Nanette Orly and Sebastian Henry-Jones are two Sydney based curators who are doing things differently. Their curatorial practices are collaborative and artist-led, and for them inclusion and diversity are not simply boxes ticked but entrenched ways of working. Theirs is a subtle and destabilising activism that models a better, more dialogical way of curating across cultures. The three of us sat down in July, during their recent exhibition I will never run out of lies nor love at Bus Projects, Naarm/Melbourne, to discuss language and the language of silence, the premise upon which this exhibition is based.

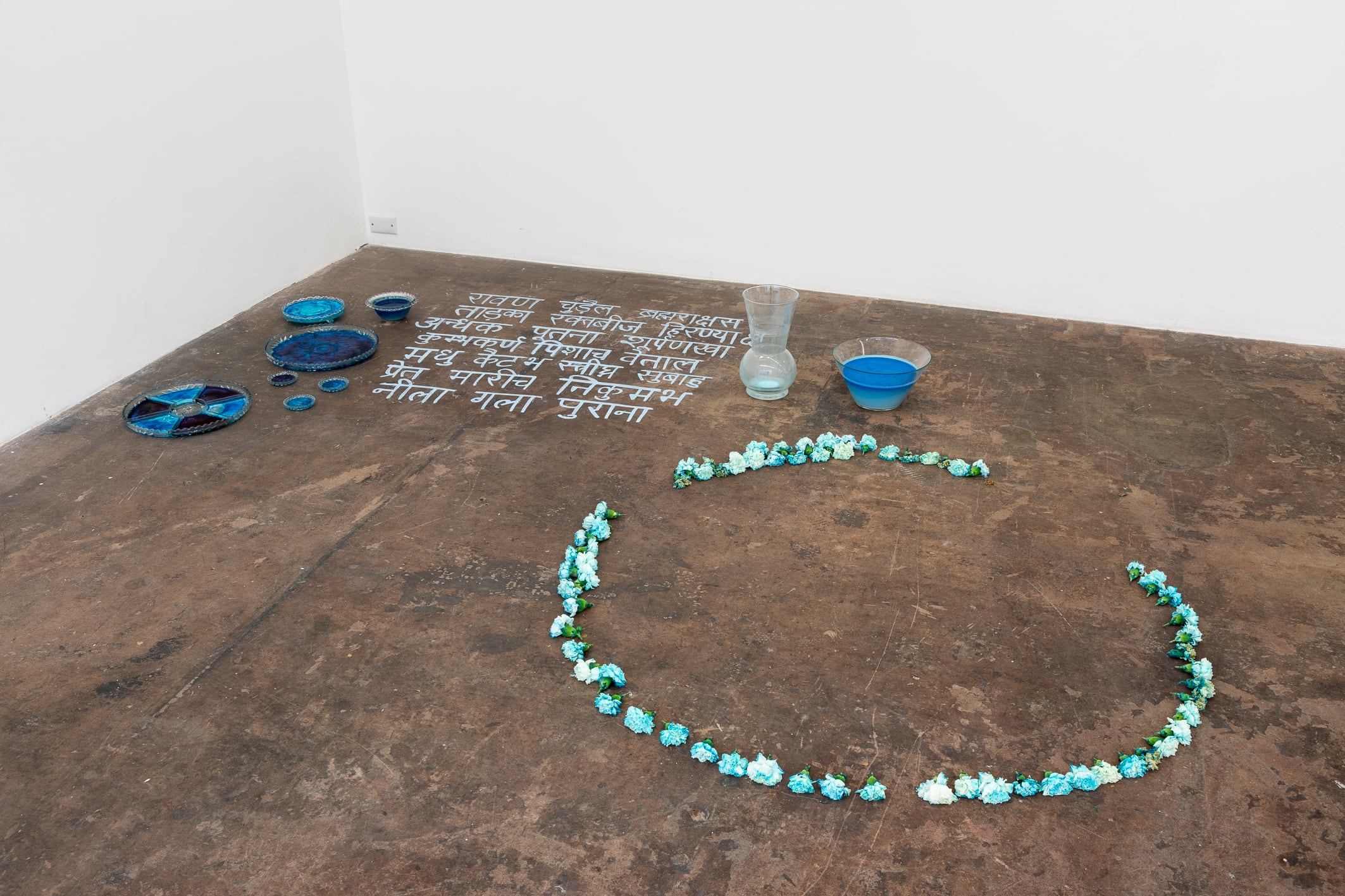

Artists: Manisha Anjali, Natasha Matila-Smith, EJ Son, Rosie Isaac, Angie Pai

Curators: Nanette Orly and Sebastian Henry-Jones

Interview: Anador Walsh

What do you feel unites your two practices? Are there points of overlap that led you to collaborate on I will never run out of lies nor love?

I think we’ve curatorially grown together in the way that we talk a lot about these things, very informally. It’s kind of like an ongoing conversation.

We’re also friends, and we trust one another.

This is the second time we’ve worked on a show together. The first was Nostradamus: a January offering, at AIRspace Projects in Marrickville, in January 2018. It was a show about contemporary rituals. It was kind of techy, but also about the ways that young artists are engaging with the traditions of their cultures.

Tell me if I’m projecting, but would you say that care, collaboration and transformation are central to your practices?

Yeah that’s true, but I don’t make it explicit. I think you just do it subtly.

Yeah, but it’s not the point of what I do, or what I set out to do, it’s more just the way that I conduct my affairs. I make sure that it’s artist-led, directly asking the artist when I engage them what it is they want or would like to get from this experience, not only for their practice but also for their life in general. For example, Natasha (Matila-Smith) had never been to Melbourne before, and that was a really good excuse to have an exhibition with her here at Bus (Projects).

That’s so refreshing to hear. The reason I posed the question that way is because it strikes me that you both work in a way that is very different from the established norms of curating. I think that’s really important and I wanted to highlight that there is actually a way of doing things differently.

That’s a very conscious decision. Our practices have both developed outside of an academic framework and I think that’s really important. Although we’ve both done our Masters (in curating), I don’t think we really utilise that formal education in our practice.

For sure, it’s really interesting actually. One of the first shows I ever did, I read a lot of literature, thought of an idea, then really tried to shoe horn artists into it. But now, like with this show, the idea comes from looking at the practices of artists we really like…

And seeing how they link together.

Yeah, so in that sense it’s not really academic at all. We’re thinking more about the relationships between practices…

And putting the artists first. Maybe that’s what sets us apart, but that’s a whole other conversation. I think I’m probably more concept driven. I generally try and look at artists that work within a concept. There’s always the argument that you select artists, then concept, but who knows what the right way is.

How did you come to language and different embodiments of language? Reading your curatorial statement, the idea of asking for contributions that were either text, performance or spoken really stood out. What led you to that decision?

When we thought of ‘artists that work with language’, our initial idea was text-based work. But the more we thought about how language is embodied or ensnared within a work, how at the same time that it limits us it can be used against itself, the concept progressed.

So rather than it being limiting, you’re highlighting that language has the capacity to be transformative?

Yeah, despite its role within oppressive systems, language is a really powerful tool to reimagine those systems.

How do you see this idea manifesting in the show?

I’ve been thinking about this show more in terms of parenthesis, that grammatical space where anything can be said, anything can happen. The show is about listening to language as much as it is about using language.

I wanted to present works that were quiet and funny, that go against the norm of what you expect a show with a diverse range of artists using language would look like. Like Manisha (Anjali) comes from a storytelling background, which is really huge here in Melbourne — it’s picking up in Sydney too, but I think poetry was really important to include in this context. Manisha’s really great at working across different fields as well, and I particularly wanted to provide her with an opportunity to show with other visual artists, rather than her being contained to the category of poet, because she does so much more for than that. Natasha (Matila-Smith) as well is someone who writes about quiet Indigenous practices and that’s really exciting, and important. It speaks to the idea that if you’re doing a show with diverse artists, you don’t have to make that show about identity. The slower burn, in this respect, is probably the more sustainable one. That ties in with EJ’s (Son) works too. I don’t know of any other Korean artists who are playing around with Korean proverbs in a way that’s funny, but also really, really strong.

Yeah, there’s definitely a temptation with a show of this kind of theme to really explicitly perform identity. You could have an artist spelling out ‘this is my language, this is my background,’ but instead we’ve chosen artists working in a quiet way, a way that’s a reflection of who they are, which is in itself more radical than performing your identity for a largely White audience.

I was reflecting on this actually, when reading the texts that accompany I will never run out of lies nor love. It’s all tied up in the privilege of Whiteness, isn’t it? White people don’t have to perform their identity, because it’s the accepted norm. So it’s really powerful to see a show like this, where the identity of all the artists included (no matter their background) is not performative, but rather just is. Being White allows you the privilege of being able to separate artistic practice from who you are as an individual, whereas people of colour are not often afforded that same privilege. There’s a tendency to conflate the two, but why should identity have to be performative?

Yeah. That’s why our catalogue essay doesn’t describe the works in too much depth, and that’s why we chose to include written responses from people outside of the show. We wanted the entire thing to be about other people’s perceptions of language. That comes under curatorial care, making sure that your voice isn’t the only one that’s being heard. It’s not solely about the curators — or our voices — at any point in time.

This approach seems to be a really powerful way of combating White fragility. You’re modelling ways to change the normal way of doing things, through deference and listening.

Yeah that’s it. It’s crucial not to say too much.

I’d like to bring up Rosie Isaac’s inclusion as the only White artist in the show, which also comes under curatorial care. Just because you’re a person of colour and you’re a curator, doesn’t mean you only curate people of colour into shows. I think if we’re really striving for equality, everyone needs to be represented.

Yeah, the exhibition space isn’t in a vacuum that’s separate from broader social dynamics.

Exactly. I mean if we look at in on the flipside, it’s not like we’d be having this same conversation if a White curator had curated a show of all White people and included one person of colour.

Yeah, exactly.

Rosie’s a really interesting inclusion in this exhibition. Her work is so well situated in this context, it really drives home the idea that you don’t have to perform your identity in order to broach and discuss language. While we’re on Rosie, would you mind speaking to her work a bit?

There’s lots of different ways Spit Trap I, II and III (2019) can be read. If you look at it from a material perspective, they’re kind of harsh, scientific implements that speak to the way that institutional language permeates everyday thoughts and desires. That’s present both in the materials of Rosie’s work and the form, which could be read as a trap.

She did also reference the shape of a museum bookstand, and the way that academic texts trap people and are really closed off.

I think that the inclusion of her saliva in these works is amazing.

It’s a physical embodiment of language, which is awesome.

It’s very beautiful and it almost speaks to something like contagion ... language is kind of contagious.

Which is kind of like this show actually. If two people can curate a show that is silent but very clear of what it is in that silence, then maybe that’ll catch on?

That’s the hope!

What steps have you taken in order to balance the universal and the personal in this show?

I think the publication is a really important element of that.

Yeah, it takes the agency away from us and gives a voice to three people who actually write for a living. We also don’t talk about the works too specifically in our curatorial statement, because some of the work is quite personal. We didn’t feel comfortable talking on other people’s behalf; if these artists wanted to speak about it, they could.

I think it’s the idea of translation, which is actually a really interesting word in relation to this exhibition. How would you interpret Natasha’s (Matila-Smith) work? I would only do so by projecting everything I know about myself on to it. Also, EJ’s (Son) use of traditional Korean proverbs…

They’re so subversive.

Yeah, and people who don’t even speak Korean are fascinated by them.

Without maybe even realising that there’s text on them, They’re just so intrigued by the form. They’re so funny! EJ could quite easily just make traditional Korean ceramics, but she always plays with it and comes at it from a completely different angle.

It would be so easy for her to make works that are just like, ‘I’m Korean,’ but she takes so much issue with traditional Korean culture.

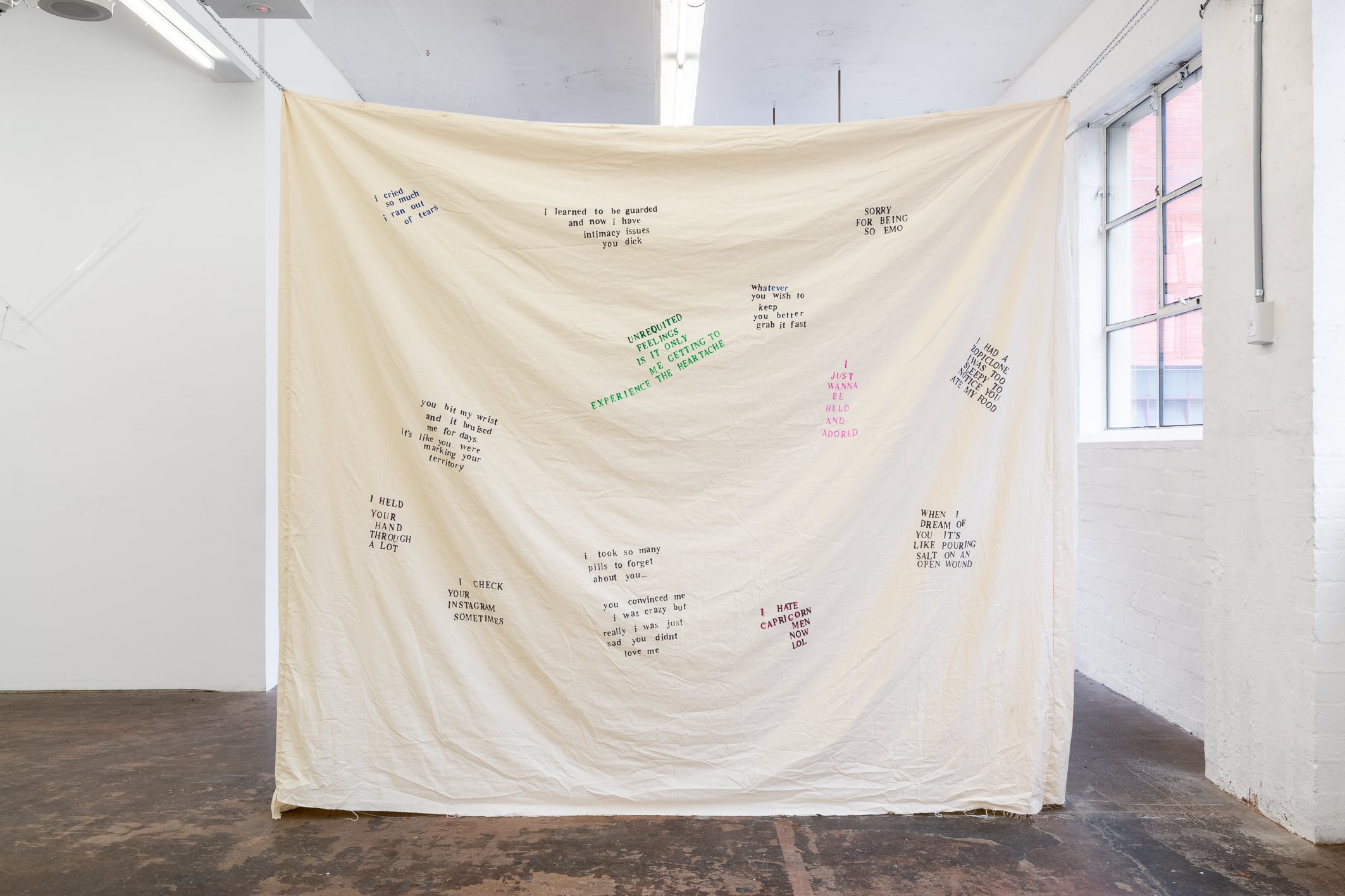

It’s that thing, isn’t it? You’re not expected to do that if you’re a White artist. I love that you’ve chosen not to be explicit. Going back to Natasha’s (Matila-Smith) work, I think that’s what allows such a personal reaction — you can completely project your own personal experience on to it.

Her works are really open and relatable and there’s nothing within that references her cultural heritage either, which allows the work to be seen wholly, without any preconceived ideas based on her background.

Our lived experience influences us, no matter who we are. It’s not something that’s just happening to people of colour.

Which is actually what is really interesting about being a White person in this space. Nothing is explicit and so you’re able to make your own interpretations. By allowing the artists to have their own voice, it’s all very open.

It’s really nice talking about the show, while sitting in the show.

I guess we’ve touched on identity quite a bit throughout this conversation. But I’d like to talk specifically about something you were both involved in, the curatorial symposium Independent Curating // Concepts, Challenges and Collabs at Verge Gallery in Sydney earlier this year. I want to focus on something that came out of your written response (published by Running Dog) Nanette, particularly the idea that the curatorial premise of identity isn’t enough anymore. We’ve touched on it, but I’d like to hear more about how you’ve given your agency up in this exhibition and how that’s contributed to a more nuanced conversation on identity?

Being a curator of colour, I think you come to a point where you’re like: ‘what am I going to do next, what can I do?’ We’ve all done exhibitions about identity, but as a curator of colour it’s necessary to ask: ‘how am I going to push this further and start having conversations that are more specific?’ Identity will always exist, because we all have one, but what else can we derive from this? Looking at institutional exhibitions on identity there seems to be a lack of criticality. You tend to see the same artist names circulated, with works that are very political and loud. When this happens, none of the works actually speak to each other. They’re quite aggressive and the conversation sort of ends there. I’d rather research tiny elements of identity development, because that will always be a part of my practice, looking at specific slippages or connections.

We’re really just giving the artists choice over what they’d like to show, rather than prescribing what we want. Identity as a curatorial concept is a really interesting thing, because when you have an artist of colour who puts an artwork in a show that’s purely about identity, that artwork is read as the definitive word or true representation of who this person is. Which is really unfair, because that artwork was made at a particular point in time, and that person’s identity will continue to evolve. So giving people the opportunity to put in a work they feel works for them, at this time, is something I will always do.

Also, there are artists of colour who don’t want to make work about identity and they get overwhelmed because they don’t tick the diversity box. Which is why I always try and reach out to artists like that. They deserve just as much opportunity as everybody else. In their real lives they are subjected to just as much inequality because of their race, their name, or whatever. Just because they don’t make work about it, doesn’t mean they should be overlooked.

To interrogate that further, it’s the idea that White people don’t have to do that, so why do we treat people of colour this way? after reading the texts and experiencing this exhibition, it occurred to me that I will never run out of lies nor love creates the space to challenge dominant discourses. Can you speak to works in the show that do this?

It’s really interesting to talk about Rosie’s work in this context. As the only White person in this show, I think she thought a lot about her inclusion and her use of language. Her sensitivity and thoughtfulness around her position within the exhibition and our ideas is actually so significant, and an attitude that I hope to embody myself.

EJ (Son) really challenges dominant narratives, and I did notice during the opening people engaging with her work in a really excited way. I think this exhibition is a great opportunity for her to connect with the Melbourne arts community as this was her first show here.

Thinking about some of the other artists we’ve included, Angie (Pai) has up until this point occupied a very different kind of space, one that’s fairly commercial. And Manisha, she comes from the writing world. I think being able to include them in an exhibition space is inherently … radical is too strong a word, but it’s destabilising.

So it’s more of a subtle activism?

Yeah, everything is considered, discussed, and questioned. Which is why it’s been so great to collaborate. You can bounce ideas off one another and critique things, and that’s really important.

I think Angie’s work is really interesting to interrogate from the perspective of identity politics and capital. She occupies this space where there is a monetary value placed on the work that she makes about identity, and so it’s really interesting to observe her work outside of a commercial context.

It’s been really interesting watching her trying to compute what having a show at an ARI is like, and having conversations with her where we aren’t asking her to make work for monetary reasons — we’re asking her to make work that speaks to her. It’s extremely personal, but again, it’s not our story to tell.

I will never run out of lies nor love ran from 10 July to 3 August 2019 at Bus Projects, Naarm/Melbourne.

Nanette Orly is an independent curator based in Sydney. Her curatorial practice is deeply engaged with themes surrounding identity development, cultural histories and offering alternative perceptions of contemporary society. Drawn to migratory aesthetics and research-based practices to form interdisciplinary group or collaborative exhibition concepts, Orly has curated exhibitions across a number of Sydney, regional and interstate galleries over the past five years. Nanette is currently working on a collaboration with Andy Butler for Next Wave 2020.

Sebastian Henry-Jones is an emerging curator based in Sydney. His practice is led by an interest in cultivating strategies of care, social responsibility and shared experience that can communicate across cultural and social differences. He looks to enact these ideals in his work by centering the needs and ideas of the people that he works with, and so his practice is informed by striving for an ethics with sincerity, generosity, honest communication and learning at its core. Seb is a co-founder of Desire Lines.

Anador Walsh is an emerging writer and curator, currently living and working in Naarm (Melbourne).