Artists: eleven Collective - Abdul Abdullah, Abdul-Rahman Abdullah, Hoda Afshar, Safdar Ahmed, Khadim Ali, Eugenia Flynn, Zeina Iaali, Khaled Sabsabi, Abdullah M.I. Syed, Shireen Taweel

Curators: Abdul-Rahman Abdullah and Nur Shkembi

Opening a conversation across complex and sometimes divergent temporalities, Waqt al-tagheer is a political, personal and often poetic exhibition. With new work from eleven, a collective of contemporary Australian Muslim artists, the exhibition provides a much-needed alternative reading of ‘what is Australian art today?’, against the broader and more sweeping statements made by the Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art (showing concurrently as part of the Adelaide Festival).

Moving towards greater intersectionality within contemporary Australian art, there is a timelessness in this emerging collection of voices. Rather than an exhibition of “Islamic Art”, eleven makes clear that this is a group of independent, autonomous, Muslim artists. Curators Nur Shkembi and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah have formed multiple threads which tie the exhibition together - deep contemplation that moves beyond a linear understanding of time & history; political agency that acts to undermine and expose the system under which we live; ruminations of the complexity and anxiety of living in a post 9/11, post Cronulla world; and reflections on how minorities can and do occupy space in a cosmopolitan and globalised world.

Khaled Sabsabi’s The Speed of Light (2016) reveals the complexity that can be found in a seemingly unexceptional view of the sky from a studio in Sydney. The 11 video screens form a horizonless cosmos within which time and light become uncertain and unfixed. The soundscape is rhythmic, almost stuttering; at the centre of the work is a sense of stillness, despite the fact that this work is about the act of speeding up. Sabsabi’s aim is to reconceive light beyond its physical, energetic properties and expose its pure & divine qualities. He arrives at this by accelerating 218 hours of video surveillance into a one second image, his version of the speed of light. Sabsabi’s treatment of light is religious as much as it is technological, referring to the Sufi Muslim belief of true and divine light, or Nur. Though the divine qualities of the work are uncertain, its interrogation of linear time is emphatically poetic.

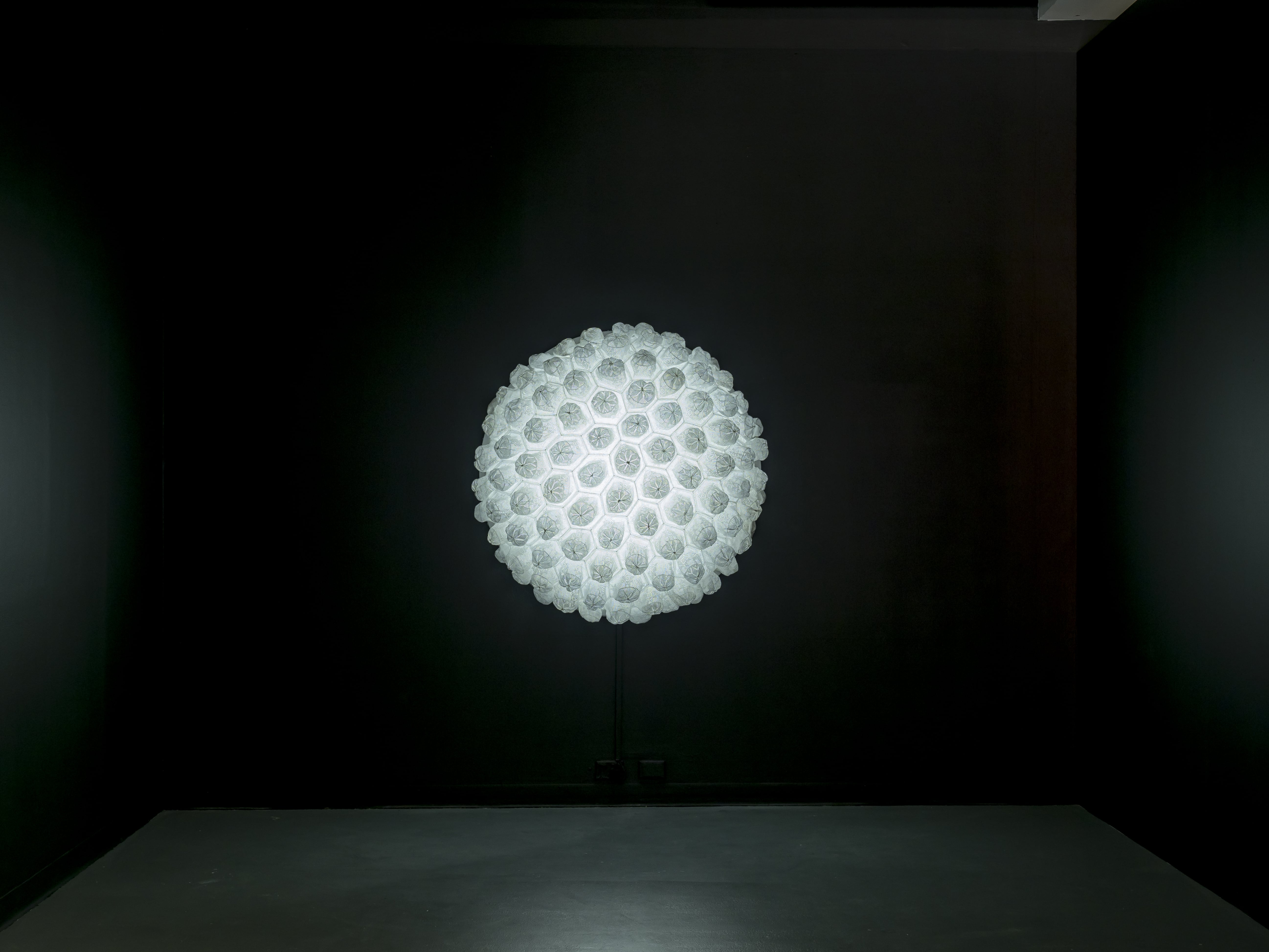

Light and luminescence feature elsewhere in the exhibition. Shireen Taweel’s musallah (2017) speaks to the history of Muslim faith in Australia, responding to the first mosque built in 1880 in Broken Hill, NSW. The hand pierced copper loop disperses and reflects light onto the gallery floor, creating a space that is sacred and intimate. Its elegance is paralleled by Abdullah M. I. Syed’s Aura II (2013) which likewise adopts traditional religious patterns, in the form of white prayer caps that he has used to form a sculptural glowing orb. Syed’s practice marries issues of cultural identity with poetic materiality, uncovering pervasive undercurrents of spirituality within a globalised and increasingly secularised world. His work using US$1 bills is transgressive; Untitled Objects (Devine Economy series) (2018) sees him working with Adelaide artist Carly Snoswell and members of the Handspinners and Weavers Guild of South Australia to produce a series of objects that reflect on Islamic iconography while highlighting the text ‘In God we trust’.

In a similar vein, Khadim Ali’ s two works reference both Western and Eastern art history, incorporating gold leaf as a motif to bring attention to the trauma of displacement, alongside Islamaphobia and Australia’s pervasive anti-refugee policy. The golden gum leaves glimmer with hope for a new life, but give way to an undercurrent of institutionalised racism and ‘othering’.

Waqt al-tagheer explores the Muslim Australian experience of being simultaneously silenced and also negatively highlighted in mainstream media. This is especially true for work by Hoda Afshar, Safdar Ahmed and Abdul Abdullah, who question the fabrication of Australian national identity, within which white normativity is a story backed by political conservatives. Abdul Abdullah’s lush photographic portraits illustrate the dehuminising gaze of racial prejudice. A recurring image within his work, the mask acts to subvert and obscure the identity of his subject. In the Wedding Series (2017), the bride and groom don balaclavas while uncomfortably and disinterestedly staring out of frame. Abdullah questions their subjects’ sense of belonging in a world that has them pegged as ‘future terrorists’. Likewise, his self portrait Journey to the West (2017) uses an ape mask to disfigure his appearance, becoming something monstrous. This work holds many parallels with Saftar Ahmed’s virtual reality work The Subjective Xenophobe (2018), which immerses the viewer in a dark, dystopian world. Using VR is an uncomfortable & disconcerting experience for the viewer at the best of times; Ahmed heightens the claustrophobia created by the apparatus by placing it in a public gallery context.

In her Under Western Eyes series (2013-2014) Hoda Afshar interrogates the icon of the veiled Muslim woman from the migrant perspective of double consciousness, presenting herself through the dominant colonial gaze. Ashfar takes on recognisable Western art devices to show how images have been made predictable and digestible for Western audiences. She literally puts a puppy on it, exposing the expectation for women to present as pacified rather than nuanced individuals. Zeina Iaali too questions the placation of women in her series Sweetly Moulded (2012), attempting to refocus attention on individuals to reveal their complexity. Eugenia Flynn’s text-based installation With my sister (2018) offers a similiar nuance, quietly but powerfully disclosing a deeply personal moment. Flynn’s poem extends backwards in time to a defining moment in global history; her vulnerability in this moment shows her agency. These works critique and decentralise the dominant Western, colonial framework by recentring on individual (Muslim) voices.

Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s personal history is the impetus for his work 500 Books (2018), and the curatorial starting point for thinking about the poetics and politics of personal identity within this exhibition. The beauty and skill of his hand-carved objects stand in for the hundreds of years of knowledge contained in the books that he represents. At first glance, the significance of the work is easily dismissed. But closer inspection reveals the depth of craftsmanship and devotion to practice.

Shkembi and Abdullah have curated works that reflect the multifaceted, maybe even multidimensional, aspects of time, with artists looking at the intersection of personal identity and broader histories. The exhibition provides diversity without tokenism, and is underpinned by thoughtful and critical texts in a new publication produced for the exhibition. For eleven, this exhibition is a significant presentation, creating alternative discourses for a national audience.

Adelè Sliuzas is an Adelaide based arts writer and curator. She is currently studying postgraduate Art History at Adelaide University and has a BFA from the University of South Australia. Her writing has been published in Artlink, Fine Print Magazine, Art + and Runway.