Gallery: Connors Connors

Exhibition: Then Sharply Turns

13 April - 13 May

Then Sharply Turns is one syllable short of the final line of a haiku; the prose subtly suggestive of something that has come before. The title of the third iteration of Conners Conners' showcase of emerging Melbourne-based artists completes a dubious stanza — the two preceding exhibition titles of 2021 and 2022 being Sounds of Pacing and And Shuffling respectively. The exhibition is curated by artist and academic Ry Haskings, co-director of Conners Conners alongside Vince Alessi and Narelle Desmond. The exhibition’s title came about after Narelle heard spectral-esque sounds in the Fitzroy Town Hall, Conners Conners' municipal home. There are reminders of Jacques Derrida’s Spectres de Marx (1993) and his notion of haunting altering our experience of being in time — a temporal disturbance where our bearings on the present are re-configured.1 This conglomerate of works present as an emblem of emergent artistic practice — a conceptual site hinging on notions of (in)visibility, presence and nostalgia.

The twelve artists featured in this show — all Monash and Melbourne University alumni — destabilise a sense of space and time across the two gallery spaces. Upon entering the first gallery, Yusi Zang’s curious painting of pastel blues and purples takes on the appearance of a Steiner veil, a painting technique used in Waldorf schools where layers of colour are superimposed to illustrate a being’s thinking, feeling, and conscious will. Barbed wire orifices disrupt a meditative impression, floating like jagged angel halo’s bound in intermediacy. Angelica Nervegna-Reed review of Zang’s 2022 TCB show described Zang’s work as turning “vulgar objects into a sublime state of existence.”2 Zang tells me that this painting depicts an open heart surgery procedure where wire plates are being fastened.

Besides their emergent disposition, the only prerequisites for the exhibiting artists were that their work be wall-hung, preferably new or not having been exhibited prior in Melbourne. Jasper Jordan-Lang’s Ouroboros sculpture has migrated from the stone ground of Canberra’s Mount Stromlo’s observatory to the gallery’s white plastered walls. Adjacent to Zang’s painting, Jordan-Lang’s portal-deadlock titled ISL-81-(15) - WORM is the only work that extends beyond its utility as a mundane object; adapted into some sort of sanctified futuristic device caught in the present. Its materiality of bronze and silver infers a fluidity between spaces and in-betweenness: one where a humble invertebrae meets a utilitarian post-millennial categorisation system.

Quietly positioned on the back wall is Angela Nolan's Silvertop. Characteristic of Nolan’s work, part of the photographic image is obscured during the image transfer process. Like Jordan-Lang, there is an ethnographic materiality to the diluted snapshot, perhaps from the gold rush or an animal being held captive. The photographic residue weaves a subtle balance between interrogating colonial symbolism and disrupting the fissures of memory and information transmission that occurs from image-saturation. There is reprieve gazing at the muslin stretched around a slightly larger wooden frame nestled above the former image. This wall construction is perhaps some sort of occupation — a reclamation of space, as well as history.

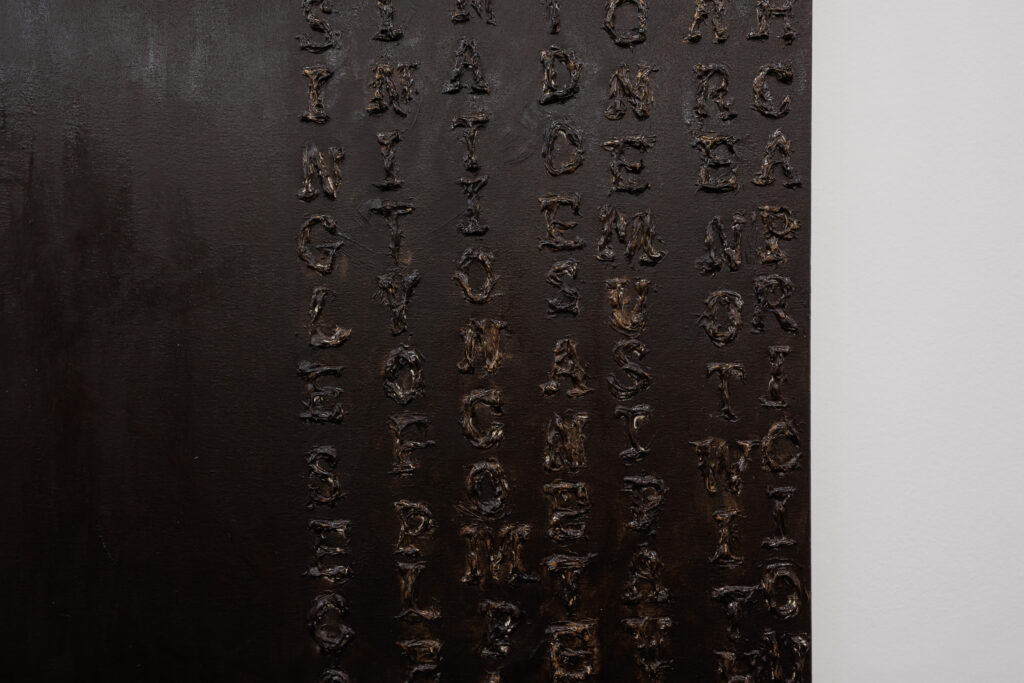

Bronte Stolz’s horrors of solidity continues the dialectical entwinement between ambiguity and ethnography in the second gallery space. Made of soap, Stolz’s wall sculpture protrudes from the left and asserts a solid presence. Daily rituals of washing come to mind, as well as questions about consumption, luxury and environmental degradation. This bulbous form also appears like a pseudo-relic; traces of soap have been found in clay vessels dating back to 2300 B.C, attributed to the Ancient Babylonians. On the opposite wall hangs Lei Lei Kung’s tactile Untitled (The Bad Glazier, Stu Watson translation). In reference to Charles Baudelaire, excerpts from the poem are carefully clumped across the canvas surface with modelling clay. His famed line ‘make life beautiful’ is repeated in sinistrodextral, whilst sentences such as ‘infinity of pleasure’ are contained in a Chinese calligraphy formation, coalesced with the muddy background. Here, the subject is transcribed in a material conjunction with the grotesque. A sense of the geographic is also encased: a textual neolithic settlement requiring patient transcription. It is clear that the artworks are collectively laden with aesthetic threads of history and nostalgia, matter and subject, spirit and objectivity.

Left of Stolz’s amorphous form hangs Melissa Nguyen’s oil painting Spirited, Striking, Successful, Stylish, Sexy, Strong and Seven. There are clear links with Nolan’s interest in the translated copy as Nguyen too is distinctly known for her use of pre-existing imagery, typically from her own adolescent archive. Two eerily distorted barbie-esque figures are set against a background of two more realistically depicted youth. The faces of the barbie-escue women bring to mind beauty filters on social media and their quantitative link to a rise in Body Dysmorphic Disorder. On the opposite wall is Kari Lee McInneny-McRae’s two toey, this is not a love poem: a wall assemblage comprising an elegant drawing strewn with personal text and wasabi peas positioned carefully on its surface. A wasabi coated handle-like structure is mounted to the left of the drawing, with a bronze tongue appendage attached complete with the title inscribed. Occupying an intermediate space between memory, longing and the present, like Stolz’s soap, wasabi’s antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties also invoke processes of purification and cleansing.

Loudly in the back left hand-corner is Britt d’Argaville’s wall sculpture, The pleasure is mine, a cluster of wrapped gifts mounted onto polystyrene. Shocking me into a recollection of familial childhood sentiment, the title makes inferences to service economies, value exchange, emotional anticipation and labour. The social phenomenon of gift exchange springs the question of French anthropologist Michael’s Mauss's, "What force is there in the thing given which compels the recipient to make a return?". Tommaso Nervegna-Reed's Untitled hangs on the adjacent wall. Scans of DVD spines stacked in the appearance of mangled venetian blinds carry almost didactic subheadings, in the tone of semi-analytical self-help VHS catch-phrases from a pre-internet library collection. With titles including ‘Personality Disorders,’ ‘Fascism: The Legacy of Hate’ and ‘Divorce,’ a clear interrogation of subconscious transmission of intellectual scaffolding and meaning is being constructed by the artist.

On the far opposite wall, Tarquin Charlesworth’s tectonic Channel (Stay Alive), a quasi-disco floor with diffused flashing fluorescent lights echoes eighties dance-floor hits (Saturday Night Fever, Staying Alive etc.). The audio is stilted, filling the room with a sense of disjunction of era and time. Charlesworth’s work activates the situational content of the gallery as the hall was historically used for debutones and balls. This soundtrack infuses Chris Madden’s adjacent Hysteric Realism I, II & III with both humour and nostalgia. A triplet of wall sculptures appear as diaristic contents of personal luggage, each containing worm-like hemispheres of digital prints as well as an assortment of discarded papers (a hospital visitor pass, a people and culture sign). The photographic material appears like a mish-mash of home-made internet paraphernalia, including an image of socks that circulated virally on tumblr and galactic-esque images of orbs. The tight encasement of the images as half-globes is evocative of the internet’s infinite sphere of reproduction, as well as the compartmentalisation of a sort of spiritualism.

All twelve works are approximately the same size, excluding Jemi Gale’s large-scale collaborative work, A Cure For Loneliness, which hangs in the first gallery room. Speaking with Gale, this work is part of an ongoing project to cure loneliness. Friends were invited to contribute to the work which is now an unstretched canvas flushed with bright colours and stylised motifs (a small butterfly flutters, presumably by Matilda Davis). The work summons group art therapy activities where participants are invited to engage in joint art making as an exercise of understanding and establishing boundaries, whilst reinforcing a sentiment of community — one that is inherently reverberated throughout the exhibitions curatorial sensibility. Against the back-drop of Victorian ornamentation, there is a present dialect between colonialism, materialism, mass culture and the in(visible). By the artifice of nostalgia, these dialectical entwinements bind the twelve image-objects together; in a ubiquitous tangling of the past, present and future.

Emily Kostos is an artist and musician based in Naarm/Melbourne.

un Projects’ Editor-in-Residence Program is supported by the City of Yarra, Creative Victoria and City of Melbourne

Editor: Carmen Sibha-Keiso