Alana Hunt: I'm looking to you as a means of engaging with some of my own questions and uncertainties as a non-indigenous artist living in and being increasingly influenced by a community and environment - or perhaps, rather, a world - that is predominately Aboriginal. You and I are on opposite sides of the Kimberley, but in a somewhat similar boat.

Can you tell me about this photo — the mountain(s) with shades of ochre on top. This photo stopped me in my tracks when I first saw it on Instagram. It still does, and I've looked at it a lot. It's beautiful and compelling, but also quite unsettling. From the series Ochre and Light, it is about your two homes in Australia and New Zealand. Can you tell me about the work, and your relationship to these two places?

Katie Breckon: The first draft of this image happened very quickly as an immediate response to standing beneath the majestic Mitre Peak in the Milford Sounds, New Zealand. The idea, however, had been brewing for some time and was born from a feeling of homesickness. Living in the remote West Kimberley and returning home to New Zealand several times a year means I move between two very different worlds, and neither really understands the other.

I grew up in a valley in New Zealand where the sky was long and narrow and although I have travelled extensively, it was not until living in the flat savannah of Derby that the absence of hills and mountains became noticeable and overwhelming. The Kimberley is saturated in sunlight for most of the year. At times the sun and heat feel unrelenting and I long for winter. I began to have a recurring daydream of standing under mountains in the deep south of New Zealand. It was a subconscious retreat to a place I know.

I became interested in ochre through my work at Mowanjum Aboriginal Art & Culture Centre. We have colour charts of Kimberley ochre on the studio walls – it’s a palette that is really different from my homeland. Ngarinyin artists and arts workers harvest ochre and together we produced a short documentary called Ornmol (Ochre) that explored the cultural meanings, associated language and uses of ochre. Ochre is country and when it is used in artwork it symbolises a connection to place.

I have never been a very successful landscape photographer because I am not interested in recording what is visible; instead I want to recreate what I feel. Being on country with Ngarinyin and Worrorra people and hearing their Dreaming stories has drawn me deeper into the land. When you really listen and begin to experience this cultural way of relating to country, there is a sensitivity that develops. It transforms how you see, feel and understand the land.

West Australian author Tim Winton wrote in his book Dirt Music about the red earth staining the skin and soul. I feel a constant push and pull between the two places I call home. Over Mitre Peak I have layered Kimberley ochre, which acts as a stain or filter, symbolising the dichotomy of home and belonging.

AH: When I think of landscape in art in Australia, I arrive straight at the colonial and European currents that shape this discourse, historically and in a contemporary sense. I’ve become somewhat skeptical of any depiction of the ‘landscape’ by non-Indigenous artists—I’m not sure if that is a good way to be, but it is a state I linger in.

When I first moved to Warmun on Gija country in early 2011, I spent six months in the bush there before I travelled back to a city again, where I took a group of artists to Perth for an exhibition. In Gija country I’d been welcomed to every new spring, creek bed or water body I encountered, and was told stories about the hills and plains and stones, almost everything we passed. So when we got to Perth I had this horrible, unsettling feeling of not knowing where I was walking. What stories lay under this cement footpath? What is the name of that creek? Was I allowed to be here? It was a difficult but productive feeling – one that made me realize the importance of walking lightly on this entire country, of which I am an uninvited guest.

Ochre feels, to me, like such a physical embodiment of ‘country’ in an Aboriginal sense that I’m not sure I would be able to use it in my own work. My partner is Miriwoong/Ngaliwurru, and traditionally through marriage I would have certain rights and responsibilities over country, but as a whitefella it doesn’t feel right to exercise that, at least not in the world we live in today. You seem really comfortable working with ochre and employing found artefacts like spearheads in your work, and it comes across quite powerfully. How do you experience the ongoing colonial and racial tensions I’ve touched on, if at all?

KB: My artwork has only recently incorporated subject matter reflecting West Kimberley Aboriginal themes. It is a dominating influence in my life. For many years I was unsure how my work with Mowanjum Aboriginal Art and Culture Centre and my art practice could coexist. As a non-Aboriginal arts worker I felt it was important to filter my experiences in order to protect both the cultural content I was exposed too and my personal creative process. So initially I drew a line between both worlds, and tried to discourage any overlap. I am not sure if this was completely necessary but at the time it felt right. As the years passed and I spent more time out bush and developed deeper relationships the line I drew to divide my worlds began to blur, a natural progression of settling. It started to feel unnatural to keep my creativity under lock. Now I try to remain cautious and respectful, and I interrogate my motivations, but also allow myself the freedom to explore ideas.

Working at the art centre taught me about the cultural protocols for story ownership and storytelling, basically who can speak for what. Understanding this has helped enormously to bring my creative focus back to my personal space: here I am in this remote place and what is my story to tell?

There is poetry to the way ochre literally stains my skin. Ochre is country and that is why I incorporate it in my artwork. I am directly referencing place, identity and deep within that are very personal links to the patient teachers who have shared their culture and stories with me. I initially received permission to use ochre in my artwork from Ngarinyin elder Pansy Nulgit but actually the Mowanjum Arts Community are very relaxed and supportive of non-Aboriginal people using ochre to paint with, although I understand this openness may be different for other communities.

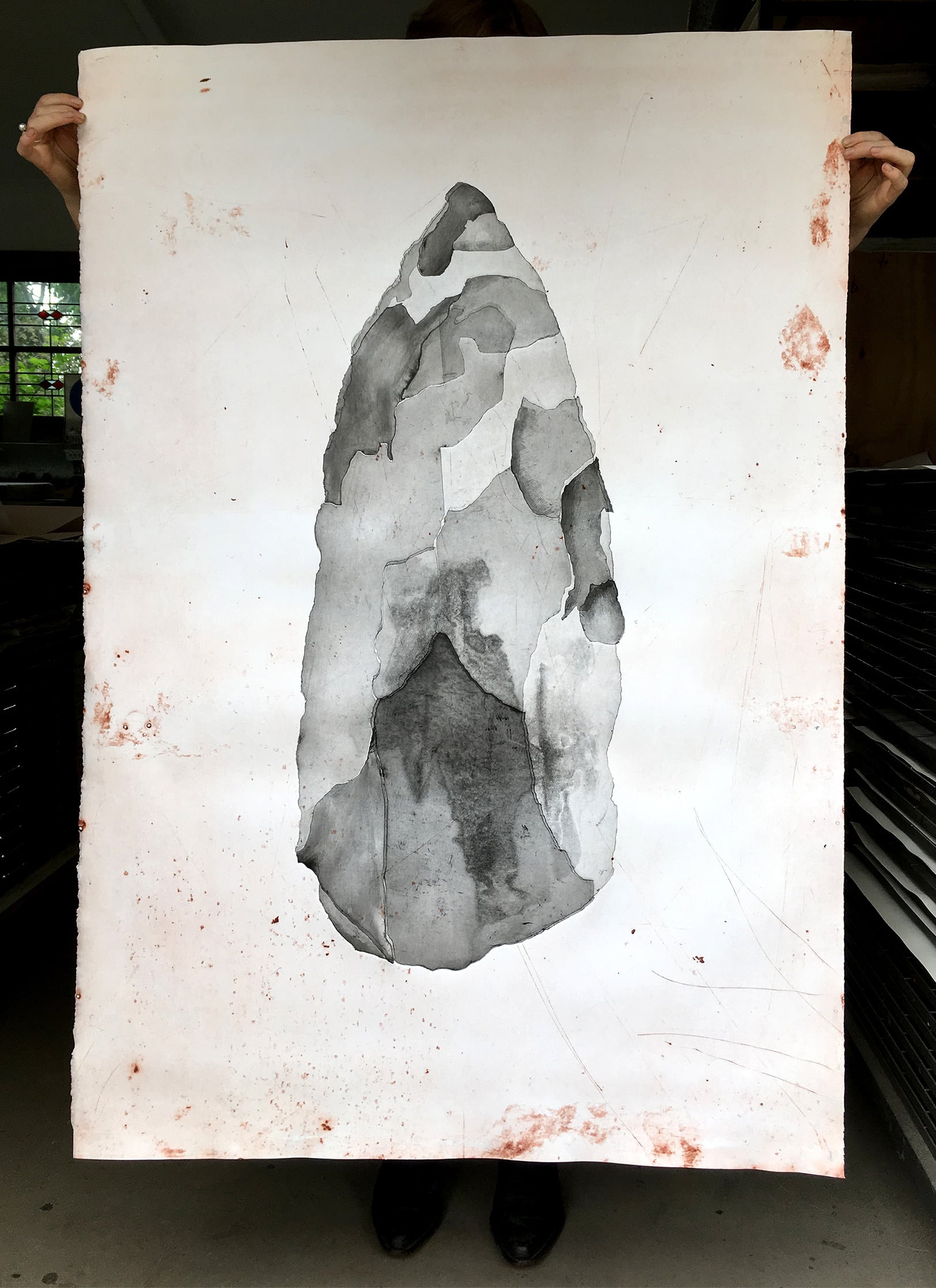

I found the stone tools I’ve been working with on my property when we first bought it. They had been collected from Worrorra Country by crocodile hunter and bushman Vic Cox, whose deceased estate we purchased in 2005. I invited Worrorra elders and friends Janet Oobagooma, Nyorna (Donny) Woolagoodja, anthropologist Kim Doohan and geologist Joh Bornman to view the objects and check for restricted material. Once this process was complete I looked at the pieces more closely, examining the stone and craftsmanship. It turned out that Nyorna Woolagoodja’s father and Vic Cox had been friends and so there was this serendipitous connection between the four of us. Eventually I asked Nyorna whether I could make studies of the tools and he was happy for me to do so. Nyorna is a creative thinker, artist and very supportive of the arts. While I am confident in how this process unfolded, the communication and relationships that are a key part, I suppose how outsiders interpret my work is a lingering anxiety.

AH: Yesterday I saw your Instagram post about the Aboriginal Heritage Act and Vic Cox’s stone tool collection which you’ve been working with. It’s interesting how, in hindsight, we have learnt that it is important to leave cultural artefacts where they are on country in order to more easily prove ‘human activity’, which will ultimately enable an area to be ‘protected’ under Australian law. I wonder, had Vic had known the implications of his collecting, if would he have continued? Perhaps not. I’m always wondering what we are doing today that could have similar—if unintended—ramifications in the future? The answer, I see, is so very much.

KB: Vic Cox was a bowerbird, his impulse to collect was very strong. Vic’s story raises questions about our collecting habits and the western notion to take something for ‘safekeeping’. Disconnecting an object from its original context or community can create gaps in knowledge and jeopardies the protection of cultural sites. This speaks to the importance of collection institutions to engage with Aboriginal communities and to support remote community collections, which have a direct impact on keeping culture strong.

AH: There is an acute arrogance embedded deep in the privilege of non-Indigenous Australia. Sometimes it is loud and other times very soft, almost inaudible, but it commonly says: I can paint this. I can photograph this. I can speak of this. And I can live here. I want to ask in return, to myself as much as anyone else: Can you really?

KB: I’ve been surprised by some responses from non-Aboriginal friends who have questioned why I consult and seek permission to make and exhibit the stone tool series in Perth. A common response has been, ‘why complicate things, just do it’. For me, this raises questions about how cultural materials are moved through galleries and museums in Western Australia.

In my hometown of Wellington in New Zealand our national museum, Te Papa, has a bi-cultural model for the handling and storage of taonga, objects of social or cultural value. Te Papa’s Mana Taonga policy ensures the physical, spiritual, cultural wellbeing of taonga and ensures engagement by the source community. It is an inclusive model that is not only done for Maori taonga, but everything the museum collects. A karakia (prayer) is said before and during the installation of any new exhibition to ensure the safety of the objects and those working in the space.

Worrorra artist Leah Umbagai taught me that Wandjina Unggud people have a responsibility to protect their country and to protect the welfare of visitors to their country. Visitors put themselves at great risk by entering sites they know nothing about and can unknowingly jeopardise the stability of ancient rock art, stone arrangements, deposits of bones and artefacts. In saying that, there needs to be opportunities for people to learn about these very real risks.

But perhaps you and I are in a privileged position. We have colleagues, friends, and for you family, who teach us. For many non-Aboriginal people born in Australia there is this idea that the island of Australia is one country, as opposed to the many countries we have learnt about.

AH: Maybe the abode of non-Indigenous Australia is better understood as one of migration and the permanent status of an uninvited guest. Not necessarily always unwelcome, but certainly uninvited. I would like to reckon with that. I would like Australia to reckon with that. Uninvited guests tread lightly, and they also have to listen carefully. As individuals, families, and as a community the size of a nation we need to learn to do these things.

It seems to me you have found your way through relationships that seep into your personal and professional life with the gentle permanence of stained ochre ¬— as you and Tim Winton so eloquently described.

KB: Hearing Aboriginal people say that ‘whitefellas have no culture’ has deeply challenged me. It inspired a journey of self-discovery into my identity as a Pakeha from Aotearoa, New Zealand, with ancestral links to Scotland and England. The diasporic movement of my family to New Zealand from the mid 1800s onwards, several world wars and the break away from shared intergenerational homesteads, has certainly played a role in the loss of my family’s own knowledge and traditions.

My view of Australia comes from an international perspective, and perhaps this makes me more open to Aboriginal ideas and culture, which I see as being the heart of this nation. This journey of learning from Aboriginal Australia has only made me more aware, curious and critical of my own culture and connection to land.

AH: I’ve heard senior Gija artists say that ‘white fellas have no culture’. Most often it comes from the frustration of always being ‘looked at’ and studied by non-Indigenous researchers, or curators, or collectors, who fly in and then fly out. They ask their questions and then go. And the conversations are so very rarely mutually beneficial. But I don’t agree with it. ‘Whitefella’ culture becomes invisible because it is so very dominant. And this is its deep danger.

Similarly I understand your intention, by saying Aboriginal ideas and culture are the heart of this nation. But I don’t feel comfortable with it. Australia needs to earn the right to have Aboriginal culture at its heart, it needs to learn to ask Aboriginal Australia if it wants to be at its heart. Unfortunately, we’re not there yet. There is still so much reckoning to do.

Katie Breckon is an artist, educator and remote community arts worker based in the West Kimberley. Originally from Wellington, New Zealand, she is a multi-disciplined artist often exhibiting under her surname, Breckon. Find her at www.breckon.co.

Alana Hunt is an artist, writer and cultural producer who lives on Miriwoong country in the remote north-west of Australia.