The coalition emerges out of your recognition that it’s fucked up for you, in the same way that we’ve already recognised that it’s fucked up for us.

—Fred Moten

Under a Burning White Sky

As my experience of social life has become less and less about seeking or gaining approval from outside forces, a burden has lifted, allowing me to find my way to the always already collective formation that is Black life itself, which links Afro-diasporic and First Nations people. Those who find themselves here revel in what so often remains hidden, namely Black lives and histories flourishing in flagrant disregard of whiteness.

Art is one location of this flourishing. It is a portal for our imagination, allowing collective social expression even while we remain oppressed politically and economically. We all need something to soothe us. We all need a private freedom outside the tunnel vision that invisibilises and suppresses us, a place where we can acknowledge the marks and scars, the heartache, racial profiling, lurid projections, nervous breakdowns — all the pain with no name that many of us and our communities bear. And if we stop and reflect on the denied truths that haunt the world we live in — from invasion to enslavement to colonialism to assimilation to police brutality to the legacies of quotidian racism — it is little wonder that our art often speaks to an impossible daring: remembering the unknown, hearing the unspoken, seeing the invisible, communicating with unheard voices.

We have a story to tell that cannot be told yet must be told.1 This storytelling is often exhausting work. It is also a coping mechanism, a way of bringing a new, less disturbed rhythm onto planet Earth. We know everything is not going to be alright. Unless there is a destruction of what we know, it’s not going to be alright. So we escape the sad, rabid miasma of struggle and futile outrage by slanting our lived reality to create room for art. We create space for fantasies of ourselves, spectral apparitions between the real and the imagined, space for a way of being together in our incompleteness.

Fade to Black

Karrabing Film Collective’s The Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland (2019) is one of those works of art that can make us believe, that can take us to that space somewhere else. It’s an ode to time travel — hallucinatory and frayed at the edges, a fragmented and psychedelic quest. The film opens with disorienting noises in a hospital. The camera angles are slanted.

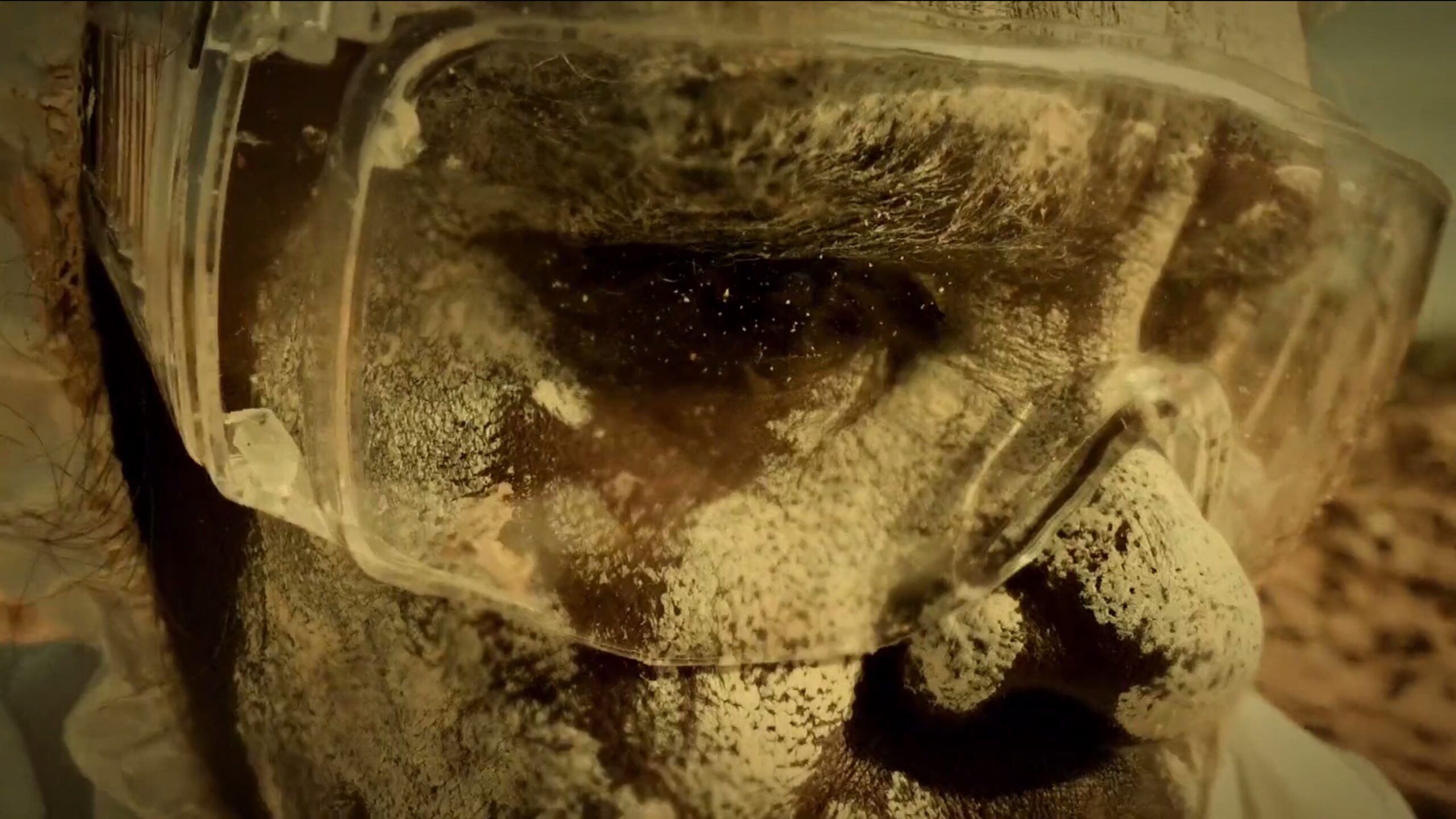

A Black body is on a hospital bed, hooked up to a machine with tubes. The camera pans and jumps: a poetics of the blur. ‘What you doing?’ the body on the bed asks. A young Black man responds: ‘They say it’s not working. They going to take me back.’ Bodies in hazmat suits hint at a time out of joint. A voice off-camera confirms: ‘The land is poisoning us not them.’

Karrabing throw us into a world made sick by capitalism, a speculative future where only non-white people can survive outdoors. We find out the young Black man we just met is named Aiden, and that he was stolen when young as part of a medical experiment to save the white race. He is our hero, our guide. We follow him as he returns to the world of his family, struggling to understand their ways. We watch his journey to find the answers he seeks and we ride a wave of histories and dreams. We listen to a First Nations creole and are rocked by shifts in time. And like Aiden, but from a safe distance, we too become acquainted with vitality: the mermaids, a sugarbag bee, a blowfly, the pelican Dreaming and a cockatoo.

The Karrabing Film Collective runs counter to the norm, modern revellers forged together in the making of art but birthed at the altar of revolt. They are a collective of friends and family whose lives interconnect along the coastal waters west of Darwin, and across Anson Bay at the mouth the of the Daly River, fanning outward into a global network of academics, artists and filmmakers who they collaborate with to articulate the longstanding colonial violence that impacts Black lives. They refuse the burden of the structures we inhabit and that inhabit us — settler colonialism, racialisation, organised abandonment — even as they foreground how these burdens shape their lives. They are a motley crew who, like the tides, come together and move apart as different aspects of their lives converge and dissipate. A mix of artistic experimentation and political radicalism, their work challenges the narratives imposed on marginalised communities by those in power. They understand how film can be used to analyse contemporary Australian political culture by opening a space beyond the binaries of the fictional and the documentary, the past and the present. They offer pointed, witty meditations on the impact of environmental devastation, land restriction and economic exploitation on racialised communities.

An inventive filmic language underscores The Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland. The use of hand-held cameras, saturated lighting and the superimposition of images produces a sense of disorientation in the viewer. On the level of narrative, the unravelling of several different strands of inquiry — from metaphysical questions about the nature of reality, to the critical exposition of the destructive force of capital on the environment — forces us to contend with several competing melodic lines at the same. The effect is akin to listening to Thelonious Monk’s unusual harmonies and dissonant chord voicings that somehow cohere in an arresting kind of jagged resonance. The Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland is calling on us to see, hear and otherwise sense our world differently.

In the Swell of Things

The Karrabing Film Collective’s willingness to probe the space of organised abandonment is no surprise when you dig into their background. You end up realising that theirs is a hard-earned wisdom gained from living in the Black everyday.

The origins of the Karrabing Film Collective can be traced to 15 March 2007, in Belyuen, when members of the collective were caught in the grip of a riot. They watched as their cars and houses were torched and their dogs beaten to death. Intending to live closer to their ancestral lands with the help of government support, they left town for Bulgul. They set up a tent settlement. They waited for the promised new housing, schools and jobs. And as they waited, Federal Government policy took a startling turn. On 21 June 2007, in the wake of a confected moral panic over alleged endemic child neglect and sexual abuse in Indigenous communities, the Australian parliament passed the Northern Territory National Emergency Response Act (2007). Also known as ‘The Intervention’, this piece of legislation claimed special exemption from the Racial Discrimination Act (1975). The members of the collective were now told that the promised government support was no longer available. Instead, they received alcohol restrictions, child welfare inspections and a marked increase in policing. It was out of this particular paternalistic state of exception that the Karrabing Film Collective became a thing.

It is important to stress this state of exception because First Nations lives in Australia are subject to a distinct form of racialisation in the Black everyday. State-sanctioned violence doesn’t affect us all the same way. We need look no further than ‘The Intervention’ for hard evidence. The perverse logic of assimilation tore through metaphysical and material relations to land, culture and spirit in an attempt to force a segment of the Australian population to participate in the dominant political and economic framework.

The Mermaids, or Aiden in Wonderland responds to the seething presence, the ghosts of this wound. The spotlight is cultural memory, place and ancestry. The film offers a fresh approach to Black testimony, at once direct and alluring. We are pulled into a structure of feeling that gives us room to remember the unknown, hear the unspoken, see the invisible. This is a film that leaves behind vexing questions — thoughts lingering on the threshold of consciousness. Watching it we get the feeling that the Karrabing Film Collective wanted to share a secret but instead they ended up making a work of art and waited for us to experience the secret for ourselves.

What’s Art Got to Do With It?

Art is where we can open space for an elsewhere within the current configurations of power so that we can be the recipients of endless oppressive strategies and survive it with our souls intact. We can express ourselves on our own terms. We can revel in being our truest selves. But part of the Black experience in art is the lurking white desire for a palatable, consumable difference. We’re told again and again that our work must be comprehensible and intelligible for the very forces that are arrayed against us everywhere that we are.

Let us voice the denied truths that haunt our world and let that voicing spill over into life, where we find an impossibly healed Blackness, an impossible wholesomeness, waiting for us on the other side of our fragmented, fevered works of art, which we love and need and gorge on with delight.