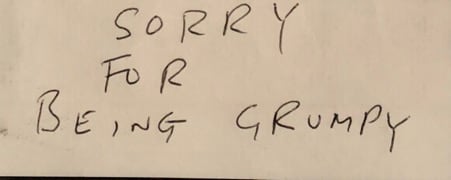

SORRY

FOR

BEING GRUMPY

Standing alone in Te Puno O Waiwhetū (Christchurch Art Gallery), I snapped this detail from Marie Shannon’s work and sent it somebody (text accompaniment: ‘NOW THAT’S WHAT I CALL: art’). It was meant to be a kind of witty apology – stealing someone else’s words to make light of the kind of everyday tussle that comes with relationships. Especially ones that are all about texting:

‘Are we okay?’

‘What are you up to?’

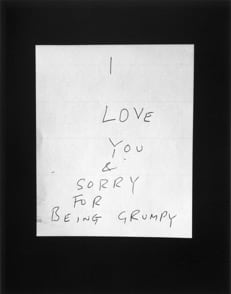

Above the apology for grumpiness, Shannon wrote:

I

LOVE

YOU

‘I love you’ is the kind of thing we text, or say, or write to another person. It means something between you and that person but you both know it’s kind of, well … trite.

I remember in first year uni all the classes we had with ‘postmodernism’ in the title would tell that same story about how ‘I love you’ is meaningless in the time of Jackie Collins fiction. It was something my friends and I could predict in the first couple of weeks of class. Here comes the Jackie Collins thing … (collective, cynical, 19-year-old groan). Attributed all sorts of ways – it was Baudrillard, it was McRobbie, it was Derrida. I still don’t know. But you get the point. Maybe it’s that words, when repeated, become word salad and miss their mark. Who would be so uncool as to say ‘I love you’?

But the story about Jackie Collins worked the same way. It was repeated over and over until it became kind of meaningless.

Here we go again – the Jackie Collins / ‘I love you’ analogy.

Marie Shannon’s exhibition does something different with words and images which, at first glance, might be considered banal or, repetitive or ‘light’ (although what could be lighter than romantic fiction?)

Now that I think of it, lecturers never said ‘Jackie Collins novels’.

Shannon navigates the everyday in her photographic and video works. The exhibition is called Rooms found only in the home – a suitable title, as most of her work reflects on domestic spaces. Shannon makes small models of rooms and populates them with people made out of pipe cleaners. She catalogues the things found in bedside tables and drawers. These ordinary things which we might not always notice take centre stage in Shannon’s artworks. She doesn’t ‘flip’ these ordinary places and objects and make them portentous, however. They simply are.

Was the implication in the Jackie Collins riff my lecturers made that we needed to be more portentous, serious and heavy?

Shannon’s art, conversely, works as an example of what Kathleen Stewart calls ‘ordinary affects’. Stewart, alongside Lauren Berlant, Michael Warner and others, consider how these sorts of ungraspable ‘feelings’ (for the present purposes shorthanded as ‘affects’) circulate and produce our world. Stewart notes that cultural representation often looks for the big event, the big structure, big system (or big ...) as some kind of decoder ring for why things are the way they happen to be. What this approach misses, she writes, is how we experience a ‘reeling present’ – how it is the everyday – ordinary – interactions which move between the domestic and the public that work to produce the big things we might label ‘neoliberalism’, ‘hetero-patriarchy’, etc. They are ‘public feelings that begin and end in broad circulation, but they’re also the stuff that seemingly intimate lives are made of. They give circuits and flows the forms of a life’.

There’s something in Shannon’s work that attends to these circuits. It reels, too. The scene is mostly her home in Auckland, but her work hums with various practicalities and obligations of the (big?) ‘global art scene’. Her partner achieves a residency in Aachen, Germany. (You can almost hear the conversation – ‘It’s a great opportunity for your career ... I’ll stay behind ...’) She records his absence through The Aachen Faxes – transcriptions of excerpts from faxes (his trip was in the 1990s and prior to the advent of email) from him to her. We know little of what work he is making or even about the residency. The faxes loop on the ordinary:

I forgot to say, yes put the $500 from the Falcon towards a new car

Have you taken up the hall carpet yet?

When she includes sentiment (I love you and think of you all the time) it sits within all the ordinary parts of how we might build connections in the contemporary context – through mundane exchanges about shared property and even how the fax, the text, the symbolic is never quite enough. ‘We feel its pull,’ writes Stewart, but representation ‘falters, fails.’ A section of The Aachen Faxes describes Shannon’s partner trying to learn to touch type:

I embarked on a series of exercises. In fact tonight is the first night I have actually tried to type anything apart from f j f j f j f j f j f f j.

The repetition makes ‘word salad’. Maybe.

I think of you all the time, and I have your photo up where I can always see it.

The text stammers in the repetition of his affirmations of love for Shannon – placed among accounts of art openings where he feels everybody is smiling, but he is disconnected. Again, words fail to match the affect:

Talking on the phone is always hard. First you have to find a phone, and then people come in and look at you talking.

Shannon’s other works address the circulating forces that perhaps become hard-wired in the artworld. Institutions aren’t solid but constituted through what Stewart calls ‘forms, flows, powers … encounters, drudgery, denials, practical solutions, shape-shifting forms of violence.’ She satirises the taken-for-granted importance of a solo show, or a touring show, in The Karaoke Tour of Sydney:

THIS WAS ANOTHER PROJECT I THOUGHT ABOUT DOING FOR MY SHOW AT CBD GALLERY IN SYDNEY. I WAS GOING TO DO AN ART PERFORMANCE WHICH WOULD BE ME DOING KARAOKE SONGS AT DIFFERENT VENUES AROUND SYDNEY. IT WOULD BE THE SAME SONG AT EACH PLACE, OVER FOUR OR FIVE NIGHTS; THE NAME OF THE SONG WOULD BE THE NAME OF THE TOUR. SO I WOULD DO THE TOUR IN THE WEEK PRECEDING THE OPENING OF THE SHOW, THENGET. AT-SHIRT PRINTED WHICH WOULD BE LIKE A ROCK-BAND TOUR SOUVENIR. LIKE THIS:

THE SOMETHING SOMETHING TOUR

MARIE SHANNON IN SYDNEY

CBD GALLERY JULY 25TH TO 31ST

AND ON THE BACK, THE VENUES AND DATES OF THE PERFORMANCES. THERE WOULD ALSO BE A VIDEO OF EACH PERFORMANCE WHICH WOULD PLAY IN THE GALLERY. THE THING IS, I’VE NEVER MADE A VIDEO BEFORE, AND I REALISED, IT MIGHT NOT WORK AND I WOULD BE LEFT LOOKING SILLY. ALSO, BY NOT HAVING TO DO THE PERFORMANCE AND MAKE THE VIDEO, I HAVE MORE TIME TO DO OTHER THINGS.

There’s nothing worse than looking silly – right? Those ‘other things’ might be serious things, the heavy lifting of ‘making-it-work’ in the art scene. We go back to the Jackie Collins riff – the lightness of repetition; singing somebody else’s song in a karaoke bar. But couldn’t art exhibitions also be just ‘Something Something-s’? A type of circuit which hardwires particular ways of being in the world through installs, openings, networking, de-installs. Stewart writes about this as a type of ‘mainstreaming’ of ideology, that we must be ‘in tune with a “something’ that’s happening”’.

I sent a photo of The Karaoke Tour of Sydney to an academic colleague thinking about how karaoke is part of the conference circuit, too. How well you sing ‘Material Girl’ with that big-name professor from America might mean as much as the ‘Something’ you say in your conference paper. As it happened, my colleague took the same photo when she saw Shannon’s exhibition.

The thing about ordinary affects is that they resonate – sometimes those things which look light and ephemeral are the very things which mean we flourish or fail; sag or succeed.

Looking silly might be riskier than you think.

Rosemary Overell is a lecturer in the Media and Communications at the University of Otago. Her most recent work considers how gendered subjectivities are co-constituted by and through mediation. She draws particularly on Lacanian psychoanalysis to explore a variety of mediated sites. In particular, she considers the intersections between affect and signification and how these produce gender. Rosemary has looked at media as varied as anime, extreme metal and reality television.