Artists: Hans Baldung Grien, Monika Behrens and Rochelle Haley, Naomi Blacklock, Eric Bridgeman, Giovanni Bendetto Castiglione, Albrecht Dürer, Mikala Dwyer, Emily Hunt, Clare Milledge, Judith Wright

Witchcraft is in. From Lorde to YouTube sage-burning tutorials, Wicca and ritual have found a new home in contemporary culture, especially within online communities. Five decades ago, second-wave feminist theorists reframed the witch as a woman who simply did not fit the model of chaste femininity and was thus persecuted for her ineffable sexuality. Decolonial thinkers soon followed to reconsider the racial anxieties underpinning witch hunts and reframed Indigenous shamanism as an alternative to Western paradigms of enlightenment and rationality. More recently, queer theory has also looked to paganism, citing witchcraft as a non-normative behavior and witches as figures who exist between a masculine and feminine identity. The witch is an outsider figure par excellence. It is no surprise then that the art world has turned to questions of modern sorcery.

The University of Queensland Art Museum’s first show of the year, ‘Second Sight’, enters this increasingly-popular territory. With playful anachronism, the show grounds today’s neo-pagan expressions to four historical objects: a nineteenth-century witch’s globe and three early-modern prints. The globe is possibly the most intriguing object in the show. Positioned at the exhibition entry, it hangs above the viewer’s head and refracts light in all directions. These superstitious objects were typical of nineteenth-century households and promised to deflect the witch’s spell back onto her, both saving the home and cursing the witch. At the core of the exhibition, in a small dimly-lit room, are three prints by Albrecht Dürer, Hans Buldung Grien and Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione. Dürer’s and Grein’s witches are fabulously wretched, their faces pinched and mean, robes flying off and breasts sagging like icicles. By contrast, Castiglione’s witch is sultry; surrounded by magical props, she casts her spell with the limp wrist of a bored supermodel. These three prints form a strong centre to the show, offering a nucleus from which contemporary reverberations move outward.

Admittedly, some of these echoes are more successful than others. Emily Hunt’s prints and ceramics form the most direct link to the show’s historical material, yet lack the alluring presence of the citation itself. Similarly, Judith Wright’s three panels and artist book adopt the medieval motif of the ‘phallus tree’ and yet, again, the sexual perversion so intriguing in the original material becomes subdued and didactic. Mikala Dwyer’s wall drawing Spell for a Corner (2015) and sculpture Green Fairy Necklace for a Wall (2015) mimic domestic adornments (such as the witch’s globe) to explore the spiritual aspirations of modernism. Spell for a Corner in particular distills this odd relationship between spiritual healing and geometry. Dwyer cites the early-twentieth-century, Swiss-German artist Emma Kunz as an inspiration but one cannot help but think also of the Guggenheim's recent darling Hilma af Klint. While Dwyer draws from a surprising and neglected art history, here too the copy doesn’t quite live up to the original. Ultimately, these works simply demonstrate the difficulty of translating ritual into representation.

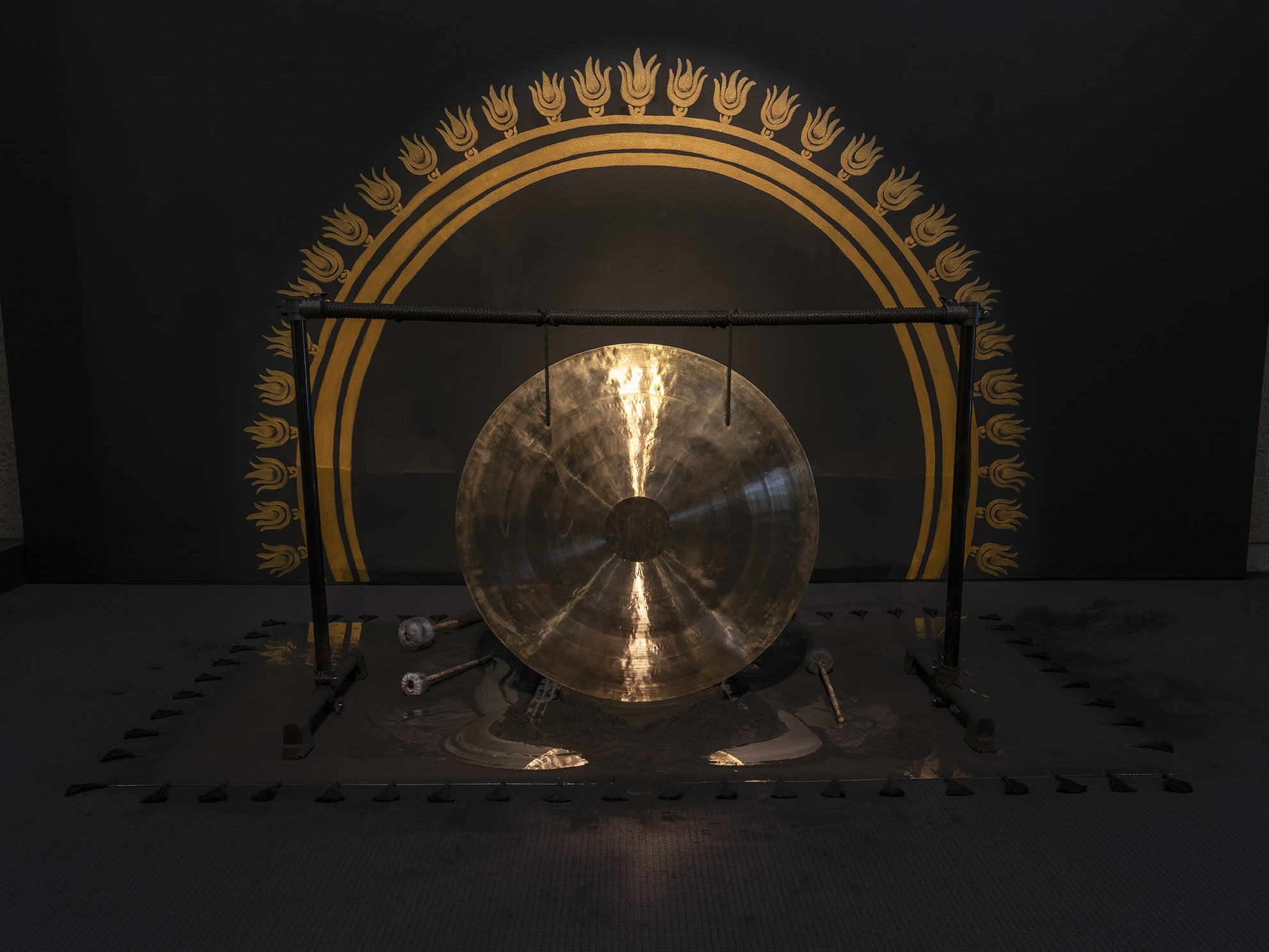

For this same reason, ‘Second Sight’ is strongest in its performance and sound works. A good example is the sound work Raven Tirad – F Minor - 128bpm (2019) by Austin Buckett and Tom Smith, which was incorporated in Clare Milledge’s installation Art as Fieldwork: Hot Spell on the Way (2019). Buckett and Smith took the F minor triad (a chord using the ‘Devil's interval', or tritone) as the starting point for the piece. In an uncanny conflation of the real and the recorded, the performance layered MIDI preset pipe organ loops with Buckett’s live playing of the organ. Although the triad may evoke feelings of unease and foreboding, it is in fact an incredibly standardised form: it can be repeated and built upon continually, almost like a preset in EDM. If the work sounds generically spooky, that’s because it is. Buckett and Smith adopt two forms of aural readymade—the tritone and the preset—to create a double-layered uncanniness in which sounds are familiar yet displaced. Naomi Blacklock’s performance, Aflame, A Singing Sun, takes a more earnest approach to magical traditions. Blacklock’s performance drew equivalences between the radiating light waves of the sun and the reverberation of her own body as she struck a large, metal gong. Sitting beneath a painted Prabhavali, the work invoked a non-European history of worship and adornment. Here, the artist’s performed paganism offers a way to acknowledge multiple histories and a springboard to more communal and visceral ways of being.

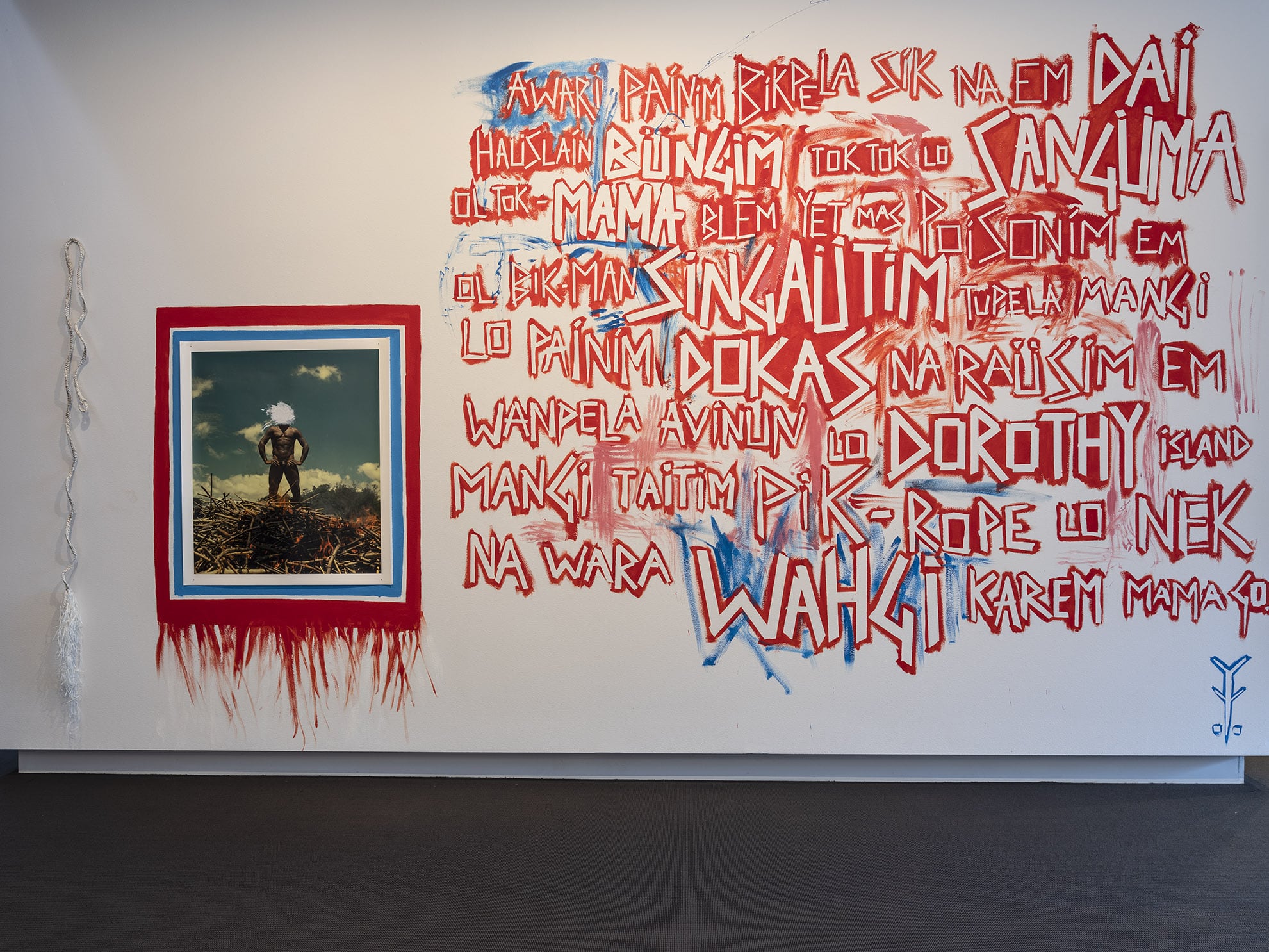

Eric Bridgeman’s large wall drawing similarly looks outside of western histories of witchcraft. Stenciled in manic red print is the story of a cursed flying fox, accompanied by the photograph of a proud-standing, naked man from Bridgeman’s extended family. The text translates to:

Awari (flying fox) became very sick and died.

The family met to discuss potential witchcraft

They said his own mother had poisoned him.

Some big men summoned two men,

To find Dokas and eliminate her.

One afternoon at Dorothy Island

The boys strangled her neck using pig-rope,

And the powerful Wuhgi River carried our mother away.

In these words, Bridgeman references a different cultural story—that of the Yuri Alaiku clan in Papua New Guinea—but also points to the violence incited by accusations of witchcraft. While the witch may provide the first world with a long-sought contrarian figure there are, of course, still many across the world who are persecuted and killed for being ‘witches’. Strangely, this element of Bridgeman’s work is not mentioned. The inclusion of the artist’s Kuman (shield) Paintings (2017-2019) and his collaborative project Karem Kai Kai (2019) seem to be a bit of an afterthought. These are interesting projects in their own right, reviving traditional shield-making while rethinking the violence associated with such objects. But the shields are really about brotherhood and protection, not sorcery as such.

The inclusion of Bridgeman’s shields speaks to a broader confusion within the show. While ‘Second Sight’ presents some interesting works and makes good use of its historical material, I couldn’t help but feel it lacked a certain criticality and cohesion. Ultimately, it’s hard to know what the show really said about its subject. It seemed to propose magic and ritual as positive forces, and that the gallery may be a place to house them, but nothing much beyond this. The exhibition clearly showed that there are artists interested in witchcraft; what it failed to do is ask why.