Fiona and Sidney Myer Gallery, Melbourne

Gabriella D'Costa, Christina May Carey, Julien Comer-Kleine, Kate Wallace, and Skye Malu Baker

Curated by David Sequeira and Hee Joon Youn

1 - 30 September, 2023

The bureaucrat has flown the cubicle, headed oceanside. Artist Gabriella D’Costa is in motion, departing Melbourne’s city grid on a pilgrimage for sediments and sea beads to inform a body of work commissioned by the Fiona and Sidney Myer Gallery. The gleaning destination is Ricketts Point where intertidal rock pools stipple the sandstone shelves between sea caves that hold D’Costa’s formative memories of swimming. Here, the south-eastern cusps of seaside and suburbia often bear a social history of extensive rail commuting, seasonal church attendance and Catholic schooling. D’Costa’s oeuvre has sustained hallmarks that recall these prosaic spaces instantly. Wood grain veneer, wobbled Word Art photocopies and chairs upholstered with flecked carpet are elevated beyond the substrates of nostalgia; utilitarian liturgy acknowledged. The artist's latest approach warps these motifs of ad-hoc literality through an esoteric magnetic filter for presentation in a group show curated by David Sequeira and Hee Joon Youn, opaquely titled Making the Invisible Visible.

Fortuitously, D’Costa re-commenced swimming soon after receiving the commission, frequenting the City Baths. Through meditative observation of the way liquid and light interacted there, they were spurred to create an illuminated science experiment that stacked household liquids by order of density into an abject trifle. Continuing to test how various fluid compositions would interact with non-liquid agents such as iron powder and magnets, D’Costa expanded on the kinetic potentialities they had uncovered through magnetic orbs in their show Motion Holders at Blindside last year. Ferrofluid, a colloidal liquid containing magnetised iron nanoparticles, is rare and therefore expensive. D'Costa moonlit as a mixologist in their Nicholas Building studio, conjuring a solution with enough mineral oil to control the iron powder’s behaviour once exposed to magnets. When I visited, the bootleg ferrofluid was in its leaky infancy and magnetic neodymium sheets had been cut with such precision that it caused the artist a repetitive strain injury.

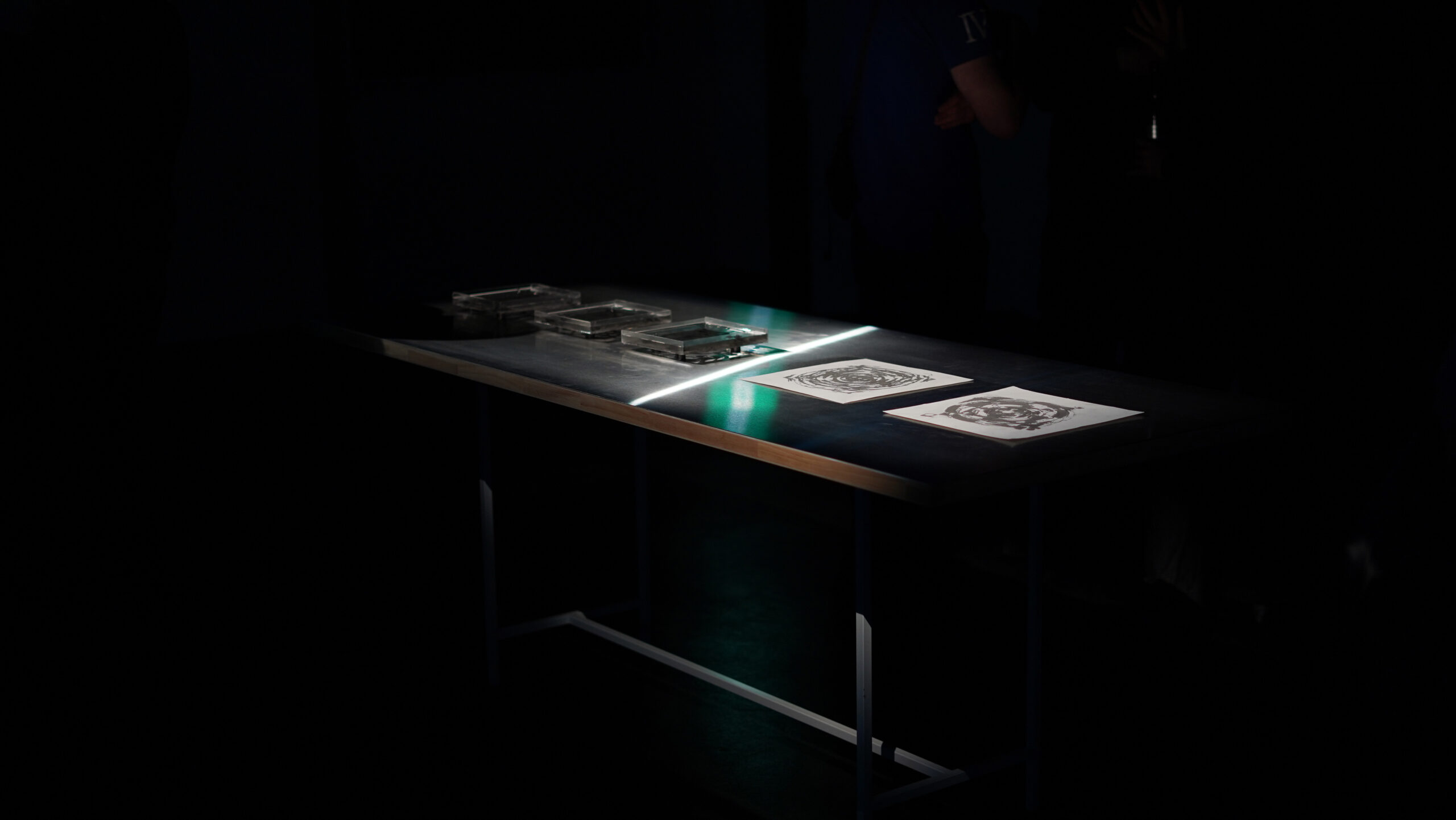

At this stage, D’Costa’s artistic process was observably feverish. They hovered over a metal work-surface like static, sublimating a period of personal upheaval into a cerebral challenge. To access the undercurrent, they revisited their adolescent haunt Ricketts Point to gather themselves, amongst other materials such as sand, soil and water. The edible sea beads that encrust the rockpools there recall a ‘bead maze’ motif that has been repeated throughout their prior work, carried into the show via petri-dish-esque artwork Neptune’s necklace. It sits open atop a metal sheet, illuminated from above as though awaiting microscopy. It’s one of three kinetic sculptural drawings housed within clear perspex containers constructed to contain the hand-mixed ferrofluid. The neodymium sheeting inlaid at the bottom conducts the iron filings into a protruding corrugated silhouette. The second dish, Walking Clef, splices a calligraphic image into the striations of a tectonically shifted fossil. Lastly, Futurama submerges a dream-coded drawing that emerged from D’Costa’s illustrations for the planner they publish arbitrarily each year, recalling the dimensionality of Op-artist Victor Vasarely’s ‘kinematic’ images.

Photo: Carmen-Sibha Keiso, courtesy the artist and Fiona and Sidney Myer Gallery.

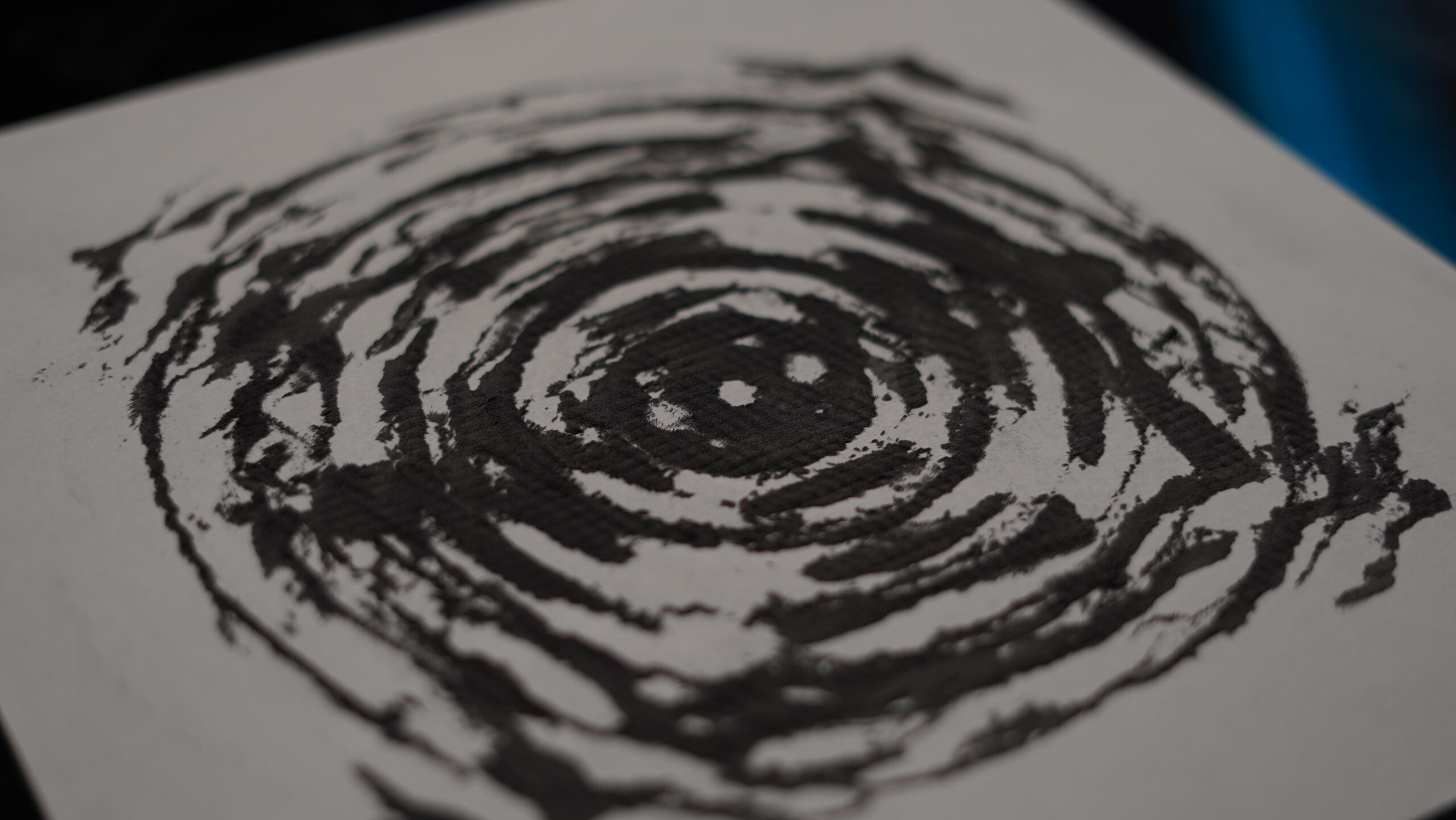

Beside the ferrofluid vitrines, pigment blurs across the surface of two works on paper in a runic, henge-like pattern. Their occasional blotting suggests ink has been blown out into Rorschach tests. Looking closer, it’s apparent that dark iron particles have spiked upwards into mini-lithic cities, held in place along fine grid lines by the magnetic forces within the unseen neodymium beneath. The kinetic surface texture seems soft to the touch; a chenille fabric raked like a zen garden. During an informal group critique prior to the show, artist Yuval Rosinger distinguished a prevailing religiosity in these pieces that contrasts with the aforementioned dishes’ secular appliques. Later at the exhibition's opening, an enthusiastic patron lifted the aptly titled work The philosopher’s stone is found in the dung heap above the magnetic field – perhaps hoping to reveal some prophecy beneath – and defaced its iron powder formation. Fortunately, the work’s kinetic quality allows infinite resurrection and forgiveness of sin. D’Costa merely brushes the powder back across the surface.

The graphics themselves are Orphic abstractions of sacred geometries with a quirked Global Village Coffeehouse sensibility that overrides any vacillation into Modernist mustiness. The powdery, orbed forms suggest the sensory affectation of a subwoofer’s vibrational bounce, bringing to mind a 2007 5 Gum commercial – or the geometric visualisations of sonic frequencies that Ernst Chladni made by drawing a bow across the edge of a metal plate of sand in the 1700s. This energetic effect was coined ‘cymatics’ by physicist Hans Jenny in 1967, meaning ‘matters pertaining to waves.’

Given the encompassing nature of cymatic pulsation, we all swim through each other's waves constantly. At the opening of Making the Invisible Visible, wedged within one of the University of Melbourne’s constant construction sites, Julien Comer-Kleine’s neon tubes sputter overhead as they receive frequencies emitted by the chatty whirl of attendees and staff after their solid week of industrial action. These fluorescent, sociological Geiger counters flicker faster as the room fills; the argon gas ionising erratically inside the unevenly bent glass tubing. In contrast, warm light precisely frames Kate Wallace’s pint-size oil paintings. Locket-like, they quietly confess to a viewer up close. The deftly applied details of aerial landscapes and dappled nature scenes undulate to the rolling bass soundtrack that accompanies Christina May Carey’s wall-sized video work Embodied Tendencies. In frames of a butterfly’s wings beating and an ombre screensaver-style render, her signature royal blue casts a cool hue throughout the otherwise dark gallery, only interrupted by rapid-fire flashing that warrants an epileptic warning. The work draws me in and out, a pulsation without pathos. As I go to exit, Skye Malu Baker’s Gates and Gates stands stalwart, an whorled iron frame containing a monochromatic Terre Verte (green earth) pigmented painting, giving it the air of a mediaeval real-estate board. The shadow it casts stretches as though it’s a hallway carpet beneath my stride.

I left the cavernous room feeling that I could take any direction and end up returning; a dizzying hermeneutic loop of philanthropic resources, institutional narratives and alumni artist development never quite arriving at a definitive conflux. To quote Audrey Schmidt’s written accompaniment for D’Costa’s work, it’s a ‘world within a world’ a liminal heterotopia where time is askew. The show is testament to the evolution of the artists, who were each gifted a small potted money tree during an introductory curator’s talk, but beyond its walls, the gallery seemingly doesn’t yet have a platform to engage with the fruits of their labour. I await the loop slipping open to draw us all in.

Ella Howells is an artist and writer on unceded Wurundjeri land.

un Projects’ Editor-in-Residence Program is supported by the City of Yarra, Creative Victoria and City of Melbourne

Editor: Carmen-Sibha Keiso