Teik-Kim Pok: I saw this one-liner on the internet — ‘My friend told me she wouldn’t eat beef tongue because it came from a cow’s mouth. So I gave her an egg.’

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded it was hard to keep up with all the stories of food, both good and bad, that shaped the way we experienced and are still experiencing this crisis. From stories of mutual aid via community fridges and gardens and the experience of empty supermarket shelves as supplies of tinned tomatoes and dried pasta were snatched up to the images of agricultural workers on strike throughout India, the politics of food was firmly in focus. Globally, we witnessed aggressive landgrabs by agricultural mega companies — Bill Gates is now reported to own more than 242,000 acres of farmland across the US1 and monitoring initiative Land Matrix has been reporting on what they are calling a ‘global land rush’, with new land deals being struck across Africa each month.2 This took place against continued calls for sovereignty and First Nations custodianship: in Victoria the campaign by community leader Arika Waalu Onus, Wuurn of Kanak LandBack, aims to raise money to buy back land for Indigenous self-sovereignty and healing.3 All of this was happening as many of us, stuck at home, never too far from our kitchens and under enforced conditions of lockdown, turned to daily rituals of baking, growing, sharing recipes and food stories as an outlet for creative practice.

Oishorjyo: Currently in India, the relationship (between economy and guts) feels very direct —entirely money based — with the rising inflation, reducing farmer’s rights on their own land, the State seems to have a direct control on our metabolisms.

Recently, a dear friend Meenakshi Thirukode (School of Instituting Otherwise) and I ran a workshop for disorganising, an open conversation hosted by Liquid Architecture, Bus Projects and West Space to explore the way artists can share resources to collectively build an arts ecology that sustains us and our communities. We had been speaking to artists as part of Food Art Research Network4 about practices of care towards place through artist-led food and community projects. We asked each of our interlocutors: Can we disorganise our relationship to capitalism through our metabolisms? We were interested in whether, through community economies, artists and activists can claim spaces of autonomy from capitalist systems of food production. During these conversations each artist agreed that autonomy was part of the goal, but they also spoke about the deeper relationships of interdependence with communities and ecologies that support their practices, and shared their insights into how we each might attend to the economies that we encounter through our guts. The workshop that followed was called ‘Disorganising Metabolisms’ and artists from Australia, UK and India joined the session. Throughout the evening thoughts about metabolic relationships to place and economies were shared in the chat. They are woven through the first half of this text as floating, unresolved and undigested fragments, drawing attention to the registers of metabolic thinking. The second half turns to a discussion of the recent performative artwork by Keg de Souza, Not a Drop to Drink, which took place at Arts House earlier this year.

Lana Nguyen: Different economies move through me, the distances and places that the food comes from, but it often isn’t fed back post-digestion into an economy or relationship that I know much about.

Biologically speaking, metabolism is the process that links the insides of our bodies, breath, digestion, tongue to the world through food, action and flows of matter. For many scholars, metabolism is a metaphor for both our connection to, and disconnection from, nature. And it all comes back to food: starting in the 1800s, economists and agronomists were concerned about a rift between urban and rural ecologies. The Enclosures or ‘Inclosures’ Act of 1773 is the first of a series of acts that, over the course of the nineteenth century, led to the dispossession of the working poor in England from rural economies. These laws, along with advances in agricultural practices, steered landlords to seek higher profits from their property through technologies of improvement. They restricted the rights of commoners to access ‘waste’, wild or common land; people were forced, in large numbers, to migrate to take up work in cities, often for very low wages. This meant that larger urban populations were separated for the first time in history from the rural economies that were feeding them. The ‘night soils’, or waste from food that people were digesting in cities, were not returning to fertilise and compost the soils in rural ecologies.5

Clare Qualmann: I like the ontological troubling between food and not food around waste, what matter counts as food and how ‘not food’ is transformed into food.

Karl Marx drew on the work of German agricultural chemist Justus von Liebig, who used the term ‘metabolism’ to describe the exchanges of consumption and feedback that characterise biological systems. Observing the increasing divide between town and country — the ‘urbanisation of the countryside’ — Marx identified a fundamental disruption — which John Bellamy Foster later called a ‘rift’ — in the exchange of materials between these places. In other words, resources were being extracted without being replenished, and in order to enable these depleted soils to produce the increased quantities of food necessary for the growing urban population, fertilisers were extracted from ecologies further away again. John Bellamy Foster writes about the environmental imperialism within such rifts, focusing in his writing on the trade in which migrant labourers from China were taken to Peru and Chile to extract nitrates and guano (the compacted manure of sea birds and bats) from nearby islands, which was exported back to Britain and other places in the Global North. This of course degraded the ecologies in Chile and Peru and created an ecological debt that would never be paid.6

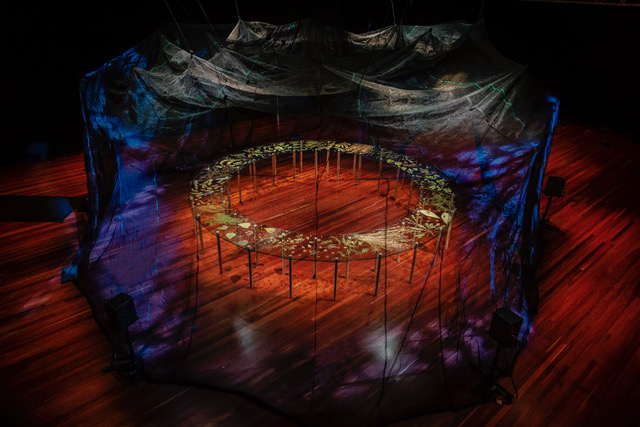

Keg de Souza, Not a Drop to Drink, 2021. Photos by Bryony Jackson

Keg de Souza, Not a Drop to Drink, 2021. Photos by Bryony Jackson

Zoe Scoglio: I’ve been becoming increasingly aware of how my gut is in a constant knot because of its participation in grotesque and necrotic capitalist/colonial systems.

Jason Moore in ‘Towards a Singular Metabolism’, which appears in Capitalism in the Web of Life (2015), writes that ‘[m]etabolism is a seductive metaphor’7, suggesting that the dualism between ‘nature’ and ‘society’ that the Marxist concept of metabolism traverses receives little critical interrogation. Exploring this dualism, Moore proposes that rather than an exchange between quasi-independent systems or objects, metabolism describes ‘all of the messy life making processes within the biosphere.’8 And as Moore writes, the framework of ‘nature’ on one hand and ‘society’ on the other was part of the changing symbolic order that would facilitate this ongoing dispossession of people from land and food cultures:

Not for nothing was this symbolic divorce of Nature and Society consolidated in early capitalism. The epistemic rift was an expression — and also, through new forms of symbolic praxis, an agent — of the world-shaking material divorce of the direct producers from the means of production.’9

While metabolism and the rift has sometimes been thought of as metaphor, it is one that is firmly based in the messy, disrupted and interdependent relationship between a body and its place. The point Moore is making is that in constructing the duality of ‘nature’ and ‘society’, scholarship over time has only served to harden abstractions inherent within each term. Metabolic thinking and practice might be attempting to heal, or at least recognise, such abstractions. Though we are just at the beginning of finding new epistemes that can encompass and discern what Moore and others call a metabolic shift, melting away the cartesian dualisms that are often repeated in Western language systems, as Moore puts it pithily: ‘Metabolism liberated from dualisms acts as a solvent.’10

Jacina Leong: Thinking here with economy, its meaning, to house/manage, and a management or attention towards what needs digesting, what needs nourishing: personally, socially, relationally.

It wasn’t until the 1990s that the human microbiome was more widely recognised as a site in which more-than-human organisms occupy our own bodies.11 This perspective has shifted the way we might conceive of and theorise our own subjectivities. Of late, metabolic thinking has become a site for calls for a new form of critical epistemology that takes embodiment, intuition, gut-based knowledges and internalised ecologies as a site of plural intellectualities.12 In Electric Brine (2021), a recently published book of short essays by the curatorial collective The World in Which we Occur, Margarida Mendes introduces the metabolic thinking that shapes their work: ‘Metabolic thinking is not a metaphor but a practical methodology that takes into account the scalar spaces, morphogenic processes, and political conundrums encircling materiality.’13 Metabolism, with its processes of inside and outside, nourishment and disease, might also be a way of imagining the visible and invisible in our own responsibility to and within the systems that support life. This practical methodology will necessarily take many shapes in response to the specific metabolisms that each body or even body of work encounters. So, this becomes a mode of attention, deep listening and observation, and it’s also one that requires a critical understanding of the scales of extraction that each life encounters. For instance, breath is part of our metabolic process — the more deeply we breathe the more quickly we can metabolise food, and our breath is dependent on many things including the trees and plants with which we share the earth.

Julia Bavyka: I think about insects doing cross pollinating work, weeds holding the carbon down in the soil, plants and animals.

Keg de Souza’s long-term research project Not a Drop to Drink asks complex questions in relation to future food systems, water scarcity and climate change, helping to show how artists are confronting the epistemic crisis within our metabolic thinking on stolen land. The project took place over five days at Arts House as part of Refuge, a six-year programme that asked artists and emergency workers to collaborate in thinking about the future. Not a Drop to Drink was developed in close cultural consultation with Senior Boon Wurrung Elder N’arweet Carolyn Briggs. N’arweet is an important knowledge holder on Boon Wurrung Country and has guided many cultural projects towards a more restorative vision for Naarm/Melbourne. The research, which is also supported by the Wominjeka Djeembana Lab at Monash University, saw de Souza hold conversations with fifteen experts including traditional knowledge holders, storytellers, ecologists and environmental scientists. She used this process to build collective knowledge about the kind of food that we might rely on in the near future as climactic changes and water scarcity issues take hold and ecological systems are no longer able to support the large-scale industrial agricultural practices that feed us. The printed also programme includes quotes from many of the interlocutors for the project. For example Zena Cumpston — a Barkandji woman and Research Fellow in Ecosystem and Forest Sciences at the University of Melbourne — gives guidance as to how we might eat in ways that are more attuned to the land that sustains us: ‘Eat food that is exactly right for that time, so that you are not ripping from Country, she is giving it to you.’14

As we enter the North Melbourne Town Hall it is dark and there is a soundscape of gentle water and soft voices. In the centre of the room a large structure of thin black gauze made of orchard shade cloth hangs over a table. The structure looks like a fishing net strung up in the shape of a crab pot. Within the net is a circular table made of glass and pressed within the layers of the tables surface are dried plants. Lights above cast shadows of the plants onto the wooden floor of the hall. De Souza greets everyone warmly at the entrance, an open flap that leads inside. The architecture conjures reverence, and while it reminds me of de Souza’s long practice of making temporary spaces in which discussions about race, knowledge, power and gentrification are held, this space feels more formal than earlier projects. The last time I was inside one of de Souza’s spaces was in May of 2015. It was a large gingham-patterned inflated dome in a hot gallery on the Lower East side of Manhattan in New York. We were talking about food histories of the island, mapping them on the floor while eating charcoal-coloured bagels.

The table accommodates about twenty people, maybe more, and is set with cutlery and paper napkins. We are directed to sit at the table and offered a choice between river mint and sage tea. I have river mint. I am sitting next to Jen Rae, an artist and food activist who has run the Fawkner Commons and Food Bowl for years and who has spent the last year running an emergency food supply for people impacted by scarcity during COVID-19. The circle stretches some metres across the room, and around the table several people are already seated — Wirlomin-Noongar author Claire G. Coleman, vegetable farmer Caitlin Molloy and Palestinian chef Aheda Amro. De Souza opens the dinner with an acknowledgment of country and words of solidarity to the people of Palestine — the date of the final performance and the date I attended, 15 May, falls on the anniversary of the Nakba, a very violent episode in the ongoing dispossession of Palestinian people and illegal occupation of their lands by the settler state of Israel. Next, de Souza introduces the project with a statement of protocol that asks audiences to respect that the work offers a space that foregrounds, listens to and respects the voices of marginalised peoples and that this ethic should frame any decision to speak and enter the discussion.

Over the course of the evening, we have a conversation while eating from a carefully designed menu of sustainable food. The ideas for the meal come from de Souza’s research and discussions with her collaborators. The meal has been realised in partnership with chef Nornie Bero who hails from Mabu Mabu and brings Torres Strait Islander cooking to kitchens across Australia. First up is the tea — river mint is a wild mint native to parts of the surrounding country. We eat mackerel, green ants and taro for the first course and later we talk about the growing interest in commercial insect production for protein. We eat a huge mushroom topped with saltbush, karkalla (native pigface) and prickly pear. We talk about the invasiveness of prickly pear (Opuntia Robusta) across Victoria and learn that it was originally planted as a very hostile form of fencing in the colonial division of territory and an attempt to foster a cochineal (a sessile parasite native to South America used to make red dye) industry. We eat pipis with damper, pickled samphire and daikon and talk about sustainable harvesting of saltwater creatures and the overabundance of carp in the waterways. (Claire G. Coleman says they are delicious and considered a delicacy in parts of Eastern Europe.) Lastly, we share baklava, a special treat made with love and brought to the performance by chef Aheda Amro. Earlier, she had introduced us to strategies for growing strong smelling sage, speaking about attuning to the weather and sharing her deep distress in the face of the destruction of her homelands.

In the circle, conversations are cyclical; they bounce, loop, go around. It is almost as though the words are caught in the fine net that surrounds us as they are digested and processed. Each of the guests brings specific knowledge of food with them, but the project also respects that we are all an archive of knowledge and a storehouse of food cultures. Guests share memories, concerns, threads of much larger thoughts and strands of research. The conversations move between scales — from the parasite that produces cochineal dye, to cows’ hooves eroding the banks of rivers, to the large-scale controls on dairy farming — each thread connecting the ways in which colonial occupation of territory and invasive industrialisation continue to enclose lands and displace connections to complex, place-sensitive food nature/cultures. The circle and the net suggest an architecture that, through de Souza’s careful hosting, invites voices to be woven across each other throughout the evening. This is a space in which to confront the complexity of choice and the future of food systems — particularly in Australia — while also learning to listen intimately to the intricacy of multiple perspectives. It is as though the circle is holding all of us, expanding our capacities for listening.

We face challenging food futures ahead. We are likely to be subject to increasing drought, plague, flood and supply chain disruption. The way we grow food here, from cattle farming to introduced trout in waterways, has been and continues to be extremely harmful for many ecosystems. It belongs to an industrial age that we, at the dinner, are in many ways trying to escape. Almost all the food produced and farmed in Australia is from introduced species, and these species do not always metabolise well with local ecologies. While these facts shape the discussion and haunt the conversation there isn’t any higher moral position that our speakers take, no one solution sought to the complex and deeply disrupted ecologies that are part of this colonial inheritance. By tuning into this broader metabolism, by talking about all these messy complexities while eating food, we might face these futures with a different relationship to place. The shape that relationship takes will depend on what each of us are called to notice, and how we take on the obligations of this metabolic attention.