Curator: Maria Morata

Artists: Suzanne Treister, Pinar Yoldas, Lu Yang, Marco Donnarumma, Renaud Marchand, Yvonne Roeb, Alan Warburton

For those unfamiliar with the term ‘posthuman’, Maria Morata’s curatorial project Zoextropy. The Posthuman Beauty could suggest a world filled with monstrous dystopic creations. Perhaps one might envision a spectacle, something along the lines of enthusiastic technophilia, or visions of a sinister yet beautiful dystopia — one might imagine encountering aesthetically fascinating cyborgs and other half-human creatures that threaten our assumed humanity. While these binary clichés of either utopian of dystopian futures sometimes appear to be associated with concepts of the posthuman, Morata’s exhibition takes a different tangent, blurring and questioning the boundaries between human and non-human through a selection of works that reimagine sci-fi aesthetics and emphasise speculative narratives.

Upon entering the gallery space, one is transported into a fictional universe, enveloped by the blackened walls of the gallery and enthralled by the mysterious atmosphere that emanates from the artworks. Like being inside a pseudo-scientific laboratory, the exhibition is an assemblage of the hybrid and the speculative: botanical drawings presented on tables, Perspex cylinders containing unrecognisable plants, a small sculpture made from dust, several videos, as well as a collection of totem-like artefacts are some of the artworks the viewer encounters.

Taken as a whole, the exhibition decentres the human body within a system of non-human elements, such as plant ecologies, economic structures, artificial materials and technological systems. By approaching the concept of the posthuman from this place of expanded hybridity, Morata disintegrates the idea of the human as the main principle of organisation and thus allows for posthuman narratives to emerge that are neither strictly utopian nor dystopian.1

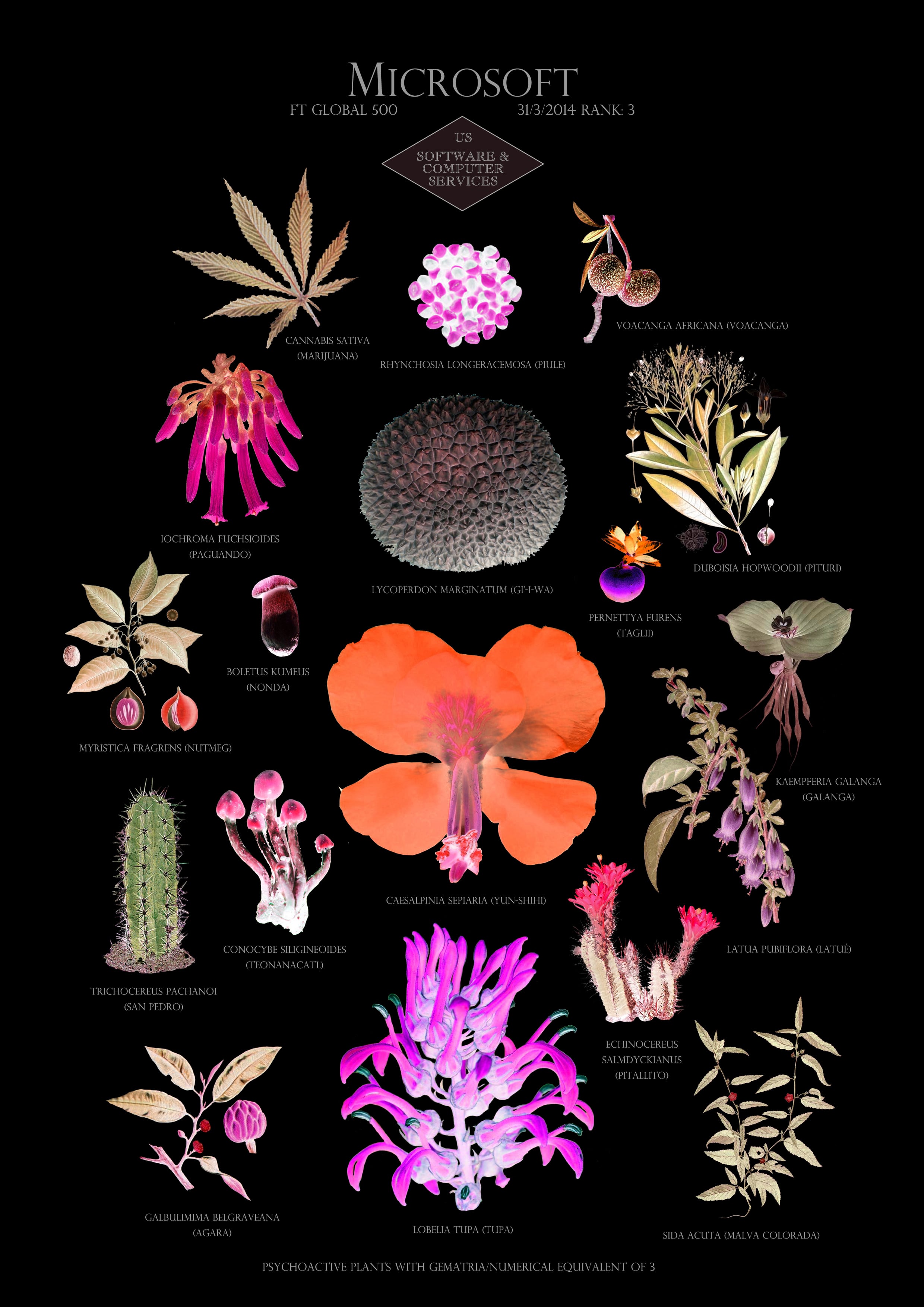

A sense of systematic hybridity is especially evident in Suzanne Treister’s HFT The Gardener (2014-15). The video narrates the story of Hillel Fischer Traumberg, an algorithmic trader who becomes obsessed with botanical science. Treister’s fictional protagonist establishes ambiguous relationships between chemical compositions of certain hallucinogenic plants, their healing qualities and the colourful drawings of outsider artists and botanical illustrators. Hillel then decodes a selection of plant names into numerical values by employing various language systems. Once decoded, the plants’ botanical names reveal their secret relationship to the world of finance, via their association with trading algorithms of influential, global companies. In doing so, Treister’s speculative video reimagines the relationships between systems of organisation, capitalism and aesthetics. Plants become embedded in systems of commerce and monetary value, and in linguistic, numerical and visual taxonomies. Botanical knowledge, the economy, practices, patterns, language and art thus intersect. Within this speculative system, the position of the human is decentred and ambiguous. Taxonomies might have been humanly constructed at first, but they have since taken on a secret life of their own, generating a hybrid structure of interconnected and enigmatic complexity, which The Gardener slowly reveals .

Lu Yang’s video, Delusional Mandala (2015), also interrogates a sense of expanded hybridity, this time between digital imaging technologies and the human subject. Yang’s CGI generated video projection examines the virtual representation of the body and the self in the form of a non-binary digital avatar, playfully mixing medical imaging technologies with questions of consciousness, the human brain, medical science, spirituality and subjectivity. The animated avatar of the artist is produced by 3D scanning technology, its bodily structure mapped by medical imaging tools as a means to create ‘a personal mandala’. In that manner, Yang constructs her avatar as ‘a metaphysical universe’ of herself.2 Referencing and mixing neuroscience with meditation and non-specific religious practices, the avatar’s nervous system gets prodded and manipulated by fictional medical procedures that can alter states of human consciousness. The work interrogates concepts of the physical self and that which we consider makes us who we are: namely, human consciousness. Yang’s video also touches on ideas concerning the self and consciousness after death, through means of the digital avatar. Via its open-ended nature, the work does not suggest futures so much as pose questions concerning the body, subjectivity, ethics and the manifestation of the digital self.

Other works in the exhibition explore hybridity through a speculative merging of, and interaction between, artificial and organic materials and matter.

Marco Donnarumma’s installation Calyx (2019) blurs the boundaries between violence and play and between artist and machine. The installation comprises multiple layers of skin-like membranes suspended from the gallery ceiling. Upon a closer look, the artificial skins reveal intricate patterns of cuts, produced in collaboration with an A.I. controlled robotic limb; a video next to the work shows the cutting process. The work speaks to the potential manufacture of bodily materials, and to the potentially violent processes therein. At the same time, it reveals the emergence of collaborative play between human and intelligent machines. Alan Warburton’s Dust Bunny (2015), on the other hand, makes visible the inherent coexistence between organic matter and computer technology. His small, bunny-shaped sculpture was made from four years’ worth of accumulated dust, collected from within the casings of computer rendering farms.

Several works in the exhibition also focus on speculative new organisms, engaging with hybridity though concepts of evolution, such as can be seen in Pinar Yoldas’ installation of plastic underwater plants, An Ecosystem of Excess (2014) and Yvonne Roeb’s collection of sculptures which mix familiar animal skeletons with unrecognisable lifeforms.

Taken together, the works in this exhibition effectively transcend some of the clichés surrounding posthumanism, such as the belief that the concept of the posthuman might construct a dystopian, sinister future. Instead, the exhibition suggests a complexity of ideas and possibilities, without a fixed moral evaluation.

Overall, the exhibition explores possibilities of ‘what if’, positioning the human not at the centre but as part of complex systems, highlighting the visible and immeasurable connections between different elements. Morata’s curatorial choices reflect a deliberate exploration and extension of the at times dramatic aesthetics associated with science fiction and futuristic imaginaries. In contrast, the exhibition achieves a nuanced exploration of notions of aesthetic and theoretical hybridity, focusing on possibilities for ‘posthuman beauty’ established through the relationship between systems and substances that exist alongside the human body.

Corinna Berndt is a Narrm/Melbourne-based visual artist and current PhD candidate at The University of Melbourne, Faculty of Fine Arts and Music. Her current research focuses on the potential impact of historical techno-imaginaries that dominate Western culture.