Cache, Melbourne

Clara Joyce - Breathing and Chaos

6.4.24 - 7.4.24

I’d love you even more if you came with me. I was underway, underweight and emotionally charged entering the building. With bleached streaks and big pillows under your painting desk, I've followed you ever since you melted my legs, right in front of me in the lobby.

When I see Breathing and Chaos, I am preoccupied with soul-seeking. Heat rises within me. My reflections become sacred all of a sudden. A prairie oyster of a show, slapping me out of my blazed life. My gaze magnetises towards the blue circle to my left, Dew Shift, which pulsates out of the canvas. Dark angular shapes crowd a blue sphere that glows across the room. It produces its own eminence, a shy object in itself, yet it holds the answers, as pupils usually do.

Like a kindred illusion, your body heat was felt.

The painterly assumptions of this show evince Clara Joyce’s steps beyond last year, our Fine Arts Honours year, when we shared studios a few metres apart. The light always hit her work in a way that could never touch the other studios. There was a moment when Clara began to paint from home more often. In solace, she produced her best works, and as we now see in Breathing and Chaos, she has crafted a new age of painting fit for loosely circumventing the mind. I want to speak with the unknown force that sat next to me while I observed Clara in her home studio last week. “3pm has the best light,” she said, and indeed it was then that I reconciled with the force of light around and within her work.

Cache is a ripened space with fleeting shows that I hadn’t been able to catch so far. Previously a RMIT architect's personal archive and office, Cache’s identity remained sealed. And now, opened like a vault by Tommaso Nervegna-Reed, past dynamics of knowledge storage are rewritten to cast light onto new artists. The space’s transition to an art gallery seems to retain the essence of knowledge embodied by the previous enclave of architectural books. I said vault, but I really meant cage, for Cache’s structural integrity is owed to tall black metal cages along the walls that continue to the top of the room, creating a loft situation.

Almost mistaken for a metal railing is Vertical Annunciation, the only sculptural aspect of the show. Clara’s other sculptures have been more like instruments to see her paintings with, often distorted optical illusions such as looking glasses and clear warped bowls. Here she constructs a real instrument. The horn is a plentiful omen that can be traced throughout history as a motif depicted in religious or allegorical contexts. The trumpet’s association with the Archangel Gabriel, who is traditionally believed to have announced divine decrees, gave the name ‘Gabriel’s Horn’ to this shape. The object is 183cm tall (Clara’s exact height), and is mysteriously attached to the black cage platform above. The fibreglass and resin is dusted with a coating of graphite, mattifying what would typically be polished brass. Gabriel’s Horn is also known as The Painter’s Paradox, a mathematical equation based on the fact that the horned object has infinite surface area and finite volume—meaning the artist can calculate how much paint is needed to fill the horn, but will never have enough paint to coat the outside. Relics throughout time seem to emanate this concept; angel trumpet flowers, cornucopias, rhinoceros beetles, antelope horns, bugles and gas air horns. Moreover, in 1511 Albrecht Dürer depicted seven angels with skinny trumpets for The Apocalypse book and in William Blake’s illustrations for Robert Blair’s poetry book ‘The Grave’, The Skeleton Re-Animated (1805-1808) sees a long horn sucking/blowing the life in/out of a skeleton.

You’ve pulled me out of what I thought was a hole, but when I turned back for the last time, it wasn’t a hole but a brilliant void. This secret exchange of ours cannot go on any longer.

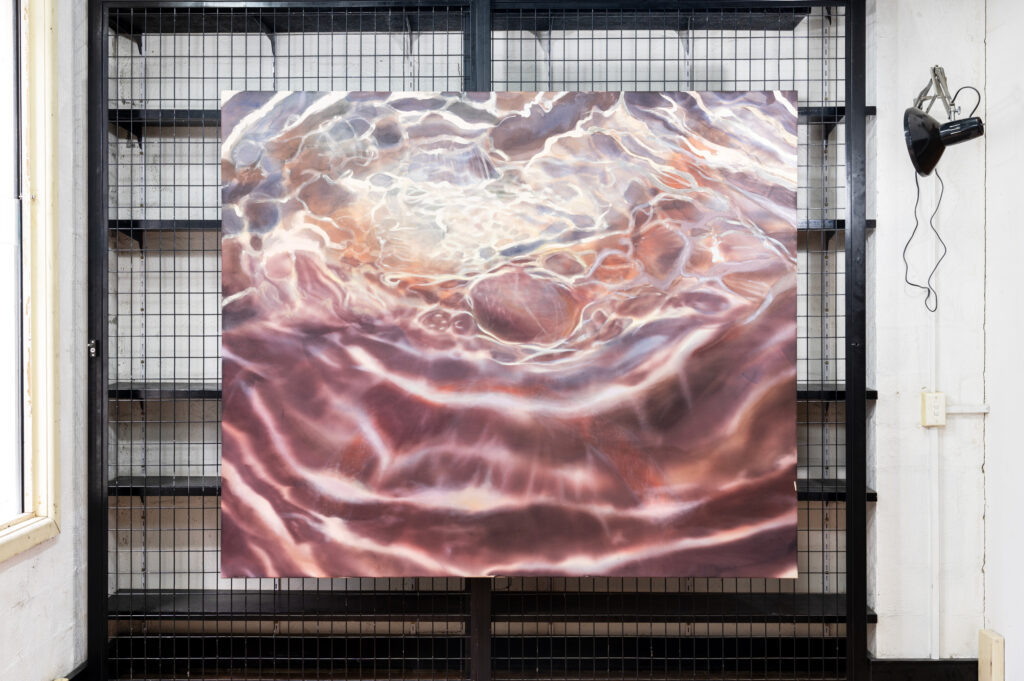

The show's title is also the name of its largest painting. On the right side of the room, it anchors everything with its soul that sticks out everywhere. I find comfort in this work amongst the sound-polluted city. Very few works make me feel that way, as a lot of Melbourne’s art is synchronised with the dregs left by the city's fast pace. The painting slowly swallows itself, rolling over, drinking, churning, eating the world as it moves along. It is beautifully mauve in all its shades. Clara lets the bottom of the painting rest smoothly and blurred while the foreground at the top reveals her heavy painter’s stroke. When I swim at the beach I swim far out, I lay on my back and inflate my lungs so I stay buoyant, then I breathe out and let my body sink while I stare up at the sky. I see rings of air bubbles leave my body the further down I go. Breathing and Chaos is a glimpse of the moment when I’ve sunk halfway down the ocean and I can't decide whether to stay down or come up.

I breathe the air the painting breathes along with the air Clara breathes. In unison we conclude our breaths. Clara taught me how to breathe with my stomach, in and out, navel-gazing. She says to listen to your gut and stick to a tempo determined by the body’s internal rhythm. In a way, with Cache’s re-definition of what wall space is, the canvases hoisted onto the cages allow them to breathe from the back as never before. Try witnessing a painting by only breathing with the back of your lungs or deep in the stomach; some somatic mind-gut practice. I’m yet again digesting an exhibition. This time I’m left feeling full.

Clara usually stains the canvas, and here she sits within the layers. When the paint stains bleed out, as seen in Diffusion Principles and Swan, they leave an ever-expanding stroke. Both works delve into khaki territory: professional colours, not distracting, prude yet sophisticated. While Diffusion Principles uses diluted paint to bleed outwards, Swan’s bleed drags down the canvas. In Swan, two darker red splotches resemble bruises, while on Diffusion Principles the central subject mimics crooked vertebrae. The paint around this shape seeps out eternally, preserved by dry air and light. When Clarice Lispector wrote Agua Viva, she spoke of these negotiations between the choice of eternity and the beginning and end to something, and with that the utmost fear of which both options bear.

Clara’s paintings are clairvoyant – they are to be gazed within not upon. You may ask them questions and they may respond. My friend once tweeted, “i fucking hate surprises, thats why I started drinking magic 8 ball liquid”. To use that allegory, drinking Clara’s paintings enlightens me with the secrets of tomorrow. I’m pressed to ask more questions, I’m pressed for time, I’m a pressure point altogether.

This transcript goes back and forth, until, well, we die.

The sun is too full as it shines onto my full-circled thoughts. The paintings turn from liquid to gas, and back again. Akin to von Bingen’s ‘Voice of the Living Light’, combating the lume isn’t in Clara’s best interest. In fact, she holds it close to her chest. As the pendulum swings from its motionless point amidst the Earth's ceaseless rotation below, I sense anew my place in this life again. At this perishable instant I regain consciousness. I grip the hand of the painting and we hold each other tightly. I unfold only now with Breathing and Chaos.

Fallen over, I’m beset with grace. I dare not over observe you.

It’s the autumn heat, blame it on the autumn heat. An autumn show truly.

Honestly, many things became clear the day I saw this exhibition, I noticed my hair again. I figured out the spin of the earth. With my body bound to the right corners, I spun along with the rest of the world.

Margarita Kontev is a writer and emerging curator.

Edited by Ella Howells. un Projects’ Editor-in-Residence Program is supported by the City of Yarra, Creative Victoria and City of Melbourne.