Twenty First Century Naked Apes: Handaxes and the Genesis of the Mental World

I wake up and do my compulsive morning scroll: an activist friend’s picture of stolen land; a witty defeatist environmental meme; dazzling selfie after selfie with unrelated captions. One of them is mine. A new club night!

Fucking hell. It’s nearly 2020, I’m thirty-two with tonnes of social capital, a modest amount of intellectual respect and no ‘real’ capital. Apparently, inequality is increasing. To continue the global structure that maintains this trend is insanely dangerous, but it feels as inevitable as planned obsolescence. We are anxious, highly intelligent, lonely twenty-first century apes aware that our actions are destroying our habitat yet feeling powerless to stop it. In a ‘post-truth’ era, the scientific voice, stripped of its authority, has been drowned out. God is dead, the Market has prevailed.

The Market led me to University. I had uncritically accepted the prevailing tertiary education myth: select my passion at age eighteen, graduate in my twenties and then be paid for the work that my course trained me to do. But I lingered, jumping from degree to degree—I had vague doubts about the Ivory Tower, but ultimately I blamed my lack of willpower and focus. I discovered my like of evolutionary psychology and philosophy. I won some academic prizes. If you look deeper, I acquired this intense achievement orientation when I moved from Aotearoa to Australia—a child’s unconscious reaction, an attempt to replace the emotional amputation of losing my Māori culture. We were forced to move because of my mother’s postcolonial bipolar disorder. Situations power feelings, which power thought. Now, I can’t stop thinking about the merits and demerits of social media after being cancelled and uncancelled so many times.

Once, I tweeted about the smartphone, that it is similar in size to the bifacial handaxe. The handaxe, whose uses are varied and debated, was invented 2.6 million years ago and is the longest used tool in human history. As with our phones, the bifacial handaxe was on our person at all times. While many animals use tools, we are the only species who use tools to make other tools. It was from my charismatic professor, an Indiana Jones of psychology, that I learned this—I retained a lot that semester. And so we see, situations definitely power feelings, which power thought. To him, the emergence of the bifacial handaxe is concurrent with the development of the only uniquely human qualities discovered to date: the cognitive capacities for mental time travel and embedded thought. If tools are carried around in anticipation of their use, some level of foresight is implied. If one is capable of thinking about things not directly in front of them, then infinite thoughts and thoughts about thoughts are possible. The most successful tool invented by hominids and the earliest evidence of our interior mental world, the bifacial handaxe can be connected to the emergence of thought, representation, art, literature, language and a theory of mind. It is perhaps analogous, but it seems profound that the digital interface of our phone, as arguably the most prevalent and powerful tool today, immerses us into an entirely mental conceptual world.

Lonely In A World of My Own: The Great Turn Inward

I wake up and ignore the reminder on my phone from Insight Timer to ‘look deep within myself.’ It’s the spiritual version of the more popular Headspace app that guides ‘mindfulness.’ Current societal logic runs as follows: freedom is valued—you should be free, you are free to make choices and those choices are your responsibility so if you succeed you own it but if you fail it was your fault. I sought therapy and healing in psychologists, multiple, finding a new one when I felt I wasn’t gaining anything from our client-practitioner relationship anymore. Foucault’s able criticisms of ‘failing treatment’ crowd my conscious—my overall sense of feeling like a failure increases, and the will to live decreases.

It is the mid-1800s in the United States and William James, after disappointing his father by resisting medical training and ‘failing’ in his pursuit of art, survives his self-inflicted ‘sort yourself out or suicide’ pact by becoming the father of modern psychology. The link between personal responsibility and the field of psychology has existed from its very conception, with James crediting his taking responsibility for his life with his achievements thereafter. Did William James’ situation and emotions power his thought? One is tempted to draw on Nietzschean metaphor: an ad hominem makes us look to the soil and the seed as well as the plant from which the flower grows; you cannot separate the author from their work. This way, we attend to what is not being said or argued, the limitations of a position as well as its possibilities. ‘The Socratic virtues were preached because the Greeks had lost them.’1 In Nietzsche’s view, situational and emotional necessity, rather than an impassioned rationality, drove the history of ideas.

We see ourselves as independent and sentient, but psychologically co-terminus with our skin. Endowed with the special ability to take control of our lives via the decisions we make, we assume the self as centre. Thanks to the Enlightenment, we benefit from the scientific revolution—we have an unwavering belief in reason and our supreme rational ability to be the masters of our own destiny, in responding to and anticipating circumstances in the overall pursuit of some goal.

These cognitive activities have trended into an ‘Ideas Culture,’ a ‘Hyper-Enlightenment.’

With TED talks, podcasts, panels, ideas festivals, tweets, we are obsessed, searching for the next Big Idea that will ‘save us.’ As we tether ourselves to our phones, we are pulled further into our heads and out of our bodies and surroundings. The prevalence of therapies like mindfulness that explicitly direct us to move away from our thoughts suggest that we have become lost in our own minds and that we are more anxious than ever.

The tendency in Western methods of thought is to see the individual as autonomous. We live in a symbolic world of reason, language and ideas, finding full expression in the non- space of social media discourse facilitated by our smartphones. This space attempts to represent and interpret but is not reflective of our concrete, immediate, direct and embodied reality. One is not better than the other, but there is excessive Cartesian emphasis on the mind as the centre of human experience. But, with fake news and Cambridge Analytica, our digital, thought-based and emotional worlds are liable to manipulation by nefarious interests. The Enlightenment has lead to an Anti-Enlightenment, as well as a Hyper-Enlightenment—two sides of the same cognitive coin.

Orwellian Irony of Power: It’s not your fault you’re not dancing (even though it feels that way)

I am a DJ, a utilitarian entertainer. I read social groups for a living and therein lies why myself and many other DJs are addicted to social media. At club nights, I am an artist with a passion for enriching the clubgoer’s spirit. In my more commercial jobs, I am tasked with grasping the cultural vibe of groups in order to musically serve the dancing majority. I make character judgements based on my observations—there is the person with the eyebrow piercing whose haircut says something about their half-ironic take on pop-emo culture and their friend with the face tatt who wears Acne sneakers. So, I play both hard techno and The Veronicas. I know that the artist from Marine Serre has the cultural and sexual power to keep at least one third of the pretentious crowd there, so I’ll keep them dancing. I validate her by flirting with my eyes, making them think I am enjoying watching them dance. Therein lies the explanation for why the club stays full until 5am and, as the closing DJ, I earn another hour of work. Another individual announces a politically impressive ‘something’ about ‘popularity.’ Now, there is a DJ who just played a locally prestigious festival—everyone is turning to them for social approval cues on whether it’s okay to be entertained. I change tack a little and become a bit classier musically to suit. My musical decisions operate as a power source to the space—I manipulate mood, thought and actions through the manifestations of my perceptions of this social nexus. This is the aim of DJ’ing in its most cynical and crudest form: keep everyone dancing, drinking, consuming. I instinctively understand that we are not isolated individuals; rather we are embodied points through which power flows in social space-time.

We strive for autonomy but the architecture of our being is that we are not responsible for all we do. There is ‘rational appraisal’ and ‘truth,’ but what drives us into action is social influence, whether we are aware of it or not. Situations of power will power feelings that power thought. Even as I write this article, I feel stupid, impotent and moralistic proposing an alternative thesis of the self, as if to say that simply understanding is enough. Sure, ignoramuses contribute to states of affairs, but most things only happen because the powerful want them to happen. I would go so far as to suppose that the central thesis of this piece is actually less likely to be considered plausible by those to whom it is intended to help (the regular person) than it is to those in power to whom the whole power structure horizon in society is actually visible.

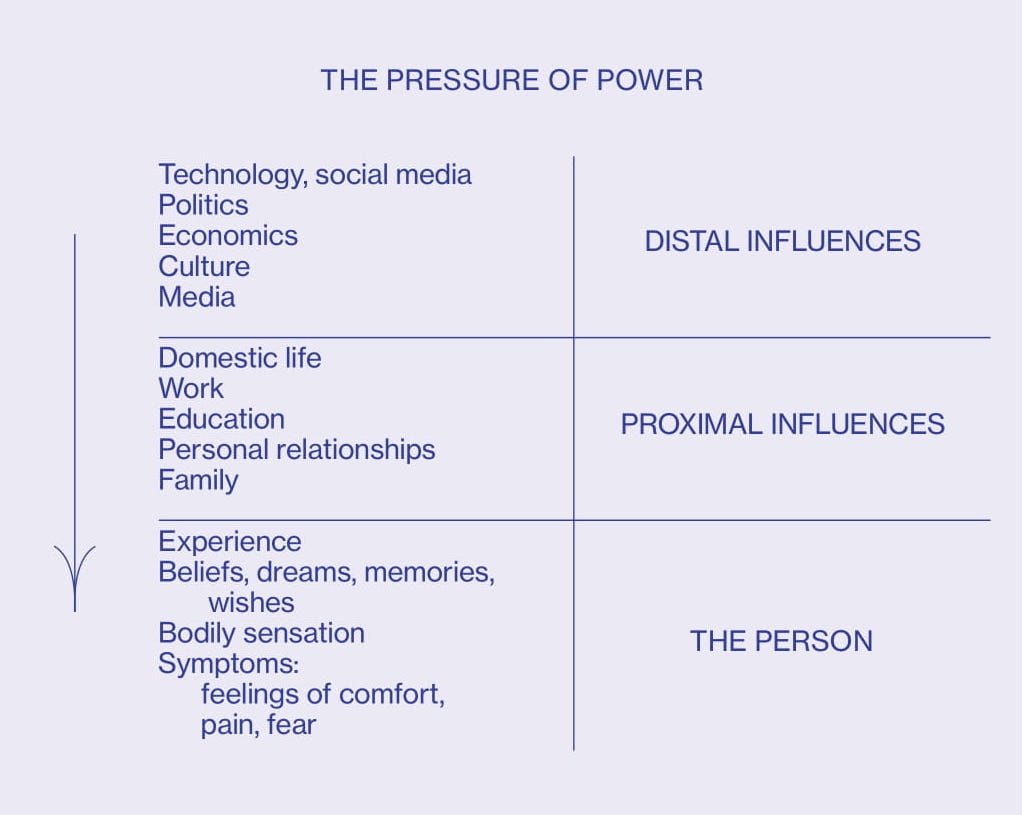

We generate our power both from within ourselves, and through strong distal influences such as social media, economics, culture and other powerful individuals. These powers affect the person and, through them, other proximal institutions, like relationships and education. Being further away, distal powers are strongest but often more hidden to the individual. A more proximal influence is less powerful, but due to its immediacy to the individual feels like it is more powerful. For example, as might be the case with a student, a University ‘makes a decision’ in the sense of spontaneously exercising free will over us; it is far more likely to be the case that the University’s ‘decision’ is conditioned by economic events which operate at such a distance from us that we cannot even discern their basic properties. Or, closer to home, in underground and artistic circles it is sometimes said that people from Sydney are more open to strangers, less cliquey and less likely to engage in cancel culture than people from Melbourne. Yet people are unlikely to attribute this behaviour to the high cost of living in Sydney (itself a result of wider economic and historical forces) forcing individuals to keep their networks open for support. Situations power thought.

Distress that we experience is attributable to the point in a system of power in which individuals find themselves. One’s ability to alter their position, influence people or influence events is limited by the availability of power within their social environment. No power is afforded to individuals outside of the social areas they occupy. Broad political, technological, cultural, media and economic global forces, rather than sources proximal to the individual, are the main sources of power (see below).

When people suffer psychologically, they become aware of how much they desire change. However, no amount of mental manoeuvring changes phenomenological experience— power within us is not enough to change our position in power, and powers affecting us greatly are a higher-order of culture over which we have no control. Therapy helps people more effectively when using the powers available to them, but research cites the young, educated and ‘successful’ as gaining the most from therapy. It is due to prevailing ideas of self-agency and interiority that we blame ourselves for our internal mental ‘failures’. Maybe it’s on the DJ that you’re not dancing—they’ve realised that focussing on uplifting you isn’t in their best interests.

Chimpanzee Border Wars: Tearing Your Friends’ Faces Off and Killing False Enemies

I have gap tooth. It was the result of extensive grinding of my teeth after a group of peers cancelled me. The length of my teeth shortened after being cancelled the second time. When I was a dental assistant, I remember a dentist saying that tooth grinding is a new phenomenon, a manifestation of collective stress. Following a ‘soft’ cancelling recently, anxiety replaced my depression. I realised I’d rather be stressed than nihilistic; stress is to care and to care is to love.

And then we have the puzzling ‘intra’ cancellation within oppressed groups, often referred to as lateral violence. Frantz Fanon provided a superb analysis of this in Africa, whereby the pressure of French colonialists as a distal power bred discord and destructive dynamics within the oppressed groups themselves. Lateral violence’s outcome is the legitimisation of the oppressor’s unfavourable attitudes towards the oppressed. The result: our personal failings are blamed instead of the world’s injustices. This mechanism underlies what has become known as ‘political correctness,’ serving only to further entrench our own subjugation. I am no Liberal Democrat, but I believe that it is neither ‘political’ nor ‘correct’. As I write this, I anticipate being cancelled for the third time, and wonder whether I can AfterPay the dental damage.

As evolutionary psychology demonstrates, human beings arbitrarily differentiate themselves from each other in any way that affords them greater power when resources are scarce, even using a feature like skin colour. I spent my teens with racists and sexists in rural Queensland, in an area with the highest percentage of One Nation voters in the country. When I was thirteen, First Nations athlete Cathy Freeman won the gold medal in her historic 400m race at the Sydney 2000 Olympics. A friend of my family’s said: ‘that black bitch didn’t deserve to win the gold.’ My family is brown. This incident made more plausible my hypothesis that there are forces beyond our control determining our attitudes.

It is an intellectual error to attribute the causes of oppression to personal traits of those involved. As long as bigotry is viewed as an attitude, which the individual must locate internally and eliminate, we are unable to identify the causes of interpersonal conflict in the material operation of power. It makes little sense to attack the immediate proximal power, when we must treat the hidden and distal power-causes of an illness if we are to cure it.

In the same way that Fanon so deftly attributed the poverty and subsequent violence of the Algerians to the distal power of French colonisers, oppressed groups divide and quarrel, hindering solidarity against these strong distant powers.

It is here that the explanation for the ‘success’ of political correctness lies, despite material global inequality being at its peak and continuing to grow. It is no victory of liberalism but, rather, a turning inward to mental and linguistic factors, the digital interface and symbolic representations of domination. Inspired by a Derridean or Butlerian post-modern emphasis on language and discourse, the best of us become hooked on a verbal witch-hunt, searching and destroying non-existent linguistic and attitudinal demons within. The ‘real’ devil, usually tech-billionaires, laugh from a world outside of Twitter, looking to exploit those less wealthy. For the lower-paid masses, attention is redirected to our phones through addictive design and algorithms, exploiting our brains and spurring endless discord. Furthermore, our oppressors rebrand this as a solution and sell it back to us as online corporate activism. UberEats and ride-sharing services have become normalised and continue to keep our wealth potential distant.

We can all harbour evil attitudes or behaviours in the right conditions, but it is what constitutes these conditions that we must look to when there is desire for change. A pious online orgy of agonised self-purification and 140-character vilification of attitudes or intentions is inconsequential, but it is this way that at age thirty-two one could have tonnes of social capital, a moderate amount of intellectual respect and no ‘real’ capital. It is essential that we accurately view our internal, mental, psychological, symbolic, cognitive, linguistic experience in all its potentials, limitations and traps if we are to solve the problem of the twenty-first century ape.

Club as Alternative Education: Rescuing the Subjectivity of the Human Ape

One could argue irony in the synchronicity of importance between our interiority and our handheld devices — the bifacial hand axes millions of years ago and now, albeit with more control, with another, the smartphone. Our Enlightenment led to Anti-Enlightenment. We know that Facebook experiments and tampers with our feeds to control our moods. Everyone forgets that companies like Cambridge Analytica use Facebook data to engineer political unrest to hyperpolarise politics and swing elections towards conservative elites. Our subjective experience and political agency, once rich and unique, threaten to be transferable to Zuckerberg’s bank account.

Though we are embodied, our internal quirks and depths are given no space to exist meaningfully outside of the emotional and cognitive demands of consumer culture mediated by brute corporate force and affected by our smartphones. We are submerged in Zadie Smith’s ‘lazy river,’ unaware of how our Facebook Blue state came to fruition. The powerful withhold from us; we are unable to interpret our feelings or experience our full subjectivity, caving instead to orthodoxy and living a false consciousness while, materially, we are poorer than ever.

But, every now and then, techno so primal blasts your ears, bursting you forth with movement. Someone sticks their tongue down your throat. Disorienting but musically in-sync lasers beam across a sea of indiscriminate bodies. Your friend gives you a tab of acid, your ego dissolutes. We are not naïve in knowing that unhappiness will find other forms, but we know too that there is particular ‘outside-world’ unhappiness that sometimes dissipates when you enter the club. The modern meaning of the club is as private as it is public. Existence confirms itself positively in the excess of the club. That is why the club is often characterised by sensual extremes, because outside of it the ethics of survival are held in tandem with the ethics of moderation. By investing and imbuing in activities for a future subjects’ thinking, planning and existence, we do so only by consuming and destroying. The club carries out this negative movement to indicate clearly its independence in relationship to the thing: burgers at 4am, MDMA, vodka sodas, smoking rollies, broken toilet seats, time and money spent—spent for nothing. Spending establishes communication between existents, allowing a movement of recognition. Existence is confirmed in music, LMAOs, dance, eroticism and being high. It is in this that one seeks an exaltation of the moment and becomes complicit in acts considered debauched outside of club bounds.

The club is, at its best, a small public world, carefully crafted to accommodate, accept, love, exaggerate and give social recognition to subjectivity, a body. Homo sapiens have infinite shameful and embarrassing desires, regressions, kinks, devastating fears and forms of expression that are barely acknowledged within the exploitative emotional extremes and excessively cognitive frameworks of techno-capitalism. Historically it was (and is) the bravest revolutionary minorities, trans people of colour, who split from the mainstream, taking fierce agency over their bodies and subjectivities, that defined clubbing. No wonder! Dancing spontaneously within a malleable party is an authentic answer to an embodied understanding. We have the opportunity to live as ourselves in harmony with others, our togetherness a tactical affirmation of the fucked nature of our thrownness in the world. But pure affirmation of the subjective present cannot be maintained. As quickly as we detach from the thinking world, the drugs wear off, the crush goes home, the joy becomes exhausted and one finds oneself with nothing but the Uber app open. One can never possess the present.

Universities, psychologists, religions, governments and the market all invoke a normative paternalistic framework. They attempt to teach us ‘how to be’ based on an ideal. The beauty of a good club is that, albeit briefly, it nurtures an unconditional maternal love, allowing space for us to simply ‘be’ in the concrete, material, inequitable world.

Kōtare (fka DJ Sezzo) is a proud Ngāpuhi woman, DJ, writer and curator. She is interested in the concept of freedom, modern Māori and the magic of the club. In 2018 she created the experimental art club night, Precog. She has played at venues in Australia and overseas.