Exhibition: To companion a companion

Artist: Fernando do Campo

Gallery: Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts

Somewhat negentropically, it takes a moment for the meticulous repetition of motifs and formal logic to register. A tight palette sourced from archive item number 12, ‘Colour Studies’ attributed to James Fredrick Archen, is elaborated throughout the exhibition: from the banners constructed from performance costumes playing on the two screens, to the palettes of the acrylic paintings along with the geometric forms in these reconstituted banners and the painted plywood structures that take their departure from the shapes of the letters in the phrase ‘WHO'S LAUGHING JACKASS?’.

The refined didactics and conceptual rigour make Fernando do Campo’s exhibition To companion a companion a superlative fit with the credo of institutional contemporary art spaces, hence its previous showings at Contemporary Art Tasmania, UNSW Galleries and currently at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art. The meticulous order and polished professionalism conceals a conceit, or is the conceit do Campo wishes to reveal; that which the grotesque Laughing Jackass image signs. It is a reproduction of a water-colour painted in the early 1790s, shortly after the establishment of the British convict colony of New South Wales, that is from a small circle of artists working in the name of science in which the convicted forger Thomas Watling was the most prominent and after whom the collection, archived in the British Natural History Museum, is named.1 The other two or three less talented artists were likely, argues the art historian Bernard Smith, two three naval officers who had some training in drawing. They were working for the Chief Surgeon of the convict colony, John White, a naturalist who was compiling a natural history of the place.

The artist, says the gallery blurb, ‘asks what the avian life around us can tell us about ourselves’. As well as the WHOSLAUGHINGJACKASS Cycle, the exhibition includes 365 Daily Bird Lists (January 3rd 2019 – January 2nd 2020), a year-long archive and record of every bird perceived by the artist, along with a video work of the artist ‘pishing’ for house sparrows: imitating their sounds to attract them.

The archive format of these works and their exhibition is also a type of imitation to attract the contemporary art viewer, its symbolic order having become a defining trope of contemporary art. But what does the archive signify other than the totalising logic of its own order? The work of a con, be they a convicted forger or pisher, should never be taken for granted; but for the easily conned —the patsy — fails to question the symbolic order in which its signs signify (the performance of a con relies on a sense of complacency). This is especially the case for a well-ordered archive such as To companion a companion, which in its name reveals its subject as the archive. As we enter this exhibition, this professionally conceived archive leaves us unsuspecting.

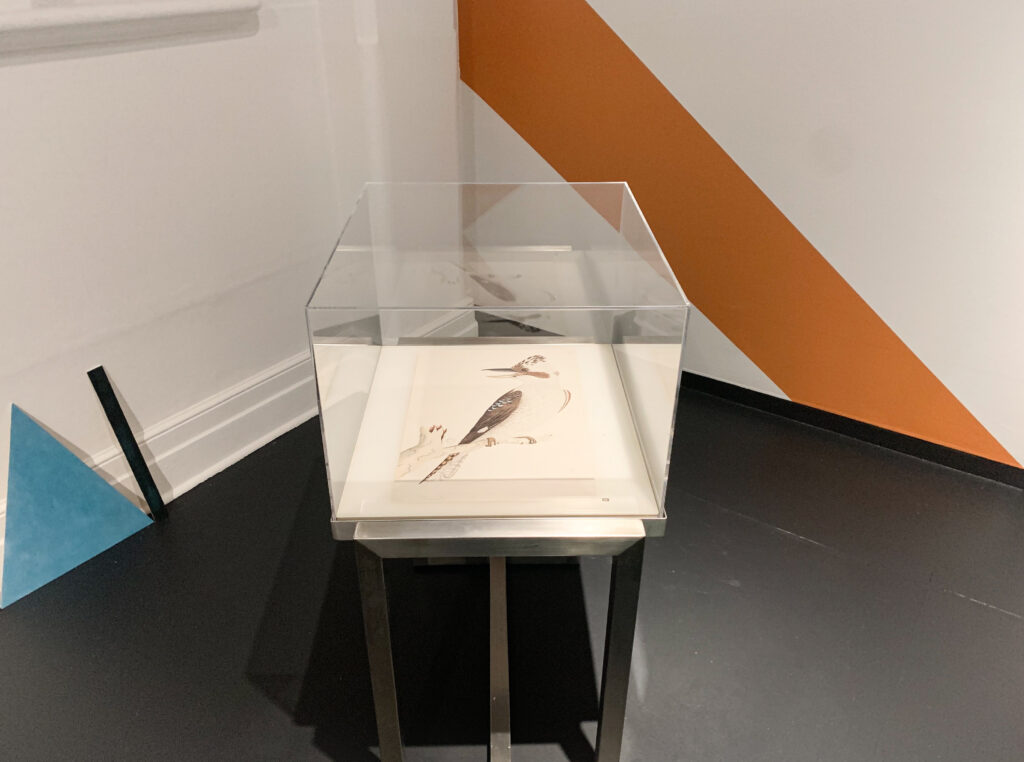

As we are drawn in by the psychogeography of do Campo’s installation, to the vitrine that houses the replica Laughing Jackass, nothing seems out of order or unsettling. Much like do Campo and his plain-cloth disciples in the video works, we continue our leisurely walk, missing the politics that speak to the histories of coloniality, the colonial subject, the question of othering, and asymmetrical relations of power. This lack of interrogation is one welcomed by the artist-cum-conman. Do Campo, in this sense, is a dark Harawaian: 'to produce a patterned vision of how to move and what to fear in the topography of an impossible but all-too-real present, in order to find an absent, but perhaps possible, other present.'2 He pecks holes in the map he draws, draws lines over lines, so that they lose meaning. With each stitch and stroke of pigment, do Campo exalts their ability to manipulate the transcendental symbolic structures that order their signification; to de/re-construct them so that they sing a simulated birdsong that is the not quite truth (but it will do because the truth conceals its truth).3

Do Campo's carefully curated avian archive parrots an excess of carefully placed gossip. He provides new modes of companionship to the non-human. This mode of companionship becomes — via the curation of birds — the non-human imperial archive: a distortion of what Jane Lennon calls the 'mass collection of information'. His archive is a canary in the mines, a warning that might lead the audience to think and look again for a truth that escapes its documentation.

To exalt the untruth, is in itself a grotesque act. In the normative symbolic order of the enlightened world, the grotesque is a perversion of reality but this neglects its generative function. Ultimately, grotesqueries make the othered present, the unknowable knowable (a relationship is thereby (de)formed). The trope of the Grotesque is predicated on its more attractive twin: the idiomatic (in this case, English) Picturesque. In alluding to an aesthetic system integral to colonialism's ideological and economic regime, do Compo’s understanding of coloniality in To companion a companion need not directly speak of colonialism.

The Picturesque is more than an English affectation upon pictorial representation. Products of enlightenment thinking, English artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries — from the ‘metropole’ and the ‘periphery’ — were reared on the visual language of the Picturesque. They utilised the Picturesque, the Grotesque, and the Sublime simultaneously as a repertoire of tropes, producing meaning through their oppositions as if it was a language with which to think. Artists spoke with it to provoke meaning through landscape in an attempt to ontologically relate to it. The Australian grotesque of British colonial artists is a device of othering and connecting that shows, at the least, an abiding interest in otherness. The Kookaburra, the most non-English of birds, is entirely lacking in English propriety, and for the recently arrived English, typical of the upside down world they believed they had landed in. We can imagine that for Watling and his circle that the Kookabarra and its garrulous, mocking laughter accentuated the absurdity of the colonial project to which they were bound.

The real laughing matter is the lack of likeness of the Laughing Jackass to an actual Laughing Kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae). With its grossly elongated neck, augmented crest feathers, disproportionately large beak, and overly expressive face, Laughing Jackass appears as an image of distortion. Watling’s training as a miniature portrait painter led him towards the caricature or exaggeration of facial features to impart a sense of individuality; in order to make his subjects recognisable (knowable). The other artists in his circle tended to idealise and so de-individualise their subjects, making them into types rather than individuals – which is why it is believed the Laughing Jackass is not by Watling but one of his circle. Despite the lack of precise authorship, it is a grotesque para-fiction of an anthropomorphised antipodean landscape.

It is almost as though do Campo proved himself wrong and then right in each of these works. Firstly acknowledging our normative expectation of the hierarchies of knowledge posited by the archive format and then denying them in 'a cheeky ode to the winged companion that flits among us', that is to say, a para-fictional larrikinism. As we the audience accept do Compo’s presentation, we re-perform its perverse constructs; we adhere to his glossectomy of the Kookaburra. But in doing so, we perform our own glossectomy and suture our tongues in its place, into the corpse of the laughing Jackass, frozen in its place by an order held behind the brittle, glass membrane of the vitrine.

To companion a companion conceals what it evidences in an archive or index that (dis)orders its order. Given do Campo’s commitment to his archival project evident in its professional rigour, this ambiguity appears strategic. His is a conceited archive, one that through interrogation becomes unknowable. An archive that can construct its own possibilities through its numerous ‘failures’. The exhibition offers no promise of posteriority, substituting in its place a multiplying mess of relational detritus: fragments of text, flesh, and strangled voices. Ha ha: the laughing jackass will have the last laugh long after our last meal. Does this elaborate shell game beguile the audience into affirming that which the exhibition warns against: the arbitrariness of the archival impulse?

Were we just conned?

Perhaps it is true for all art… one should proceed without caution, love contemporary art with its trickery and gossip, just so you can hate it properly.4

Lévi McLean is a researcher, writer, artist and art centre manager working in the Northern Territory. He is undertaking an Honours in Art History at University of Western Australia. He has worked in a variety of roles with The Tennant Creek Brio and is also a part of the experimental art collective mg.g.M.Mg.MG.

Chandler Abrahams is an artist and writer working in Boorloo. Their research engages with ideas of world building, spatial narrative, and power in contemporary systems of control. They are also a part of the experimental art collective mg.g.M.Mg.MG.

un Projects’ Editor-in-Residence Program is supported by the City of Yarra.