Where We Stand (2018) choreographed by Isabella Whāwhai Mason (Ngāti Tukorehe, Te Ātiawa), performed by Ngioka Bunda-Heath (Wakka Wakka, Ngugi, Biripi), Pauline Vetuna (Tolai/Gunantuna), Hannah Troth (Aeta), Janina Asiedu (Akan Akyen), Fallon Te Paa (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Whātua, Te Ātihaunui-a-Papārangi, Manihiki), Kathleen Campone (Italian, Irish, English, Scottish), Jazmyn Carter (English, Irish, Scottish, Yugoslavian), Anika De Ruyter (Scottish, Irish, English, Dutch), Ebony Howald (Swiss, English) at Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne

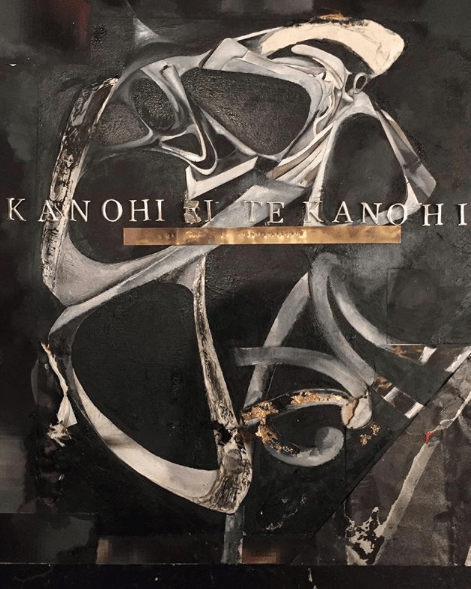

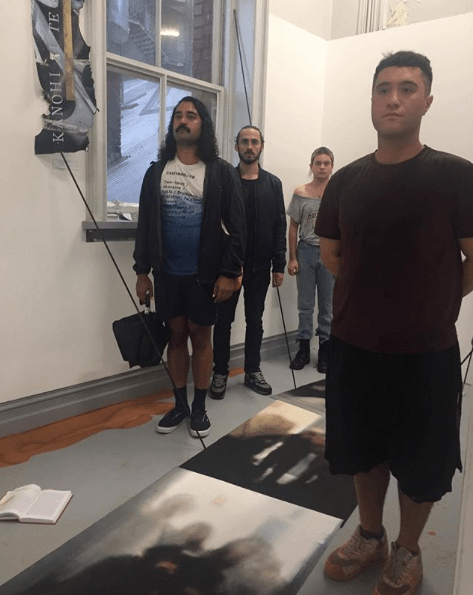

Kanohi ki te kanohi (2017) by Tyson Campbell (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Maniapoto) with Adam Ridgeway (Worimi), Sean Miles (Ngāti Raukawa), Léuli Eshraghi (Āpia, Leulumoega, Siʻumu, Salelologa), Sian Petricevich (Ngāpuhi), Leah Avene (Nanumaga) at School of Art, RMIT University

During 2015, the Institute of Modern Art in Yuggara and Turrbal Country asked makers, organisers and thinkers, ‘What can art institutions do?’. Later, the responses were assembled together in a symposium and publication. In rebutting settler art historian Ian McLean’s proposal that there is a black museology in place, prominent Kuku Yalandji, Waanji, Yidindji and Gugu Yimithirr artist Vernon Ah Kee instead affirms that mainstream art/history, whilst considering Aboriginal practices, cannot be mistaken for actual black self-determination. When Eurocentric institutions of settler coloniality are not bound to repatriate power or presence to First Nations, they cannot cancel their structural imbalances and change beyond lip service or woke respectability:

“I believe we are yet to see an Aboriginal curator. Every curator is beholden to their institutional authority, which is beholden to its funding sources. Curators and institutions are obliged to follow a curatorial premise that serves the national narrative. While it may not yet be possible to have an Aboriginal curator, it is possible to have a strictly Aboriginal curatorial premise. An artist collective can present an oppositional position to the national narrative. As Aboriginal people, we come from an oppositional context to the white Australian one, politically, historically, and socio-economically.”1

In considering how we might understand the work of Indigenous artists from other territories devastated by settler colonial, slavery, military and resource extractive forms who live and work in these First Nations lands, we can remember that institutions mean different things to us. As diasporic Indigenous peoples living in Kulin Nation territory, the kinship and solidarity-based actions in support of local sovereignty that we must develop and maintain as guests here are pivotal. Ngāi Tūhoe curator Ngahiraka Mason reminded me a few years before she curated last year’s brilliant Honolulu Biennial that the relationships we maintain are our institutions as Indigenous peoples, that for all the bricks and mortar that settlers build, our institutions do not require buildings for we carry them.

This emphasis on kinships between all living beings including lands, waters, skies, gods and ancestors is an enduring organising principle of all Indigenous existences. In settler performance and visual culture, institutional critique remains an ongoing concern but with different imperatives to our own. Two works by Māori artists living along Birrarung-ga around the great bay Narrm that I experienced recently offer bold propositions and yet continue to suffer from the unbearable whiteness of arts institutions – in what James Baldwin described as ‘ever racist institutions’. Whilst recent appointments to major exhibitions and institutions are promising and help us to continue world-making, these are still exceptions to the focus on demographic-majority Caucasian diasporic audiences first, and Indigenous audiences from various regions last.

Where We Stand (2018) by Ngāti Tukorehe and Te Ātiawa choreographer Isabella Whāwhai Mason received a number of wannabe shock jock reports in conservative papers on its apparent racialised segregation of audiences. The irony here is that all galleries for the display, and stages for the performance, of cultural practice in Birrarung-ga are already always centred on a whiteness that cancels and disallows us others – Indigenous, Black, Brown, Yellow, Mixed, non-European communities.

Staged in the VCA performing arts building, the first wave of invitational relationship sees Ngioka Bunda-Heath lead audience members identifying as Aboriginal and/or Zenadh-Kes/Torres Strait Islander into the theatre. What occurred there is not for me. A few minutes later, Fallon Te Paa leads audience members identifying as Indigenous, Black, Brown, People of Colour into the theatre. There is a pōwhiri call and response from both parties before we are beckoned in to sit on pandanus mats that I recognise as being from the central islands of the Great Ocean, Tonga, Viti, and my home, the Sāmoan archipelago. We hear deeply emotional and lyrical testimonies about ancestral Indigenous connections in territories today named Australia, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Ghana, New Zealand and elsewhere. This is for us, as Solange reminds, a specific Indigenous technology often called yarning, kōrero, talanoa, stori.

What occurs outside in the foyer for all the Caucasian people is not known to me. The performative storytelling on the mats in the centre of the stage abruptly stops. In tense silence, the performers stoically stare down the audience, joined by choreographer Bella, who repeat that they are refusing to go on because the dynamic between Indigenous/Peoples of Colour and white people has turned from our favour, requesting us to all reflect on this. More white people enter the space and awkwardly take seats near us and in the stalls distant from the shared pandanus mats. I want to call this a sovereign act, I want to call this a display of embodied Indigenous refusal, but the structures don’t change afterwards. I wait for an intervention in the next performance on the bill, typical Caucasian dance aesthetic, but it never comes. The Indigenous/Black/Brown/Yellow incursion is over, we are back to white normality on the stage. I wait for Pauline Vetuna to return and loudly proclaim in English what Kuanua language sounds are, what Tolai/Gunantuna world-making feels like in communing with Ancestors who visit often, who grieve and search and haunt the living. She does not appear.

We had initially entered following Ngioka’s acknowledgement, itself guided by the Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development – the only such philanthropically-funded centre in any Australian visual and performing arts educational institution. I knew a number of fellow community members in the audience from the Great Ocean we hail from. We implicitly agree that we would not be in the space had we not come for this work. The unbearable whiteness of stages and walls in Australian theatres and galleries leaves me weak, exhausted and tired of hoping for a cluster-hire of messianic artistic directors with vision and humility.

Kanohi ki te kanohi (2017) by Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Maniapoto artist Tyson Campbell received significant negative reactions on the part of staff and property services from RMIT, where the work took place. The performative work saw Tyson lead five Indigenous artists and musicians – myself included – living and working in Birrarung-ga in a line, in the rain, trailing mud from regional First Nations’ riverbeds (with permission) from the colonial statue on Lonsdale St, through the buildings hosting the RMIT School of Art’s graduation exhibition and onto the top floor segregated room that Tyson had been assigned. Following repeated propositional works engaging kinship with land, water, sky through Indigenous epistemology, this final performative installation literally marked the colonial buildings with clay as an affirmation of Indigenous existence. What is complex here is that we are not from here, we are adjacent relatives to these experiences and yet they mirror our own. Kanohi ki te kanohi i te pai whakarangaromanga is a phrase in reo Māori that signals the coming together of multiple elements, participants, face to face. The Eurocentric visual aesthetic at home in the larger Caucasian diaspora does not make or consider making space for Indigenous conceptions of time, space, kinship – where making, organising, critically considering and future-making are together in how and why we make. What I mean is that the lack of critical mass, non-tokenised presence and power for First Nations first – and diasporic Indigenous and Peoples of Colour later – in settler colonial institutions stifles any real engagement with our work, our bodies, our urgencies.

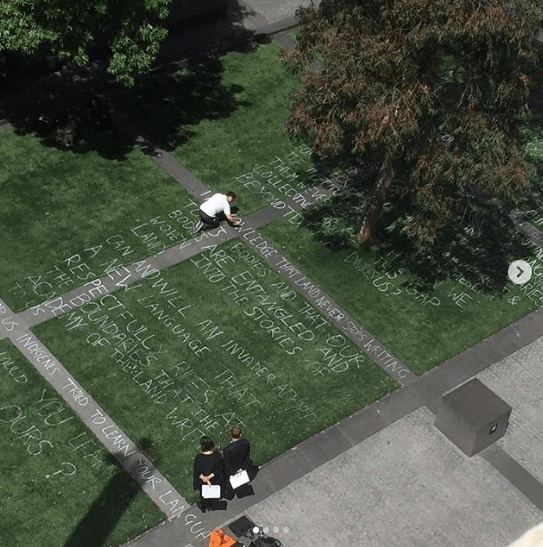

Our own bricks-and-mortar Indigenous art institution, Blak Dot Gallery, was rejected as a site for Tyson’s assessment work despite reasonable requests to RMIT School of Art staff. Upsetting the status quo in this eventuality would have meant that the Māori aesthetic and ceremonial-political practices that Tyson draws on, would be contextual to south-eastern First Nation aesthetic and ceremonial-political practices. We would have been able to control the site/sight, the budgets/programming and audiences/publics. Whilst we garnered much attention in the graduation show crowds as we walked through the levels and spaces with the trailing mud, Tyson repeated the text he had been targeted for by property services earlier in the semester (chalk lines on AstroTurf apparently merit a $2,000 cleaning fee even though the rain would clear it):

As invaders, uninvited guests in unceded First Nations territory, how can we move beyond text to undermine and rearrange the classic. To generate a new language, a hybrid of new materialism, that speaks of story, body and country? For if ‘the sign never appears the same twice’ (Saussure), our memory of an event, idea or happening is overwritten when we revisit it. Text in this case, is always writing and rewriting itself, shifting and rearranging its value, creating connections and disconnections, that project and possess understandings beyond binaries, in time and space.

Forgotten communities never forget, and the institutions that don’t represent them never remember. How can we collectively bridge this gap beyond text that divides us? I acknowledge that land never stops writing to its bodies, and that our bodies are entangled and woven into the stories of land. Can and will an invader adopt a new language, that respectfully rides at the boundaries that the academy of the land writes to us. Us indigenes tried to learn your language, would you learn ours? With love, from a noble savage – inspired by a white woman.

When we reach the final cordoned-off room where Tyson’s photographs, sculptures and muddy surfaces are assembled, Tyson raises his voice higher, louder, and after a long moment, slams the door shut. We, the assistants in this performance, burst into tears, shocked at the emotional labour we moved through, the healing we moved through, then and on countless other occasions, in making our belonging known and heard.

Affirming the place of Indigenous creative practices in the racist institutions of visuality and performance, both Bella and Tyson’s works cannot be framed in relation to key Māori practices or hallmark works within Aotearoa’s production and exhibition histories, as they are not known well enough here despite generations of diaspora. It is instead necessary to locate these works in the language of Indigenous future-making, of collective sensual and ritual action, in deference to First Nations aesthetic and ceremonial-political practices, even more underrepresented and misunderstood in these institutions. In antagonising the settler colonial status quo and staking claims to the centrality of local and global Indigenous practices, these works destroy the consumptive, extractive, comfortable gaze that has powered Euro-American societies through pillaging and destruction. Racial hierarchy is part of an unenlightened civilisational hierarchy that those in Europe – who were divorced from their own responsibilities to lands, waters, gods and ancestors – forgot and buried. Our works are for us, and whether the kinship-based access to these works upsets a comfortable settler diaspora is irrelevant. We are yet learning in the commutes in every direction in time and space.

Léuli Eshrāghi [Sāmoa, Irānzamin, Guandong; pronouns ia, ū or any others] is an artist, 1/5 curators on The Commute at the IMA, and Monash University PhD candidate, grateful to live on Kulin Nation territory. Ia work centres on ceremonial-political practices, language renewal and Indigenous futures throughout the Great Ocean. Ia exhibits and publishes regularly, and serves on the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective (Canada) board and un Magazine editorial committee.