Artists: Ander Rennick, Annie Wu, Bette Gordon, Catherine Flora Murray, Kathy Acker, Keith Lafuente, Kiki Ando, Hana Shimada, Jim Singline, Laura/Deanna Fanning, Lauren Kerjan, Lucreccia Quintanilla, Maison the Faux, Megan Hanson, Nox with Michel Henritzi, Selby Nimrod, Simonne Goran, Terence Sellers, Women’s History Museum and Zhuxuan He.

Curators: Rafaela Pandolfini with Ainslie Templeton.

Session Vessels, curated by Rafaela Pandolfini with Ainslie Templeton, features the work of twenty artists and collectives from Australia and the USA, spread across all four galleries of AIRspace Projects, on Eora Nation country in Sydney’s inner west.

Bodies

I enter the front gallery space of Airspace Projects and am surrounded by bodies; mostly mannequins but virtual bodies, too.

‘…it loves without condition or discrimination, but only once the material labour of its construction has been dismissed.’ (2018) is a video work created by Megan Hanson during the exhibition opening. Dressed in a very large black bow that now lies on the gallery floor in front of the screen, Hanson moved around the space making a livestream video and sipping wine. The video features the bodies (excluding Hanson’s) that were in the room at the opening: some pose and perform, others smile enthusiastically ‘for the camera’. Overwhelmingly, though, people film and take pictures of Hanson as she films them. The reflexivity of the work serves to highlight the increasing circularity and fluidity between the real and the virtual, and the power relations of watching and being watched.

The emphasis on the body as site is evident in the number of fashion designers in Session Vessels, including Keith Lafuente, Ander Rennick, Maison the Faux, amongst others. The horizonal colour gradient of Zhuxuan He’s Untitled (2016) catches my eye. The silk organza dress stretches from red through yellow to white, it’s shape and structure drawn from the folds of honeycomb-style paper lanterns.

Most notably amongst them, though, is the New York collective Women’s History Museum. Established by duo Amanda McGowan and Rivkah Barringer, Women’s History Museum creates clothing driven by explicitly feminist motivations. The name of their collective forms a ‘sincere joke’ simultaneously critiquing the museum as an immoral place filled with elitism and theft and its status as a container for ideas. Drawing on historical images of women, Orange peel fugitive purple optical dress (2018) looks a bit like a Victorian era puffy skirt and bodice; through screen-printing and a cut-up technique it is recast as a grungy, deconstructed garment. For Women’s History Museum, clothing is a form of resistance.

Space

Gallery Two presents work by Rafaela Pandolfini, who curated the exhibition with Ainslie Templeton. Pandolfini’s work A Minor History of the Feminine (2018) includes a short text of personal anecdotes and observations, some exploring sexuality. This text sits next to a series of ceramic vessels and a cushion that is twisted and painted to resemble an anus. Fabric printed to look like Chux cleaning cloths cover the table, a motif that appears throughout the exhibition.

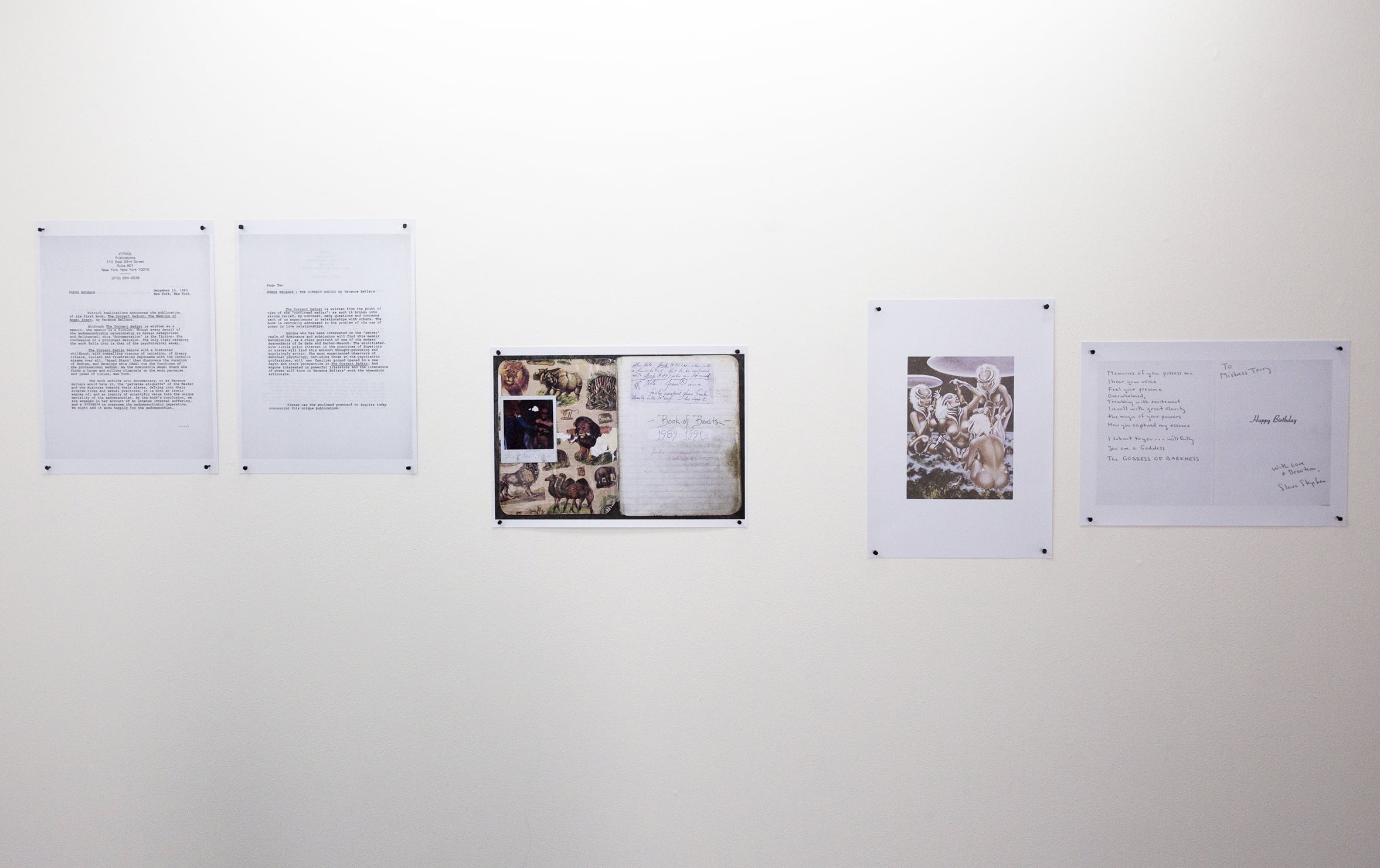

Further into the gallery, documentation from a Master’s exhibition curated by Selby Nimrod at Bard College in New York is affixed to the wall. Titled Measures of Authority (2018), the exhibition featured photographs and documents by Terence Sellers, and artwork by Chris Kraus and Leigh Ledare. An adjoining wall displays documentation of a press release for The Correct Sadist, a 1985 book by Terence Sellers. The book explores BDSM, as much of Sellers’ work did - there is also a personal note to Sellers by ‘Slave Stephen’.

The inclusion of this documentation functions to bring these important, and currently very hot, 1980s artists and thinkers into conversation with artwork by local emerging artists.

Aura & Homage

‘I know what you mean about slipping roles: I love it, going high low, power helpless even captive, male female, all over the place, space totally together and brain-sharp’.1

-- From I am very into you, Kathy Acker and McKenzie Wark’s series of email exchanges from 1995-96 published by Semiotext(e) (2015)

Galleries Three + Four of Session Vessels form a homage to legendary feminist and poet Kathy Acker. Acker claimed her sexuality with rawness and aggression in the late 1970s-80s New York Downtown literary scene. With the release of Kraus’ biography of Acker in 2017 many, including myself, have recently read Acker’s work, discovering her punk energy for ourselves. Both these women’s names – Acker and Kraus – exude an aura; they are leaders of different moment when (white) feminists found their voices and spoke honestly about their sexuality. Acker’s work blurs the distinction between the real and fantasy - a tactic that Kraus is also known for - leaving the reader entangled not just in her writing, but also in her personal narrative. This ambiguity leads us to reconsider the boundaries between fiction and fact, and how distinct those boundaries ever where to begin with.

One of the gallery spaces features Love, Emily (1987), a sound recording where Acker reads from My Death, My Life by Pier Paolo Pasolini, with noise accompaniments. Love, Emily is the only work in an arguably tricky space; it plays through speakers without headphones and much of the detail seems to get lost. The final gallery features the film Variety (1983), which was produced by Bette Gordon with the script written by Acker. Unfortunately, there is no seat in the space and light streams into the room from the entrance, making it hard to concentrate on the video; I only watch for about five minutes.

I wonder about the inclusion of Variety and Love, Emily in the exhibition, given their presentation makes them tricky to view. But Acker’s work is undeniably important; it zeros in on a particular imagining of feminism, queerness, and fluidity of forms and categories with such strength that she is a source of inspiration for so many artists, women and female-identifying people.

Explanations

There is no blurb or contextualising information for Session Vessels; I like this immensely. It creates a situation where intention is swiftly replaced by interpretation.

Kathleen Linn is a Sydney-based emerging writer and curator.