When an artist uses new materials, techniques or technologies in their practice, the conventions of experience and analysis are inevitably destablised for the audience. Regardless of whether the innovations are new to human knowledge or simply new to the artist, the shield of expectation – I know what to expect from this painting/from this play/from this piece of music – becomes critically perforated when we encounter a fresh approach to art-making. The controversies of modern art are easily understood in this way, since with this newness comes both a refusal of tradition (by the artist) and a loss of how to measure the achievements of the work in relation to all that has come before (for the audience).

Jess Johnson and Simon Ward’s exhibition Terminus at the National Gallery of Australia confounds the expectations of the audience on several levels and dimensions, enveloping the visitor in a multipart virtual-reality (VR) journey through a world of patterns, colours, shifting perspectives and perplexing beings. Bridging the spheres of participatory art, video art, immersive installation and two-dimensional drawing, Terminus is a very fetching conceptual experience. It also poses a number of valuable enquiries concerning how the myriad potentials of emerging technology will transform our museum spaces.

The harnessing of VR technology by Johnson and Ward was unleashed on the public in 2015 with the exhibition Wurm Haus at the National Gallery of Victoria in Narrm/Melbourne. That show signaled a development in the collaborative dynamic of Johnson and Ward, which had begun a couple of years before when the two were linked up by a mutual friend. Ward, who has a background in film, proposed animating Johnson’s intricate drawings, leading to an ongoing creative relationship – no small feat given Johnson’s view of art, up to this point, was a determinedly solitary activity. With the launch of the Oculus Rift ‘development kit’ headsets in 2014, anticipating the general release of the company’s virtual reality headsets in 2016, the pair then began work on their first VR piece Ixian Gate (2015).

What this story of an emerging collaboration and evolving creative process reveals is that the use of new technology in Terminus is not a gratuitous exploitation of contemporary computational devices just for the sake of it; rather, it is an elegant, almost cosmic, exploration of unfolding horizons in creativity and technology. As Johnson notes, ‘it felt like the most natural thing in the world’. Describing the experience of first seeing her drawings as animations, she states: ‘it was like experiencing something that had already existed.’

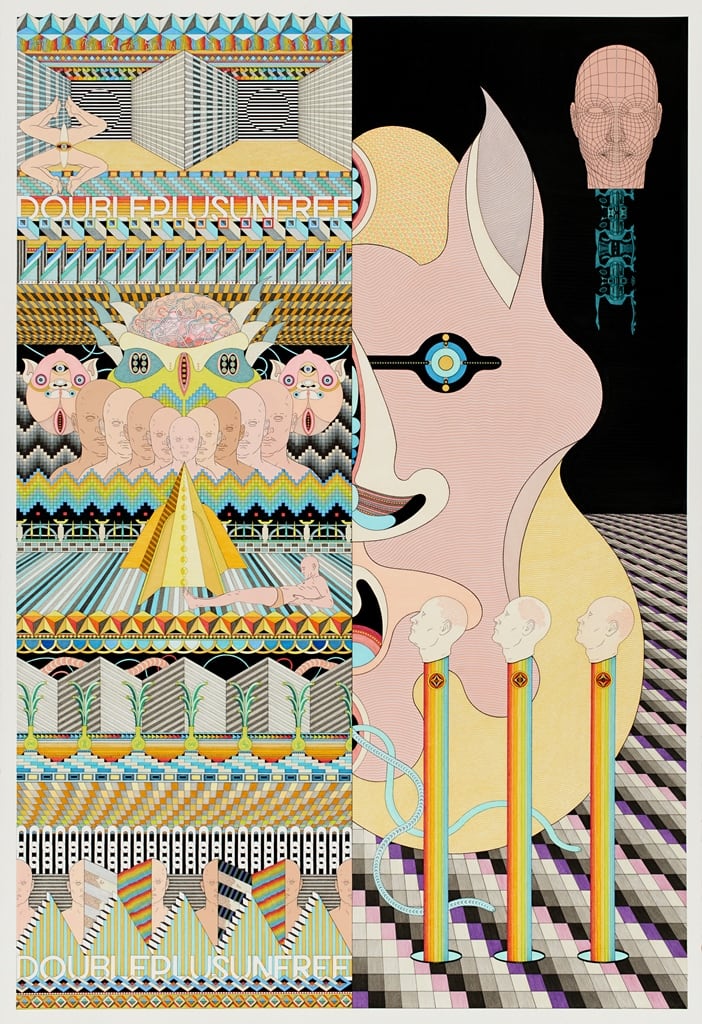

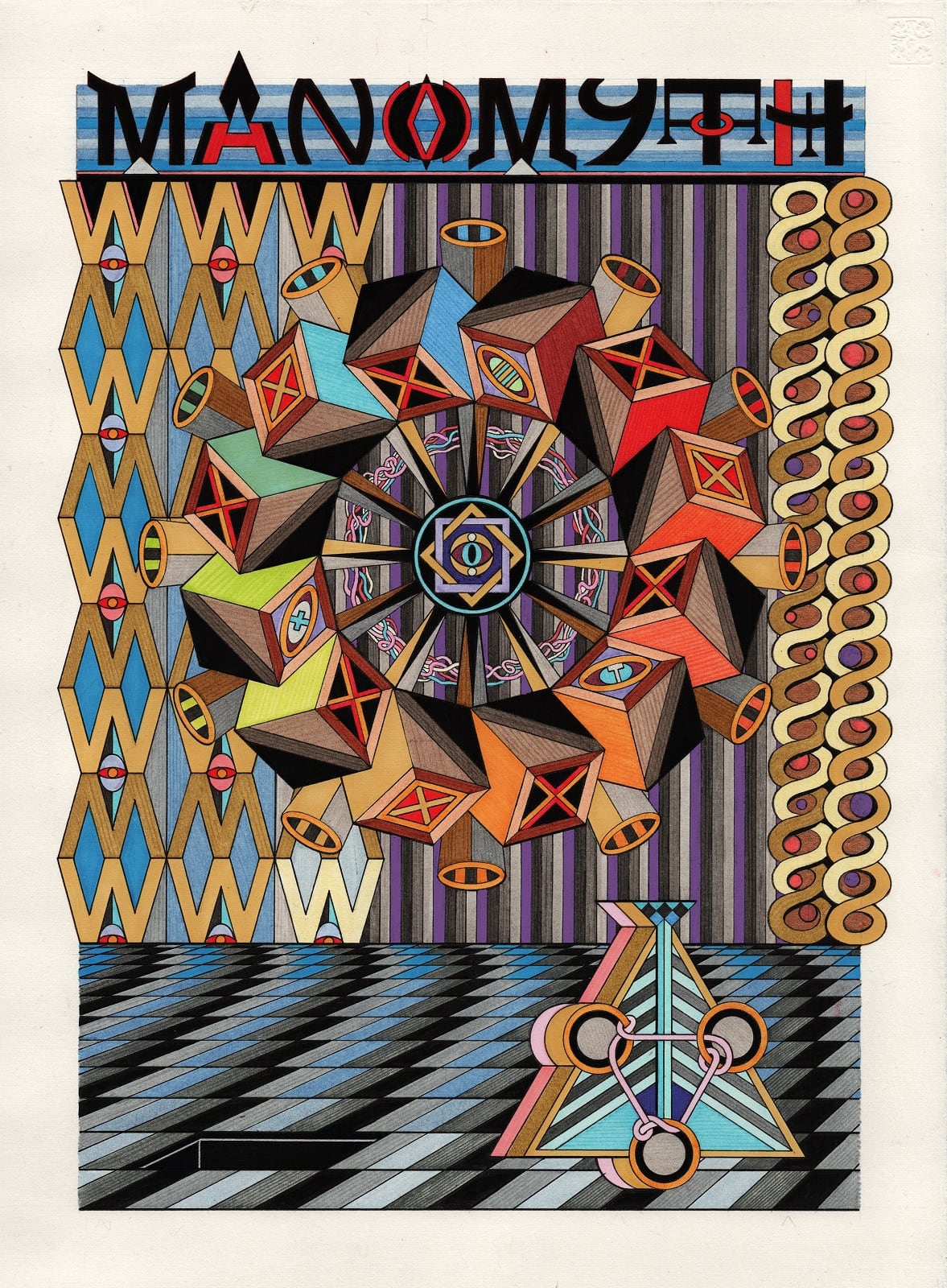

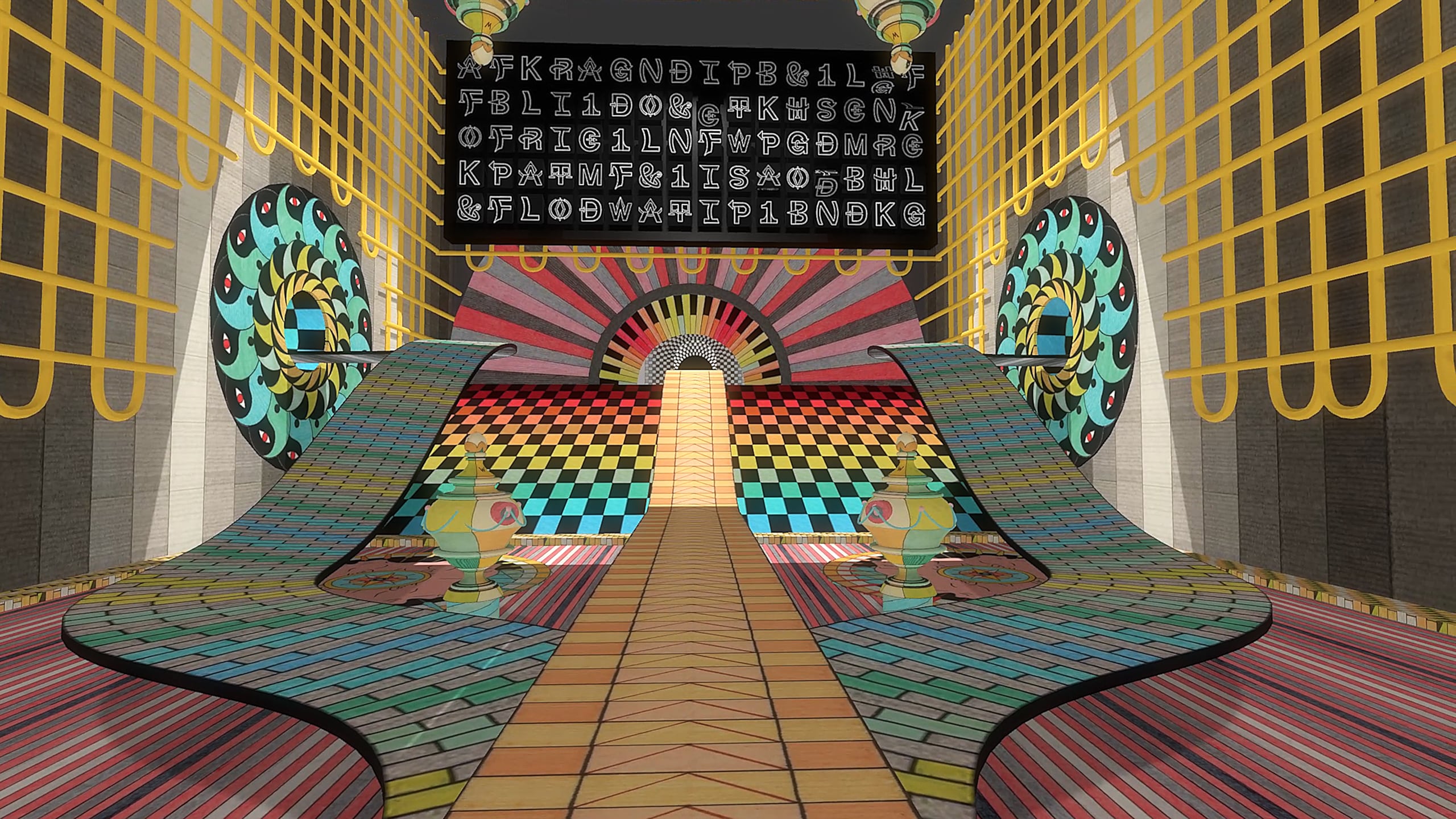

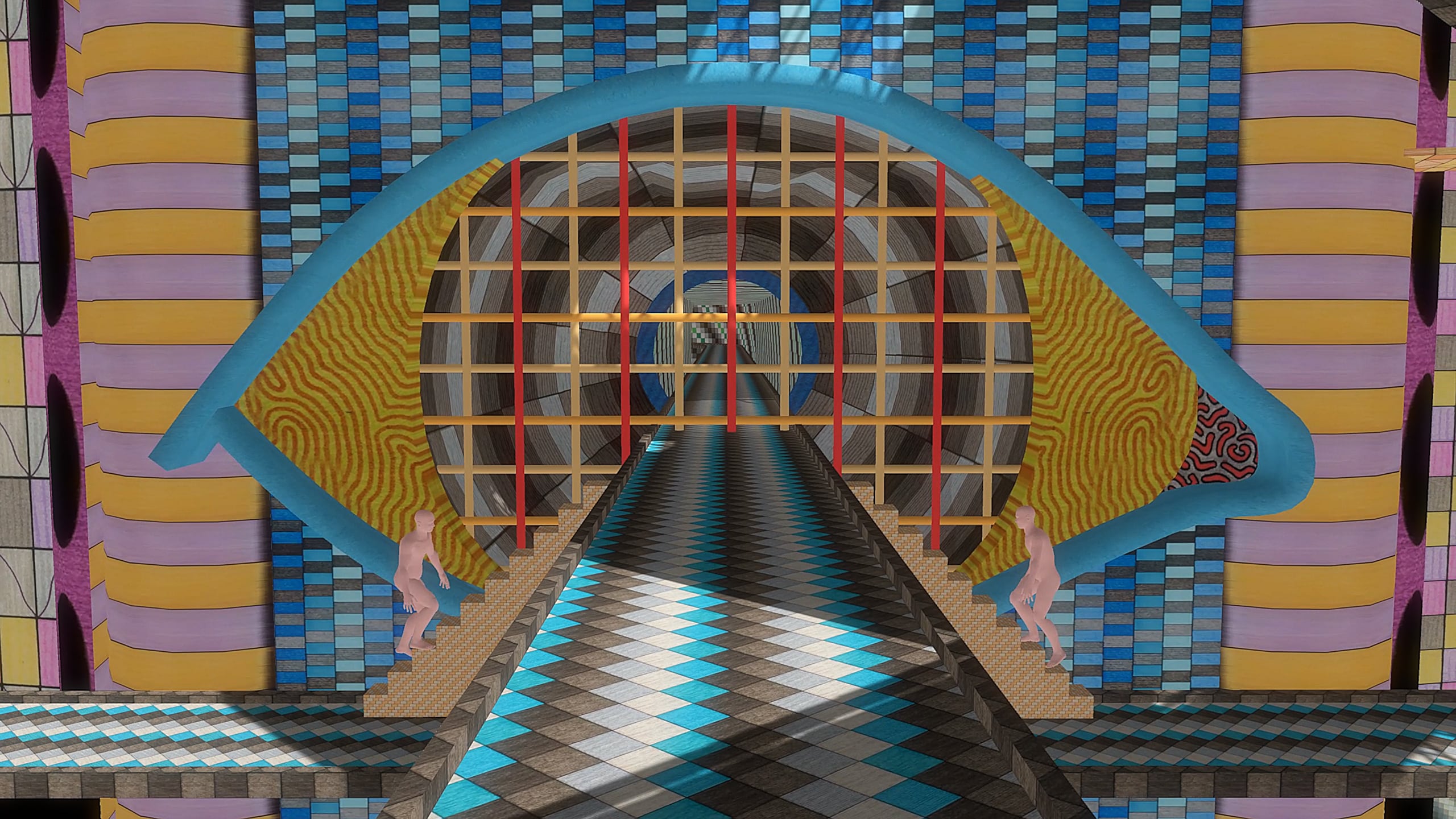

Terminus comprises five virtual reality stations that lead the visitor through an aggregating journey into a world that Johnson has been imagining, experiencing and drawing throughout her career. As soon as the visitor dons one of the headsets in the gallery, the two dimensions that had been previously on the pages of the artist’s drawings become three dimensions that, in turn, affect the three dimensions of the viewer’s existence. In J. G. Ballard’s novel Cocaine Nights (1996), a character muses on what it would be like to live within the ‘strange etchings’ of eighteenth-century Italian artist Piranesi (1720-78), to be tangled in lines and staircases. A similar imagining is realised in the VR works of Johnson and Ward, which launch the audience into existing drawings and newly conceived spaces. The audience member has some agency as a participant in these spaces, able to direct their gaze around as they proceed, personalising their experience. But the temporal patterns and pathways of the journeys in Terminus are out of the participant’s control. This enforced restraint is most pronounced at points of close contact with gleaming projectiles, portions of rapid incline or descent, and the sense of imminent disaster that might transpire if you are taken too close to a precipice.

In the second stage of the five-part journey, title Known Unknown (2018), you find yourself sitting on a plinth inside a magnificently coloured, highly geometric environment. A large, classical temple stands nearby, announcing above its portico not the graphic tales of great gods and heroes, but the words: ‘The rats who build the labyrinth from which they plan to escape’. Perspective is then mutated before your eyes as a small version of the temple emerges and raises you, by contrast, to the stature of a giant. This sort of seamless metamorphosis is a repeated theme in the works of Terminus; the environment enclosed in the Oculus Rift headsets is constantly unveiling itself, gesturing towards an organic, breathing property in the world Johnson has conceived. And while this built environment is continually transforming without noticeable intervention, the figures and creatures that inhabit the environment alongside the participant are fleshy but lifeless. It is a peculiar, counterintuitive place to inhabit.

Alongside the visual journey in Terminus is a pert, synthesised soundtrack evocative of 8-bit computer music by Andrew Clarke. For Johnson this soundtrack contributes an emotional dimension to the creation of the final, collaborative work of art: ‘he creates unique stories through his music … he creates his own journey.’ When considering the use of new technologies by artists in the future it is fitting to think about how collaboration between different creatives and technicians might feature more prominently in art practices. Johnson has also noted that the VR environment the audience encounters in Terminus is not the product of simply a filmmaker animating her creative works. It is the product of equal cooperation between herself and Ward, ‘there is as much Simon in the world as me.’

Certain logistical issues are important to bear in mind when thinking about the future of new media platforms in our museums and galleries. For example, how do you ensure that the audience is not ripped unceremoniously from the virtual reality space when they remove their headsets, particularly when the work sits in a series or unified exhibition. Terminus sidesteps this pitfall by placing the headsets in a physical gallery environment that visually aligns itself with the virtual reality environment. The gallery space feels like a pared-back exhalation of the space enclosed in the headsets. It is also relevant to consider how logjams might be avoided when using individual headsets in an exhibition, but this did not appear to be a particularly injurious issue in the operation of Terminus. It would appear that people who attend contemporary art exhibitions are, on the whole, happy to wait. Following on from the tumultuous years of the twentieth century, when expectations were shaken by the radical presumptions of ‘modern art’, perhaps weare happy to luxuriate in any mild inconveniences that come with newness and innovation – we are galvinised by the idea of infinite worlds.

Suzanne Fraser is an arts writer, researcher and lecturer based in Narrm/Melbourne. Her PhD investigated the role of colonial art collections in shaping Australian cultural identity. Her current research uses postcolonial theory to analyse digital imperialism in contemporary art practice. She co-authored the report Refuge 2017 Evaluation: Heatwave (2018) on behalf of the Research Unit in Public Cultures and the City of Melbourne.