Artists: Tony Albert, Rushdi Anwar, Sophie Cassar, Tabita Rezaria and Liz Linden.

Curators: Georgie Meagher.

Is it a measure of resilience to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick biosphere?1

Within a biosphere subject to an entanglement of hyperobjects – white supremacy, patriarchy and climate change, just to name a few - finding ways to cope and nurture our resilient side seems like a logical and positive step. But what do we really mean by resilience? And is it enough to counter this amassing complexity?

Octopus 17: Forever Transformed, the first exhibition at Gertrude Contemporary’s new premises in Preston and the 17th incarnation of their Octopus series, brings such questions to the fore. Curator Georgie Meagher doesn’t bring us consensus, but instead offers a reflection of the complex world we love to love and love to hate, and perhaps wish would love us a little more.

Through a distinctly feminised lens, both Liz Linden’s and Sophie Cessar’s work are a reminder that resilience is not about taking the path of least resistance.

Linden’s Damaged Goods (2016) presents a range of different book covers all bearing the title of the artwork. The repetition of this phrase and all it implies caused my female body to sigh in recognition. Images that would usually nestle in the readers’ hands are almost life-sized on the wall, lending the works a surreal quality. Rather than operating as simple evidence of a patriarchal status quo, the enlarged covers – all featuring images of women – become a sort of parody, rendering the realities of the patriarchal gaze almost laughable. I say almost laughable because this is not a fictional world created by the artist but fictional worlds circulating within the patriarchal reality beyond the gallery.

Linden’s Damaged Goods shares the space with Sophie Cessar’s installation Little girls love to cry so much that I have known them to cry in front of the mirror in order to double the pleasure (2017). A white laminex table and bench flanked by three plinths trimmed with tones of baby blue and pink faux-fur and ribbon are topped with toy mirrors and small glass talisman forms. Small books, most of which are handmade, sit in matching stands arranged on the table alongside another mirror. Approaching this work made me feel simultaneously like a younger self obsessed with making diaries or best friend scrapbooks and like a worried parent about to rifle through my child’s bedroom. I found spending time with the sickly sweetness of these sticker-encrusted pages - evidence of a very internal process of anguish - uncomfortable. It felt intrusive, and perhaps this was entirely the point.

The room these works sit together in is bright, bathed in fluorescent light. There is an adjacent room that is darker and sheltered from this glare.

Carefully formed in the center of this dimly lit space is Rushdi Anwar’s The Circle of Knowing and Unknowing (2012-16). Divided into two distinct halves, Anwar’s circle on the gallery floor is made up of sticks of white chalk on the one side, standing slightly taller than the layer of velvet-like black pigment on the other. Nearby, a video piece derived from this arrangement is projected onto the wall, a shaky close-up orbit around the piece shot from floor level. The fall of past civilisations comes to mind. Demise brought about unwittingly and fashioned by their own hands, perhaps, or the apocalyptic impact of one society taking over another.

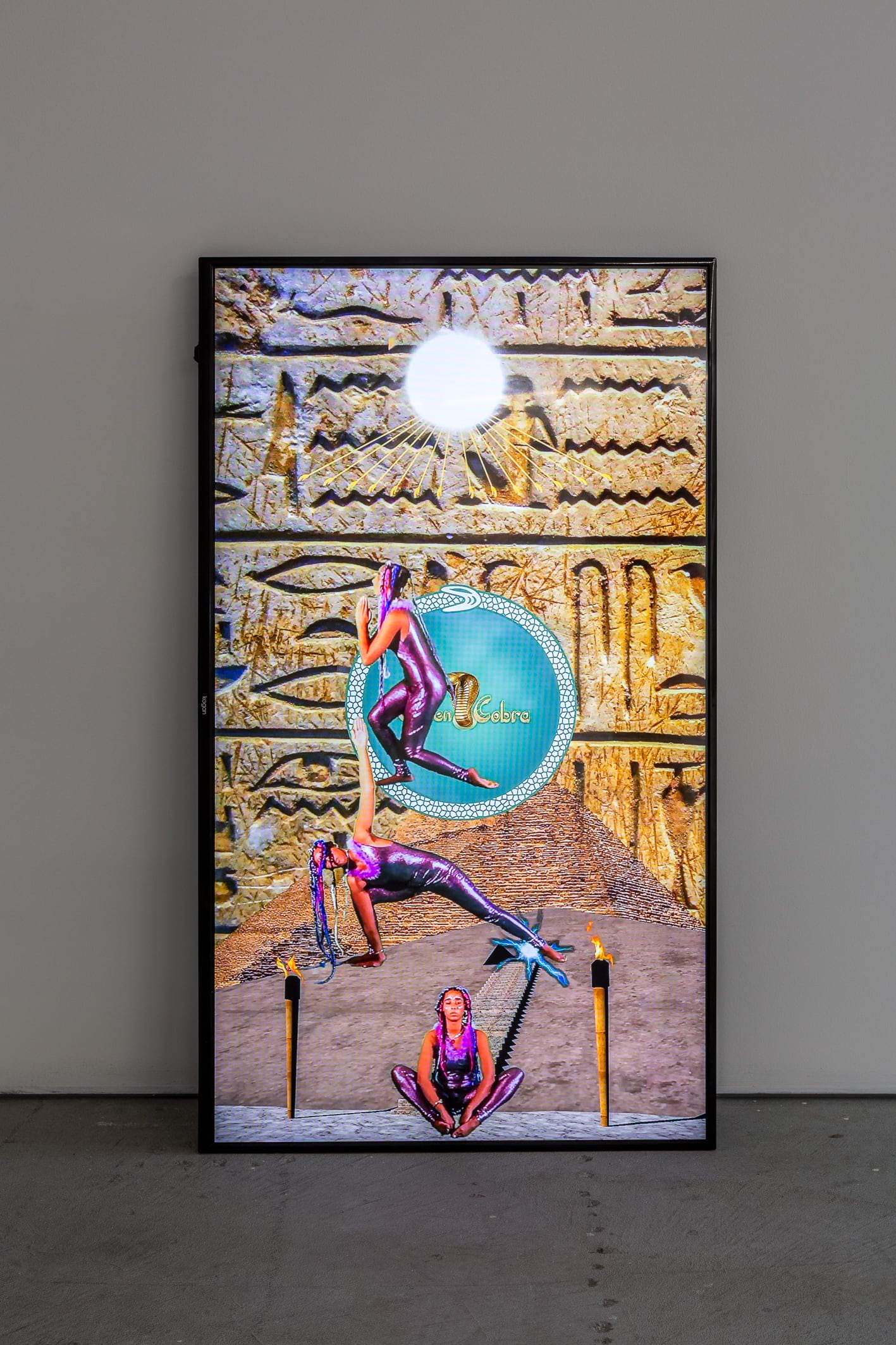

Leaning against the wall in the same room is Tabita Rezaire’s video work Peaceful Warrior (2015). This digital collage acts as a portal to a parallel universe grounded in the teachings of Kimetic yoga and paradigm of qtipoc self love, as well as a guide to cultivating resilience in this realm. Through an evolving digital collage Rezarie, in a purple sparkle leotard, commands authority and leads the viewer through a transformative decolonizing practice from angry to peaceful warrior. We must breathe. We must eat well. We much imagine a world with out misogyny, homophobia and racism, in order to survive in this world where such things are the norm.

Featured across both spaces is Tony Albert’s photographic series Optimism (2008). The series is unified by a recurring figure in a series of different everyday settings. With their back to the viewer, it is as though they are leading us into each scene. Be it at the football, school or a trip to the local swimming pool, the figure - Albert’s cousin - always carries the same woven bag on their forehead – a Jawun.2 Through the open weaving pattern of the Jawun we catch a glimpse of the items inside, packed according to the activity anticipated. Despite the title, this work is not about optimism alone. Our countries are still occupied, still designed to suit European ecologies, still dominated by logics that dismiss our knowledge and humanity. The Jawun embodies country and ancestral knowledge. Its presence in places that could be considered as white public space troubles the mythologies that give power to the colonizing population. Carrying it in these spaces is in itself an act of defiance and a demonstration of resilience. Through this we can visualize people living well on country in the past, present and future.

As Gertrude Contemporary settles into their new premises it seems pertinent to state the obvious. This is a contemporary art space that sits on the unceded territory of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation. This is acknowledged in the exhibition materials, however I couldn’t help but wonder if it might have been fitting to include an artist who identifies as Wurundjeri in this exhibition. I say this not to discredit Georgie’s curatorial approach but simply because it is worth putting forward, and it leads to another idea.

Renni Eddo-Lodge’s recently-published book Why I Am No Longer Talking to White People About Race tackles the issue of structural racism. In it she states that there is a difference between being included and working toward restructuring an exclusive system.3 Octopus 17: Forever Transformed exists as a symptom of an overwhelmingly unjust status quo, but together curator and artists have made a valuable contribution to the complexity of our times, stimulating further questions.

Where is our resilience from? And who are we resilient for?

Katie West is a Yindjibarndi woman and artist living and working in Narrm, Melbourne.