a glimpse of hetero-patriarchal structures of white settler supremacy in all its different forms.

As a solo exhibition,‘Unrest’ demonstrates the complexity and nuance of what Black people are forced to navigate daily, from the absurd to the disturbing. This is what Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death highlights and The White Album elaborates on. These video artworks are woven together in a way that feels similar to the winding path that holds them, guiding the audience to duck and weave with Arthur Jafa’s societal reflection.

Elijah Money (he/him) is a queer Wiradjuri brotherboy who was raised on Kulin Nations where he continues to reside. His practice includes visual art, writing, MC, workshop facilitator, drag performance and more. These are all ingrained with strong recurring themes of colonialism, assimilation, skin colour, gender, mental illness, sexuality, climate change, stolen generations, identity as well as critiquing the Eurocentric western idealised structure that each person in so called “Australia” is forced to maintain.