Curator: Kimberley Moulton

Artists: Joi Arcand (Muskeg Lake Cree Nation, Canada), Megan Cope (Quandamooka), Kirsten Lyttle ( Waikato, Tainui A Whiro, Ngaati Tahinga, NZ (Melbourne based)), Vicki Couzens (Kirrae Wurrong), Lisa Hilli (Makurategete Vunatarai (clan) Tolai / Gunantuna people of Papua New Guinea) and Nakia Cadd.

If you have ever had the experience of sitting in a circle with others, all hands together weaving, sewing or engaged in some kind of making, you will would know about the particular moment of transition from conscious focus. Our bodies, particularly the tips of our fingers, become familiar, attuned and sensitive to where the fibres wish to bend; there is no need for force. As we continue to work we become open to the others we are with. We begin to listen and listen deeply. We begin to speak and speak openly and honestly. Sometimes it is only when this flow is interrupted that we realise the importance of the space we conjured together. Octopus 18: Mother Tongue, curated by Kimberley Moulton, feels like this space; a binding of threads that wish to be woven together. Joi Acrand, Vicki Couzens, Kirsten Little, Lisa Hilli, Megan Cope, and Nakia Cadd congregate to recognise each other’s specific Indigenous sovereignties and that of the Woi Wurrung whose land they gather on.

The first work we meet is Here on Future Earth (2009) by Joi Arcand of Muskeg Lake Cree Nation, Saskatchewan, Treaty 6 Territory. This series of digital prints show the street scapes of a town on Turtle Island. People are going about their day among buildings fitted with signage in Cree language. As Moulton notes in the accompanying essay, this is not a new future but a reinstatement of Cree identity in the landscape. Within these images Cree language dominates. I can’t help but imagine the same treatment applied to streets I know well – the children depicted in these scenes bring home the heart of efforts all over the world to revive languages.

The sound of Kirrae Whurrong language emanates from Vicki Couzens’ possum skin cloak, permeating our skin. These are the words of the possum song. Couzens’ cloak seems to float out from the wall and we are not met with grey fur or even soft treated leather inscribed with the unique stories of the cloak’s owner. These rectangles of skin are dried, hard and cracked. They show the reality of practicing an ethic of reciprocity that is the taking of life from other beings. However, I am quite sure the death of these possums was an accident and their bodies were collected from the side of the road where they fell after being hit by a car. As Moulton suggests, this cloak ‘is like a book with blank pages, ready for the stories to be told and scratched into it.’

For some of us the words our ancestors spoke are not at the tip of our tongue, but the worlds of our languages still exist within us. Exhibitions such as Mother Tongue are vital in the process of reviving these languages. We may have no one to speak to or have some work to do until we gain fluency, but in the meantime we can speak into these spaces and show the many ways we continue to listen.

Turning left from Kooramookyan leerpeen (possum skin cloak song) (2018), towards the direction of the Birrung Marr, is Kirsten Lyttle’s series of photographic and woven works, Tangata Whenua/Not Tangata Whenua (2018). Images derived from the Merri Creek are reformed and woven to reflect Lyttle’s particular place in the world. As witness to these three images we are witness to a practice of walking and contemplation, about this place and a home across the sea. I imagine the process of slicing up photographs and processing plant fibres, ready for weaving, as one and the same. Images of the creek are infused with the colours of our Aboriginal flag – red, yellow and black. The handling of each colour hints at an acknowledgment of their symbolism. Through this work we are invited into Lyttle’s world. We are present at the water’s edge, yet this is not the waterway from which our own life flows. We are here, and through that we are in a position to belong here but not in the same way as Wurundjeri. It is a complex space of constant learning and renegotiation within our own bodies and minds.

Turning to face east towards the hills where yams within protected grasslands grow, I face another photographic work, Lisa Hilli’s In a bind (2018). A woman stands in a lush green forest, her face thickly wrapped and entirely obscured by string. She has no mouth, no eyes, no features to recognise. This works speaks to both the gaze of the coloniser and the complicated internal world of anyone who has experienced the attempted denial of language, culture and kinship through various colonial mechanisms. Hilli, with Julia Mage’au Gray and Sunameke, also contributes the video work Identify Me (2016). A gilded frame that would generally enclose static depictions of people and land is engulfed by a landscape. A woman stands not so much within the frame as on top of it. Her stance and facial expression are defiant; ‘identify me if you dare’. Her attire is tangled around her body in a way that restricts movement and we witness the moment she unravels centuries of the colonial gaze to take control of her image and to assert her sovereignty. Within the context of this exhibition Hilli leads me to consider my own ability – as someone from elsewhere – to speak with Woi Wurrung with their words and on their terms.

On the opposite wall is another large projection, Megan Cope’s work Bummeira (2018). This word from Jandai Language is the first name of Brown Lake, Minjerribah (Stradbroke Island). The English characters that signify the word Bummeira sit in the space with a view into Quandamooka country. The scale of this work gives the impression that one could step into it and exist for a while, emphasising the reality this work is asserting: that this is where we already exist all the time. We exist in places known by names they have had forever and names that are new. In the accompanying essay Moulton writes that ‘…the absence of fluency within the landscape and the curriculum makes visible the attempt to destroy that cultural connection.’ As Cope make these old names visible she asserts Indigenous sovereignties, revealing the extent of the damage caused by colonial occupation. This deadly combination has much therapeutic value.

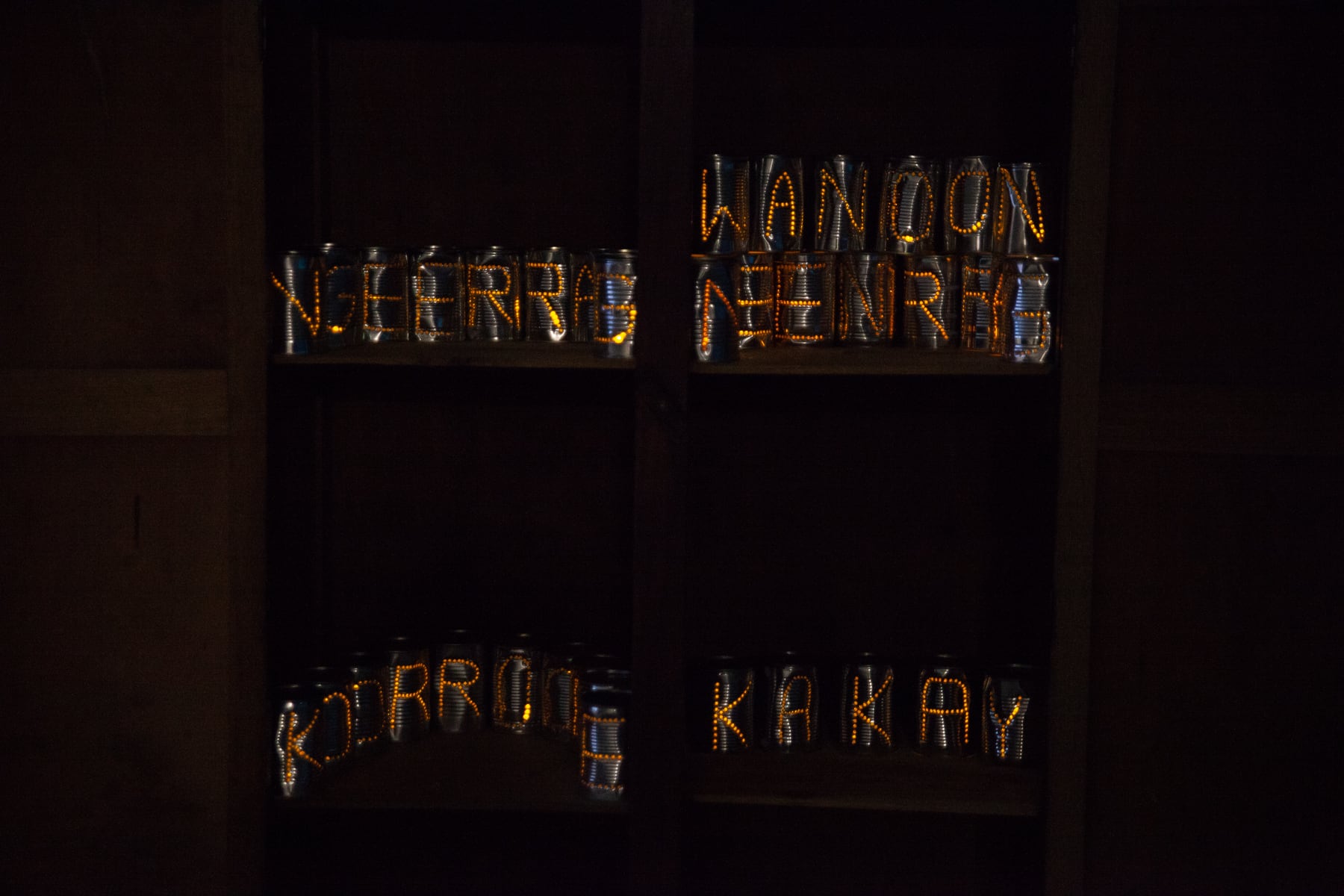

With Cope at her left shoulder and Hilli at her right is Nakia Cadd and her work Korrookee (grandmother), Ngeerrang (Mother), WanoonNgeerrang (Aunty), Kakay (sister) (2018). An old timber pantry cupboard is lined with tins. Once filled with food, they are now illuminated by tealight candles which shine the words Korrookee, Ngeerrang, Wanoon Ngeerrang and Kakay out into the darkened space. This work is derived from a Stolen Generations story particular to Cadd’s own family, where her Korrookee devised a way to convince the welfare not to take her children away. Cadd explains that ‘to make sure that didn’t happen, grandma Mary would trick them to thinking the cupboards were full, by reusing the cans and filling them up.’ Nakia’s work personalises this collective history, showing that it was the actions of individuals that often made the difference between surviving the child removal policies and experiencing the worst of it. This is a history that is not over yet – we still hurt deeply but continue to work to make sure our families are safe, strong and happy. Nakia shares in her biography that she is looking forward to seeing how motherhood influences her work. So am I.

It is worth noting that there are still Indigenous people in this country who would look at the entrance to Gertrude Contemporary and assume that they are not welcome there. Having said that, this exhibition is part of a long-term collective effort, within the arts and other spheres, to weave Indigenous sovereignties into our everyday lives. This exhibition is a solid example of this, using the gallery space as an interruption that allows us to revisit the threads that make up our DNA. All the while, it also addresses another ‘health gap’ that exists within the non-Indigenous population’s relationship to Indigenous sovereignties.

Because of this exhibition and the opportunity to write about it here, I had a chance to wonder how our linguistic landscape will grow and morph as languages are revived and shared across Australia. I imagine a future that is multi-lingual and with this fact home to multiple sovereignties, not only recognised but embodied by all who live here. I had a chance to feel threads we carry as Indigenous women and imagine the threads that will form through lifetimes lived on Indigenous lands, whether we are Indigenous or not.

Katie West is a Yindjibarndi woman and artist living and working in Narrm, Melbourne.