This is the second of a two-part conversation series between Sophie Rose and Utility, an ongoing collaboration between sound artists Austin Buckett and Thomas Smith. You can read the first part here.

Describing the project as a shared fascination with the ‘existing constellation of fake and real sounds’, Smith and Buckett draw from the seemingly-infinite library of presets in electronic music production. Situated somewhere between authorless readymades and original compositions, these presets increasingly inform popular music and, in doing so, expose something of contemporary culture at large. Their latest release, Nexus Destiny, is a collection of sixty short arpeggios made exclusively with such presets. Complicating the dichotomies of original and copy, inspired and derivative, expressive and mechanical, Nexus Destiny unpicks the complex intertwining of software, creation and affect in a digital age.

Sophie: Is an etude a kind of readymade then, in the sense that it is ownerless and repeated? Of course, a preset is also without an author in this way.

Thomas: It's true presets are authorless in the sense that they can be re-used and not attributed, but they do have authors. Sometimes software instruments credit the authors in the interface, and some sound designers are known to producers. For instance, an engineer named Mike Daliot who works for a German company called Native Instruments wrote many of the presets that defined more commercial versions of dubstep, that then informed the genre of EDM. But yes, we definitely see our work as straddling a zone between older conceptions of authorship and some version of a readymade. These presets, with their pre-determined timbral and spectral characteristics are widely available, and we have really just assigned them notes and framed them for people to listen to for their own sake and/or to reuse as producers.

Austin: There’s a growing trend towards the distribution and re-use of materials especially in trap — or what is now pop music, really. Online, subscriber-based sample interfaces like Splice, and Native Instruments’ expansion interface Native Access are evidence of this. A big influence for us is an interface called freesound.org which is a user-generated repository of samples — this idea of a musical culture which revolves around archives or databases is part of what we’re trying to examine. There are artists whose main area of work involves this type of work: distributing samples to be included in productions. For instance, a producer called Mario Luciano is known for creating sample packs used frequently by producers like Kenny Beats; or German production duo CuBeatz, who are known for sending samples to Canadian producer Murda Beatz who used them to create the Nicki Minaj/Cardi B/Migos’ hit ‘Motorsport’. Likewise, an action or technical approach to a sound can become a presetor standard that is traced to a particular author. For instance, Toronto producer Wondagurl’s sliding 808 bass has become an identifiable standard that marks a certain sub genre. So there is a kind of authorship that is always retained, even when the contents of a database are the building blocks of music.

Sophie: So unlike, say, musique concrète and it’s followers, your readymade sounds do link to real people. Is part of your project revealing this network — tracing the provenance of trap-cum-pop songs to an unseen archive?

Thomas: We have something in common with Schaeffer et al in that we’re examining recordings, or ‘sound objects’ as they put it. They were trying to figure out what happens when sounds are separated from their origin, and to make a practice around this. But you’re right we’re taking an opposite approach by sort of reinscribing sounds with a context — there is no pure recording without context or meaning because sounds are always used and experienced socially. So yes, our work is partly about finding patterns of continuity within an archive of sounds that when viewed as a totality appears endless and anarchic, but that also manifests socially in the form of generic musical aesthetics that are familiar and identifiable. I think this is how we collectively make sense of an archive that is so huge it sort of confounds perception; certain parts of the archive are collectively selected as being meaningful. In the case of Nexus Destiny, we’re putting forward a tiny slice of this archive as a kind of still life. We could make thousands of records like this and not even scratch the surface in terms of the amount of sounds available to producers, and yet there are certain presets among these that have become very identifiable and appear everywhere.

In this way, I think a collection of synthesizer presets encapsulates a certain contradiction around the way computation has been applied to ‘creativity’. The software industry enforces an ethic of endless production through the proliferation of ‘powerful’ tools, and yet there is only room for a certain amount of sounds in the popular lexicon at any one time. Despite the emphasis placed on innovation and newness in neoliberal economies, at the level of consumption music needs to change at a certain pace in order to retain any meaning. So for me there is a kind of sociology of technology going on in our work, where music production offers a clear set of parameters for understanding the way computation and networking has been applied socially.

Austin: It is interesting to think about how musique concrète might relate to this project. Schaeffer’s concept of ‘reduced listening’ talks about his recordings of trains being looped and manipulated to the point of departing from the origins of their sound source. He talks about making recordings ‘where the train must be forgotten and only sequences of sound colour, changes of time, and the secret life of percussion instruments are heard.’ I think to an extent Nexus Destiny might have this effect on the listener. Where through recontextualising sounds that might

usually be heard in the context of a broader song with other instrumentation, and through looping these single-line, melodic structures there’s either a choice to switch off from them as compositions in and of themselves, or to lock into the intrinsic characteristics of the sound as opposed to a context. There’s a sort of aesthetic fragmentation that’s occurred in relation to these contemporary trap/pop production synth styles. Through presenting something in an archival format for reuse it is inherently unfinished, and this open ended-ness means that there are these embedded possible futures within each track relating to how these rendered sonic characteristics will apply to future contexts. I feel like there’s something strangely, digitally melancholic about this aspect of the record, they are sounds and tools that have been generated but can never quite rest as completed works.

Sophie: Perhaps a good question to end on is how you perceive your own role as ‘authors’. What do you create through harvesting the ever-expanding database? And what’s on the horizon for Utility and the archive?

Austin: I have a background performing and composing music in more traditional settings, and I’ve always felt uncomfortable about this notion of the composer as an enlightened author pulling sounds out of the air in a fervour of inspiration. For this reason, I’ve been apprehensive about

talking about my creative process in interviews, but more recently I’ve wanted to examine process as a starting point to generate new works. There’s something inherently flawed about describing your own creative process, there’s always a slippage or a distortion involved. In a sense, as Utility we make music about making music, or about how we traverse an archive and put ourselves together. I enjoyed this book called Archive Everything by Gabriella Giannachi recently that speaks to this. She thinks the archive is central to how we build ourselves, that we augment ourselves through it, and that it re-creates a sort of indexed version of life.

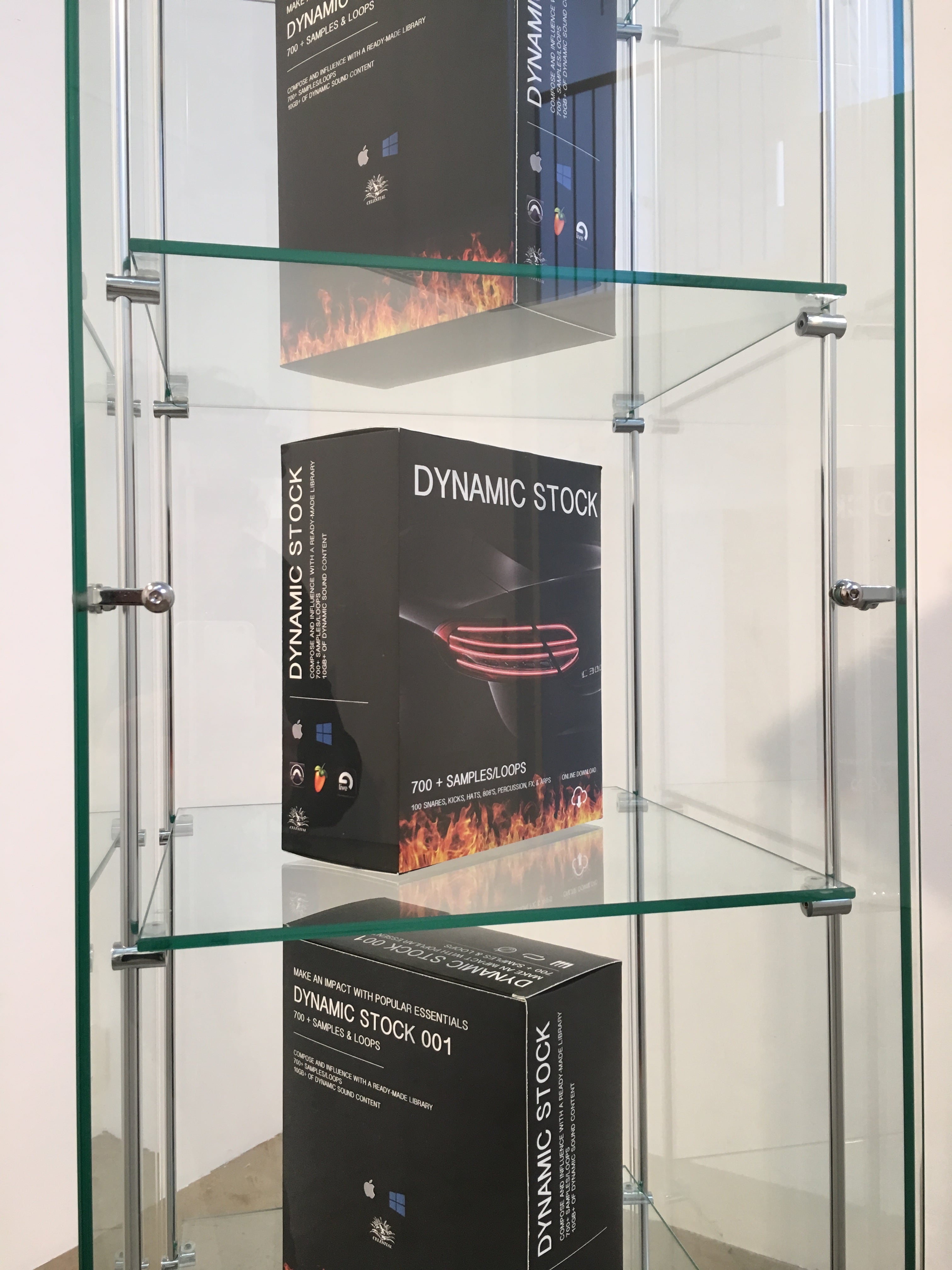

Late last year I had a collaborative exhibition with Coen Young titled Strategic Innovation that explored this more, at Kronenberg Wright in Sydney. I made some works exploring the aesthetics of sample packs. In one of the works I was looking at how these sound collections are almost always presented as physical objects, despite being a folder of downloadable .wav files. They’re always presented as software boxes on a white background, with artificial shadows and gaudy bold text. I wanted to reverse this simulation by manifesting these digital collections as physical objects.

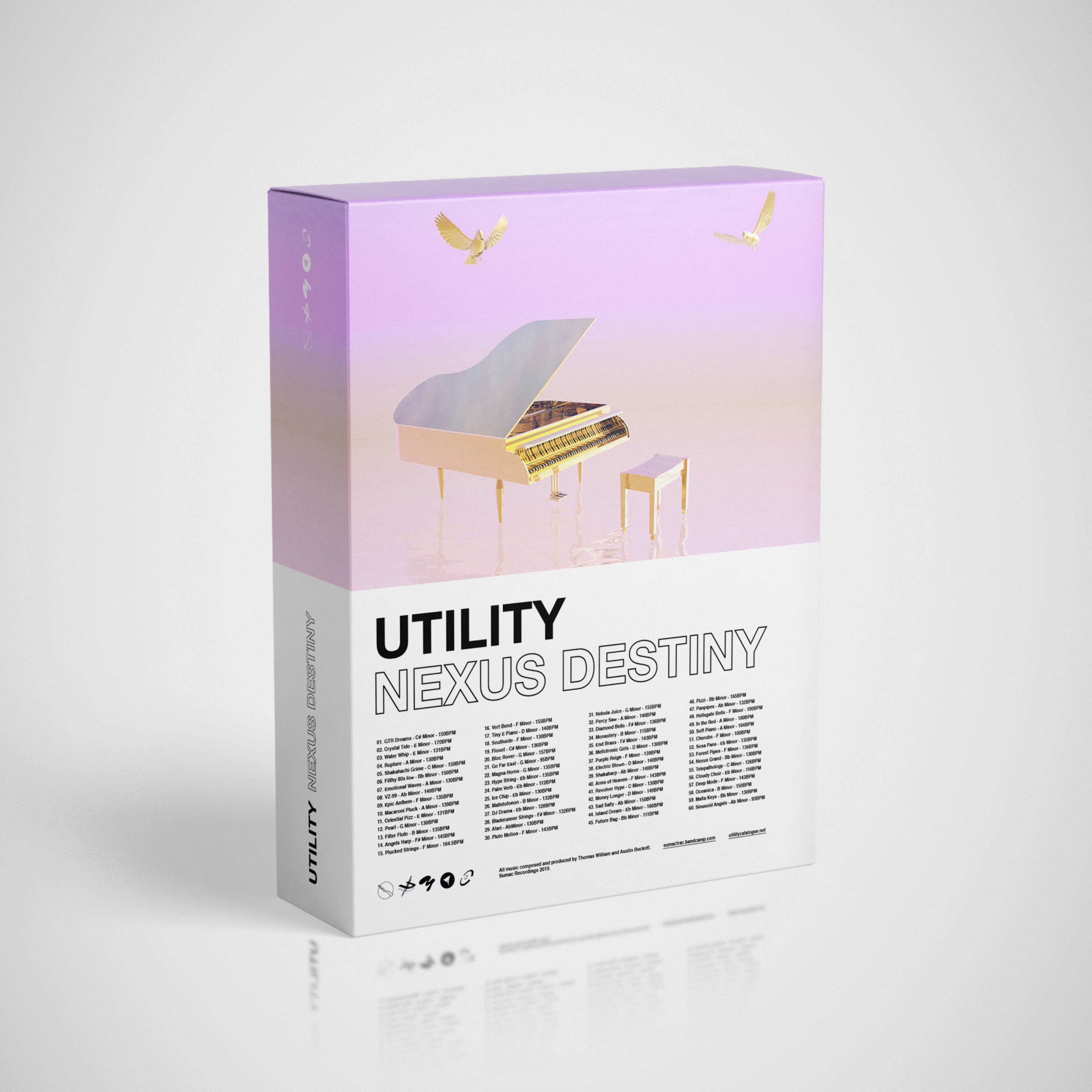

In some ways, the idea for Nexus Destiny came from these boxes, and the design for that piece, which I worked on with Tom, directly informed the Nexus Destiny cover art (put together by a designer named Thomas McAlister). I wanted to explore a contradiction between differentiation and standardisation that is probably somewhere in all our work. Audio sample packs embody this in that they are collections of pre-existing material to be used in the creation of something new and different; they confound authorship at the same time as they are predicated upon it. The title is a reference to this: ‘dynamic’ refers to changeability, particularly in relation to loudness and softness in music. Whereas ‘stock’ refers to products that are always the same and can be used over and over, such as samples in music production. I wanted to broach this paradox where something can be both dynamic and stock; musical authorship seems to always contain something of this paradox and I want to keep exploring that.

In terms of Nexus Destiny, we will have a collection of remixes coming out over the next few months from different artists, and apart from that we’re continuing our various production collaborations, working on some club music, writing beats for several rappers, and we’ve been working on audio-visual pieces for more of an art context that we plan to develop at a couple of residencies next year.

Thomas: Some people think of music as a kind of subjective force that bursts forth from one human and is transmitted to another, but it is also a kind of mathematical system, or an organising principle. Of course music is both these things: no matter how efficient and computerised its production becomes in a digital context, it always functions according to both these criteria. So I’m interested in the tension between a technologically-determined view of music as a set of parameters on the one hand, and the emotions and experiences it always carries on the other; no matter how canned its production might appear. Authorship is always an artefact of this tension for me, so even though Nexus Destiny draws on all these standardised production processes, it’s still a personal thing. It’s meant to be listened to and felt even though we have been thinking about in these ways. I have never really subscribed to a modernist or avant-garde ethos that sacrifices those kinds of experiences, so above all I hope people like it. But I also want to create work that brings a certain perspective to music as a technological assemblage that can be analysed, and that can tell us things in a way other mediums can’t.

Sophie Rose is currently Assistant Curator at the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA).