**An ellipsis is a figure of return that isn’t symmetrical***

‘“To live elliptically” is to ask a question rather than formulate an answer; a “shrug” is a rhetorical response to a non-rhetorical question of the body – an embodied letting go of future promises in favor of life in the durative present’.1

— Darren Byler

Part I: Ellipsis, or a way in

In his 2012 review Walking Around in Lauren Berlant’s Elliptical Life, Darren Byler describes Berlant’s conceptualisation of the ellipsis as ‘a conceptual grammar drawn from psychoanalysis’; a figuring that allows for ways back into life and the durative present through processes of dissociation.^2 Byler describes the ellipsis as ‘work that is trained at scenes of social [...] lostness, the precariousness of life at large’.^3 The word that I have omitted from Byler’s description — in order to present most but not all of an original quotation — is abandonment. It is the word I have chosen to replace with an ellipsis inside a bracket. It is a coupling that not only references certain formal uses of the ellipsis, but also pays tribute to the classicist Anne Carson’s honouring of the lack that a bracket implies, not so much as a site of loss but as a spaciousness that allows for ‘imaginal adventure.’4 Through the pairing of the ellipsis and the bracket I have literally abandoned abandonment, a double negative that reaches through lessons learnt in high school maths class to redress what is meant by its positive outcome — its ramifications within a life. The three dots of the ellipsis exist at the beginning, end or part-way through a sentence or body of text to provide such contradictory functions as the truncating or omission of certain facts or truths, as well as the extending upon or signalling to the rest of an idea or thought. In this way, ellipses are placeholders for the rest of the story. They are pictures within pictures.

[...]

In her recent solo exhibition My Mother’s Labour, Darcey Bella Arnold opens her practice up to processes of elliptical communion, both in the sense of the show’s content and in the way audiences are prompted to read in and around its’ numerous presences and absences. The formal concerns of this exhibition are elliptical where they work towards representations of broader familial narratives, while also acting as veneers capable of obstructing or masking over them. Arnold’s role as an artist opens up to other non-monetary forms of labour — namely the work she shares with her three siblings and father — as a caregiver for her mother Jen, who acquired a brain injury as a result of a viral infection post-cancer treatment thirteen years ago. In this exhibition Arnold re-presents and re-positions a site that is central to her practice — that of the domestic Australian home, which in her case is a place of feminist creation and artistic subjecthood — via an asymmetrical return to the labours of care and maintenance that see the child occupying the role of mother. As Arnold writes in her anecdotal essay that accompanies the show, ‘sometimes I feel I am in a constant state of adolesence when I lost Jen as a traditional mother.’5 The established roles of mother/child have been inverted out of a necessity for survival, as well as by a perceived reverse chronology where Jen believes she is living as her twenty-one year old self. The maternal labour to which the exhibition’s title refers can be understood as both Jen’s and Darcey’s.

For this, her first exhibition with Sutton Gallery, Arnold has created a suite of materially pared-back subsets of paintings consisting of one-to-one and upscaled renders on board and upholstery fabrics. Three apparent groupings of work are demarcated through the orchestration of individual but interrelated formal attributes, consolidated by their specific placement within the gallery. The works can be read as a poetics of space staged across three intervals of exterior, interior and dialogic architecture. During a conversation between Arnold and myself in the presence of the works, she tells me she is allured by juxtapositions in art-making, at which point I become more attuned to the ways these works situate a series of affecting contrasts between public and private, personal and political. Through new explorations in contiguity (that is, through the border-play of visual and anecdotal motifs), Arnold brings her iconic brick paintings into conversation with new directions in mimetic painting.

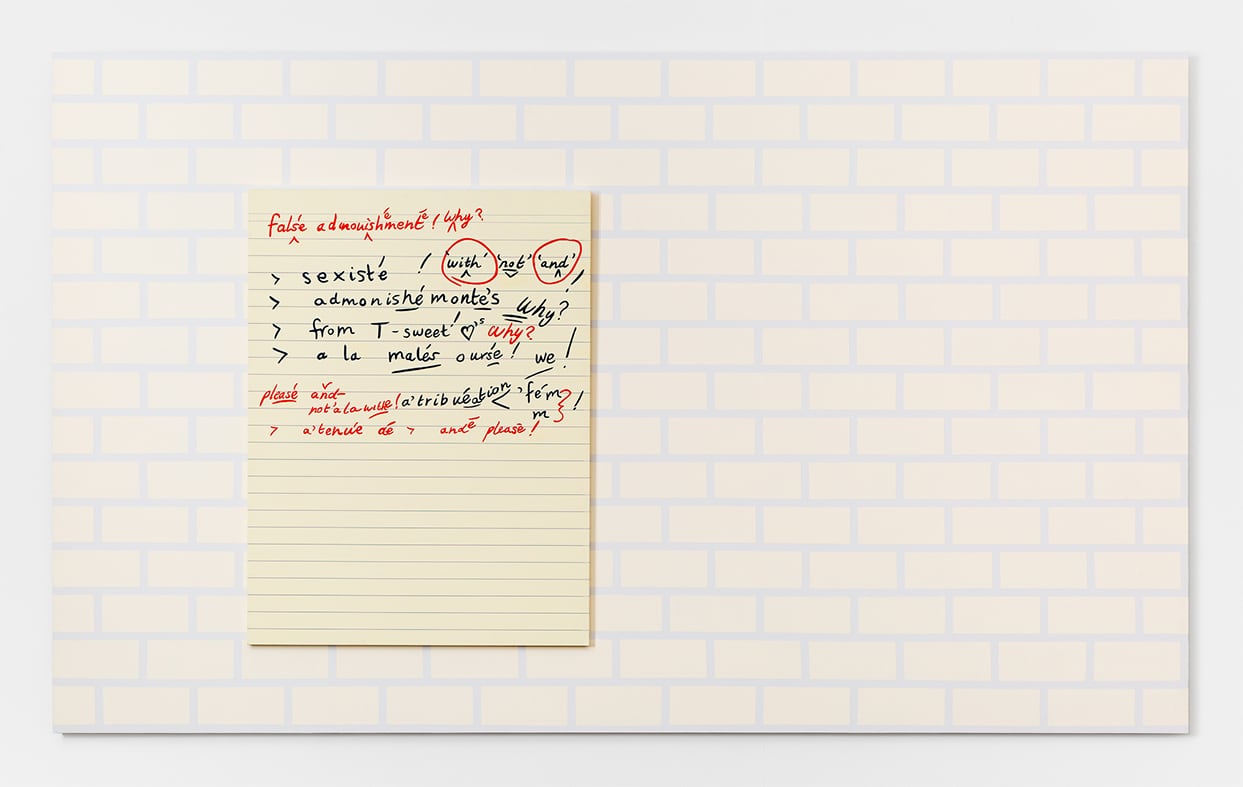

During our conversation, Arnold shows me an image of a Spirax sketch pad, one of many that can be found within the family home in Carlton. The book is covered entirely in Jen’s loquacious hand-writing, a frenetic mass of words and diacritic marks that can be thought of as marginalia that knows no borders. This idiosyncratic writing and word correction approach — which is dotted through the exhibition’s accompanying essay There’s nothing wrong with drinking tea: Disability, memory and language, written by Darcey and edited by Jen — has become a form of therapy for Jen. Increases in this activity can be observed when there are notable shifts in her medication. The family understand this writing to be a combination of English and French, a kind of cognitive blurring that they attribute to her earlier life’s work as a high school humanities teacher and high school student of French previous to that.

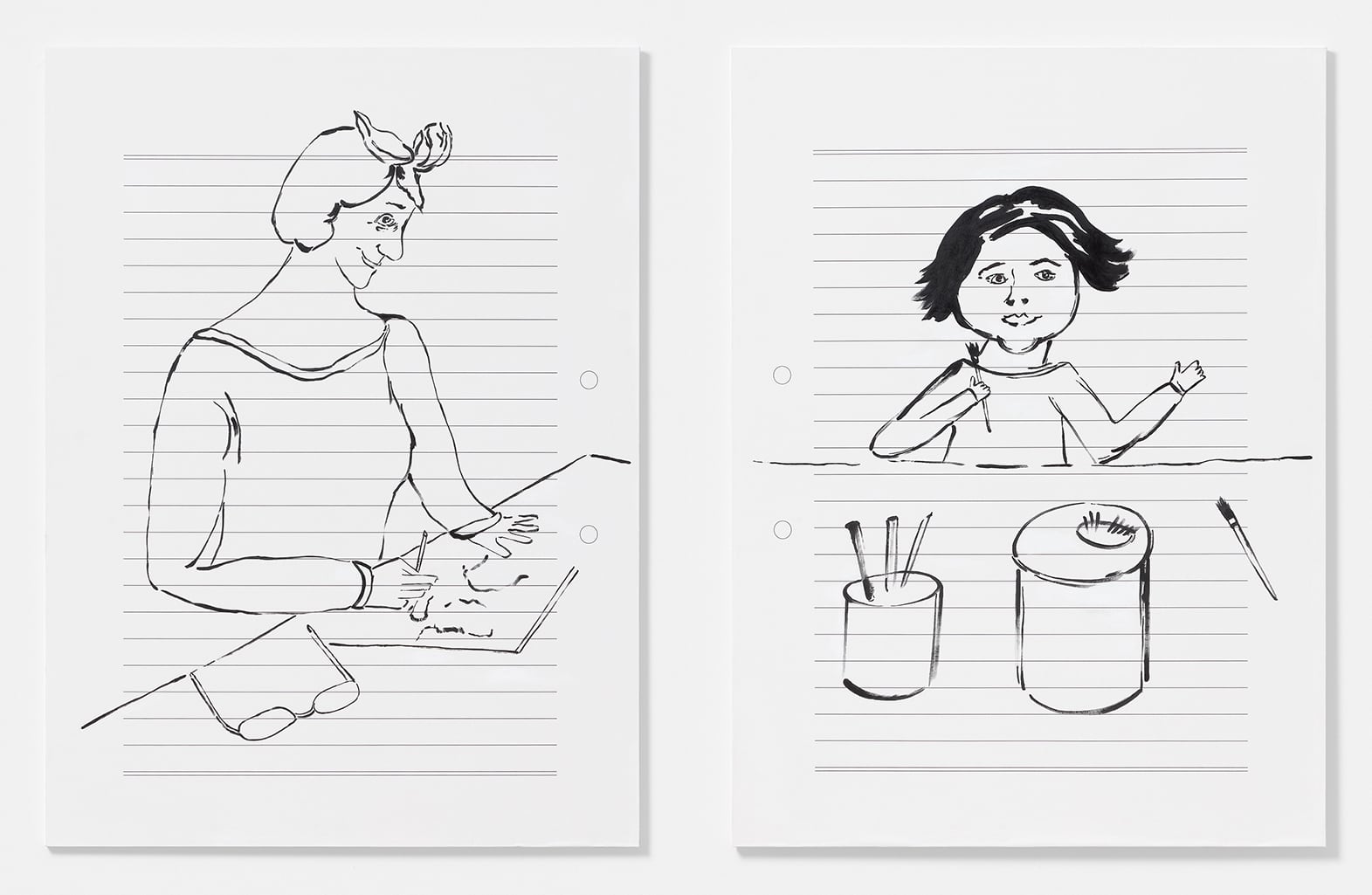

Paintings such as Bella and Coco (both 2018) which Arnold has reproduced from two of her mother’s many quick sketches, as well as the text painting I’ll know my song well before I start singing (2018), are redolent of a generation of artists such as Laura Owen and Jana Schröder who are producing larger-than-life renders of digital and analogue pages, most often in paint. The work of these artists often incorporates signifying features such as grids, lines and digital cancellation signs (erasures) that can be seen to both prop-up and expel the authorial conceits of the individual creator. These works are born out of a proximity to the vernacular of their design, where the proliferation of the raw materials of information flow are everywhere. This attention to proximity is true also of My Mother’s Labour, in terms of where Arnold draws her material for this exhibition from. Where there has been a consistent trajectory of domestic architectural features in Arnold’s work over the past few years, the general premise of this show moves beyond the exterior of the facade to speak to the domestic subjectivities that exist beyond them.

There seem to be veils, upon veils, upon veils here. Where is the original surface?6

— Anne Carson

I can’t help but think of Arnold’s paintings in this exhibition as renders, a term that by one definition describes a cladding that acts to veil or cover over (protect but also conceal) a brick wall. In Carson’s performance lecture Cassandra Float Can, veils are used as metaphors to describe the tricks of language that occur at the edges of a text during the process of its translation. Between the mortar cladding of the brick work and the linguistic veils of Jen’s recombinant mis-translations, this exhibition says something about what Susan Howe describes as the ‘mystic separation between poetic vision and ordinary living.’7 Rather than focusing on the separation of these conditions, My Mother’s Labour positions them within the durative present of the family home, the site that we learn is Arnold’s mother’s most important and prided creative work. While this show communicates something fundamental about the protective yet homogenising tendencies of classic facades of the familiar Australian brick home, it also opens up to the intricacies of these realities with a sincere vulnerability and stoicism.

The moored presence of the brick paintings throughout, particularly as a direct support for the work I’ll know my song well before I start singing, function as an anchor and a reminder of certain normative gender roles within domestic spaces. Arnold explains to me that the title of this work has been lifted from the lyrics of a Bob Dylan song A Hard Rain's a Gonna Fall. It has been used anecdotally in honour of her mother’s astounding capacity for musical recall, despite her disability affecting other parts of her memory which provide contextual information, such as who sings the song and how music is played back to us. In addition, Arnold sees the phrase as bearing relation to the ways that women are forced, through a lack of opportunity and visibility, to have to speak up for themselves and often by means of repetition. With words and passages such as admonishé, sexisté and ‘with’ not ‘and’, there are few but powerful clues to suggest what Arnold informs me Jen’s note to her is about - it was written during a conversation between the two when Darcey was moving in with her current boyfriend. While there are signs of the love that each of the women share for the men in their life, the note urges an awareness of the roles that women assume within the home.

[...]

Part II: There’s nothing wrong with drinking tea

‘show your work—show it again

keep the contemporaryartmuseum groovy

keep the home fires burning’.8

— Mierle Laderman Ukeles

While Arnold can trace a general impulse of familial labour in her work to her 2016 solo exhibition Cat cracker (or catalytic cracker), her work generally takes a more formalist and objective approach to issues of feminism, labour and the built-environment. My Mother’s Labour is the first time Arnold has drawn upon her immediate experiences of making art while simultaneously caring for her mother. With this exhibition, Arnold can be situated within a tradition of artists such as Mierle Laderman Ukeles and Ruth O’Leary who critique and redefine definitions of what it is to make art alongside the pragmatic realities of being a caregiver. A claim for a revolutionary impulse of durative labour was made by Ukeles in her Manifesto for Maintenance Art, 1969. In it she called for a realignment of the value of labour performance, namely the maintenance of care work across domestic and public sectors — such as parenting and waste-management — that is mostly left in the hands of women. Rather than pushing for this largely invisible work to be made visible, Ukeles advocates for Maintenance Art as a mode of creation that is precisely against the productive labour drives of capitalism. Works that are made within this tradition — one local example being O’Leary’s recent performance piece MILK and TEARS at Melbourne’s Pavement Projects — are deeply politicised activities that are deliberately non-productive in their movement away from the aggrandising of the self (which Ukeles describes as the life-drive of creation and development), towards the reinscribing of the death-drive as a site of sustained creation.9 It is what Lisa Baraitser describes as ‘the lateral time of ongo’; the work that keeps material objects and social communities alive.^10 In Arnold’s case, while maintenance is a practice of keeping her mother physically sustained and alive, it also relates to how the family engage memory and language games in order to keep Jen in communion, to keep her in English. They fear that her natural impulse will be to increase communication through her particular blend of English and French.

Part III: Comfort [...] is only easy as a consequence of other people’s labour

A decision as seemingly insignificant as omitting the word abandonment from Berlant’s elliptical thought experiment ealier on allows me to take advantage of the flexibility of the elliptical tool and to open the story up to other interpretations. By doing so, I call upon the ellipsis to invert (through omission) the ways that we may think of loss, not as predicated on or synonymous with abandonment but as a space of optimism. Such a seemingly insignificant gesture is on par with the ways that Jen brings certain contractions of words back into the present — where, for example, disability becomes disableity and university becomes universéity. While we read these alterations as examples of improper grammar, the basic logic of the amendments remain intact. Such anarchitectures (to borrow the term from Gordon Matta-Clark) are a way of opening spaces and sites of cognition up to the possibility that empathic understandings of otherness may be gained through conditions of loss. The potential for optimism to result from loss is analogous to Amy Spiers’ discussion of Sara Ahmed’s queer politics of discomfort as ‘an opportunity, a hope, and a promise to imagine a world that is gathered differently.’11 Spiers notes that according to Ahmed, ‘we tend to feel norms more acutely when we do not quite inhabit them [...] the availability of comfort for some bodies may depend on the labour of others.’^12

Through dissociative processes of loss, abandonment can be repositioned as an opportunity for new kinds of continuity — for processes of staying with. It is something that Byler speaks about in the ‘making space for others [as] described as "an ethical intuition, a caring-for, without the promise of a future.”’13 It is in this space of an unpromised future — of what Baraitser elaborates upon in her research on the temporalities of what many have come to refer to as stuck time or continuous time14 — that we can situate the ellipsis as the circuitry of the here and now. A revolutionary function of the durative present to which My Mother’s Labour belongs.

Abbra Kotlarczyk is an artist, writer and editor living in Naarm, Melbourne.

*Lauren Berlant, Lauren Berlant discusses “reading with” and her recent work, Artforum, January 30, 2014. Accessed September 4, 2018.

14 Baraitser, op. cit.