Following the contours of my body

an archive

an assembly of history’s traces left in me.The impression is hazy

ill defined.

The act of tracing is precarious

...

Using what little is known

the tools at my disposal

a cloudy tongue

the fuzzy logic of Google’s algorithmGradually unearthing a picture

my ancestor’s movements across Moana Oceania.

I form my own interpretations, too.In tracing I see both layers.

I invent a world that does not exist,

until I make it appear before me

**

Returning Traces: Our ancestors left us clues (2020) is a new moving image work by Sione Tuívailala Monū, commissioned by Christchurch Art Gallery for their major new exhibition Te Wheke: Pathways Across Oceania. With work by over seventy artists from Aotearoa and the Moana Pacific, the exhibition includes tivaevae, weaving, carving, painting, video, photography and sculpture. Returning Traces expands on the theme of continuity and change in the Moana diaspora, and is the only newly commissioned work in the show.

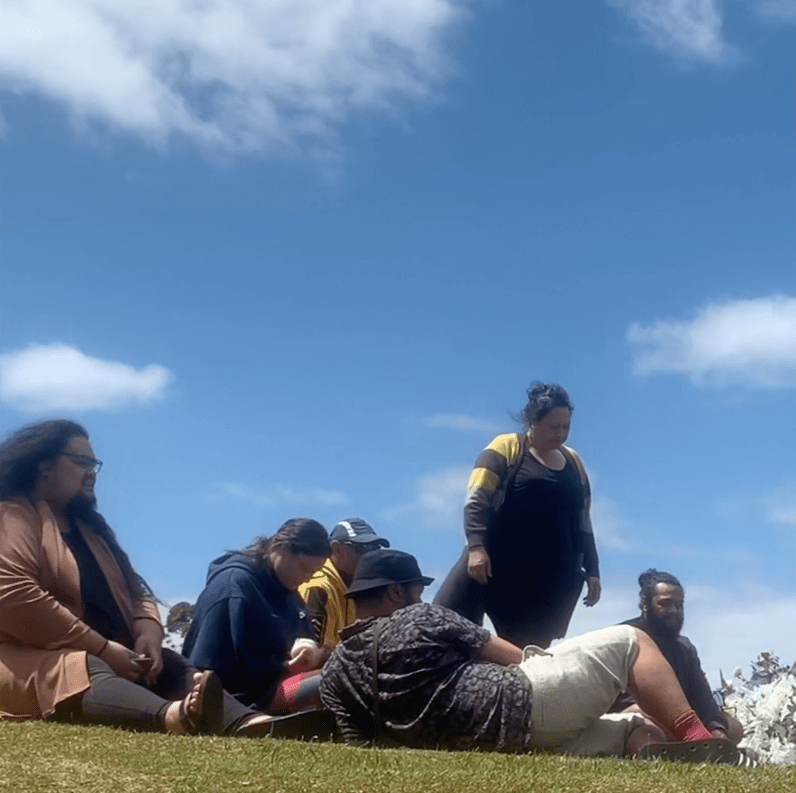

Filmed and edited entirely on their mobile phone, Returning Traces is an extension of Sione’s candid, video-based Instagram practice. As with much of Sione’s art practice to date, the figure is a major focus of Returning Traces. Throughout, Sione traverses different locations across Australia, Aotearoa and Tonga. As they cross borders, the landscapes and ecologies change significantly, however Sione remains a constant. Whether they’re waiting at a laundromat, messaging a Grindr hook-up, preparing food with family or sharing down-time with friends, Sione paints intimate scenes and invites us to share the vā tapu (sacred space) with them and the friends and family who reside there.

Sione is a multidisciplinary artist of Tongan heritage who identifies as fakaleitī.1 Like Sione, I have affiliations with multiple homes, one of which is Tonga though I was not born there. Like many others in the diaspora today, I search for pieces that reveal contours of my past.

Sione was born in Aotearoa and migrated to Australia as a child with their family. The nature of their father’s work as a church minister meant that their family moved often, settling in different cities across Australia’s southeast. While this experience was isolating at times, the dynamic of a large family of seven siblings helped. Sione recalls how supportive their parents Maumau and Matila were of their eclectic creative interests growing up.2 Their mother’s own practice of retaining anga faka-Tonga (Tongan culture) within her family was no small task. Born in Tonga, Matila migrated to Aotearoa as a child and grew up in Grey Lynn. It was there that her family household became a target by authorities during the Dawn Raids of the mid-1970s.3 The Dawn Raids signalled a point in New Zealand history where Pacific identity was pushed to the margins.4 Like many other Moana peoples in the diaspora, we find ourselves caught in the tensions of remembering in the face of circumstances that force us to forget, relinquish, move on.

The body and the mobile phone

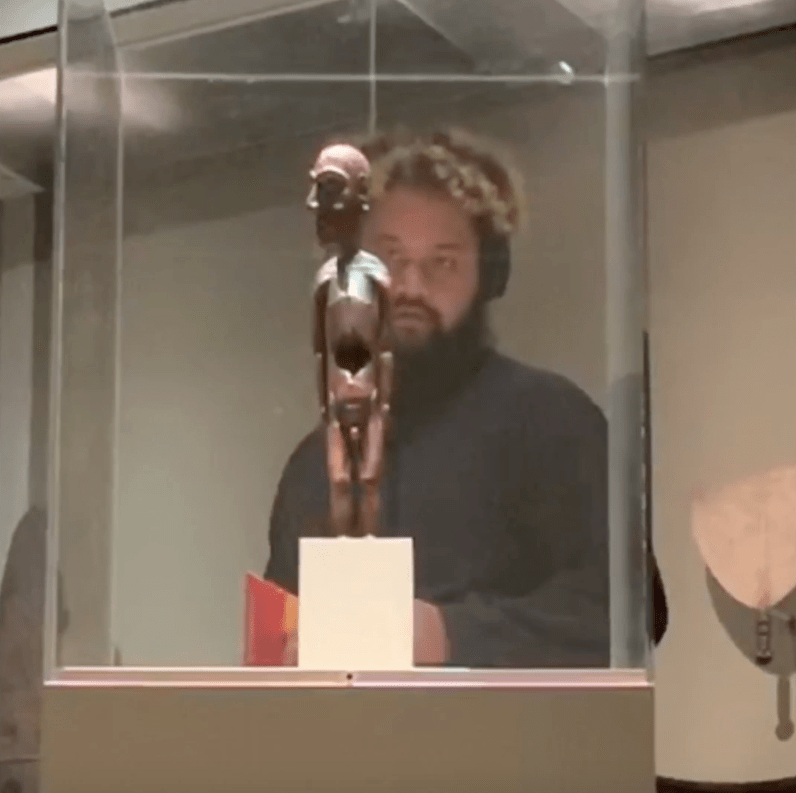

At the beginning of Returning Traces, Sione travels across their family’s hometown of Canberra on their way to the National Gallery of Australia. There in the museum they observe an ancestor, Moai Kavakava, an eighteenth/nineteenth century carved figure from Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Encased in a vitrine, Moai Kavakava is displayed alone and out of context for the purpose of preservation. While the vitrine walls are almost invisible, they still clearly intersect the space between Sione and their ancestor.

Sione’s video practice speaks to the way multiple histories are embodied within us. Bodies are often seen as a barrier, the first line marked in space that we are aware of. While skin is a sign of an exterior limit, bodies are surprisingly porous, and in fact extend into space well beyond the skin. Molecularly, we spread into the ‘outside world, mingling with it in ways that are not always apparent. We are entangled with the outside world, and this complicates binary demarcations of “inside” and “outside.”’5 Increasingly, mobile devices are thought of as an extension of the body. With theirs, Sione maps the rhizomatic patterns made all across Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa (the great ocean of Kiwa), and the various connections with multiple terrain they call home. Many points of entry and exit, like pores, like the body.

Indeed, Returning Traces is representative of the increasing use of mobile phones by those at the margins to document themselves; an embodied practice. Mobile phones enable greater visibility and access to one another and for this reason are an integral part of many marginalised communities. Through the use of inexpensive mobile devices and social-media apps, marginalised peoples are now able to document the stories that have been suppressed and ignored by heteronormative and colonial forces.6 In doing so, they reveal that their communities are not exotic nor a ‘problem’, as they have often been portrayed in the mainstream.7 Instead, they are remarkably ordinary — part of the fabric of this place.

Editing, ambiguity and the rhizome

Sione’s use of mobile technology is also reflected in the filmic technique used in Returning Traces, one that evokes the immediacy that the technology provides. The film’s scenes are stitched together with a disjointed editing technique that leaves its seams exposed. Narrative fragments are pieced together erratically, like a sequence of Instagram stories, disrupting the viewer’s attempt at finding a conventional narrative. Here, separate locations and time zones slip into one another, destabilising our sense of time and space — a play on time-space compression made possible by technologies.8

As a result, the film takes on the quality of memory; that circular field where different times coexist.9 Memory, like the body, is surprisingly porous. The exact details are ambiguous, always changing and adapting depending on the context. In her book The Ethics of Ambiguity (1947) Simone de Beauvoir argued: ‘Man must not attempt to dispel the ambiguity of his being but, on the contrary, accept the task of realising it.’ Similarly, Sione’s figure occupies an ambiguous space in the film. As in many of their other video works, the figure is enfolded in the present and portrayed somewhere between documentary and high drama. This is especially evident in the new work single bed/studio (2020), a series of short video clips that depict the artist in their bedroom-meets-studio during the COVID-19 lockdown. The work explores the intimacy of self-isolation while tapping into the ever-diminishing line between the labour we perform and the privacy of our homes. The emotional framing of crowded, extreme close-ups is juxtaposed with the bare objectivity of the camera’s gaze. Through this framing we see the present as a conflicted, ever-changing space that is constantly mediating the past and future.10

The ambiguity of an unfolding present can be likened to the rhizome, that stretching root system of plants, grasses and fungus. Deleuze and Guattari used the rhizome to theorise a system that allows for multiple non-hierarchical entry and exit points. They were suspicious of the singular concept of ‘history’ as a tree-like system or ‘grand narrative’, as described by Jean-François Lyotard. Instead, they argued that only transhistorical lines could lead us toward ‘becoming.’11

This calls to mind Hana Pera Aoake’s notion that the body is inherently political, made of multiple histories. Returning Traces’ editing exposes such lines, conveying a kind of intersectionality.12 Interestingly, historian and artist Kolokesa Māhina-Tuai explains how Tongan arts contain points of intersection or conflict, and it is at those points that artworks are at their most refined state, producing symmetry, harmony and beauty.13 Hūfanga ‘Okusitino Māhina also describes the Moana Ocean as a place of ‘connection, separation and intersection; of life and death, nourishment and malnourishment.’14 This view is very different to the colonial-European notion of the Pacific as passive or peaceful.

Such points of intersection are palpable in Sione’s nimamea’a tuikakala practice, such as their Kahoa Kakala series (2017-18) and their more recent floral masks. Nimamea’a tuikakala is the Tongan art of creating kupesi (geometric designs) with sweet-scented flowers to adorn necklaces, waist ornaments and dance costumes. So far, Sione’s masks have been exhibited in Queer Pavilion (2020), Moana Fresh, May Fair (2020) and Speaking Surfaces (2020).

And yet Sione’s practice is not wholly traditional.

Tongan art and Multiple Identities

The framework of Tongan art is divided into a number of categories. First are the three main categories of tufunga (material), faiva (performance) and nimamea’a (fine art).15 These are also classified in relation to the body, where tufunga and nimamea’a arts are ‘non-body-centred’ meaning the production of art is situated outside of the body and the body is simply utilised as an instrument. Then there are gender divisions, with tufunga and faiva predominantly male dominated and nimamea’a usually the domain of women. However, there are examples where these gender divisions overlap, such as women’s involvement in faiva as well as nimamea’a.^16

Sione’s art practice complicates a number of these divisions. Being detached from other Tongans in their youth allowed them to develop a unique approach to nimamea’a tuikakala.17 They grew up seeing an interpretation of kahoa being made by family members using plastic, grapes and beads, often learning by observing their creations in Facebook family photos and on Wikipedia. Sione recalls how they weren’t encouraged to make them because they were a boy. It wasn’t until a trip to Kanokupolu that they learned the traditional way of making kahoa for the first time. There they observed aunties and cousins working with natural materials such as flowers, bark and leaves in preparation for Fiefia Night. Today, they often use synthetic readymade materials in their kahoa, such as plastic flowers and beads which they source from Ōtahuhu and Māngere dollar stores. Inspiration for the shapes are drawn from everyday objects they encounter such as clouds, bananas or stars.

In Sione’s work, the cultural and community significance of these practices is expanded, letting in the possibility of multiple creators. Sione's online video performances also point to multiple identities in the process of creation. Like their floral masks, they invoke the notion of the mask as a means of transforming personal identity. Faiva is the Tongan category for performance arts such as song and dance, and literally means ‘to do time in space.’18 Faiva are ‘body-centred’, meaning the production of performance arts are made by the body; the body is the medium in the process of production.19 Online interactions using social media, such as those favoured by Sione, are intimately tied to the body in what Eva Illouz refers to as the ‘public performance of the private psychological self.’20

The idea of using social media to construct and play with multiple identities may not be what Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg envisioned when he remarked: ‘You have one identity. The days of you having a different image for your co-workers and for the other people you know are probably coming to an end pretty quickly ... Having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity.’21 Instead, Sione’s work celebrates the freedom that social networking sites, dating apps and other digital platforms bring.

If the linear or ‘grand narrative’ is a false construct, then disengaging from it can help us to create space for ourselves. In her book As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh (2012), Susan Sontag voiced her sense of discontinuity as a person: ‘My various selves - how do they all come together? And anxiety at moments of transition from one “role” to another.’22 This transition is felt as an infinitely hazardous leap.

Perhaps social media sites allow our multiple selves to become more integrated; a skin facilitating the flow of information between our inner and outside worlds. They are spaces for realising the self is not a fixed thing, but a dramatic effect that emerges from a performance. The need for such a space resonates with the question posed by Samoan/Persian artist, curator and academic Léuli Eshrāghi: What does wellbeing, what does pleasure mean for fa’afafine, fa’atama, queer, trans, non-binary peoples who have been violently removed from our earlier roles in intellectual and ceremonial life?

**

There’s a sense of growth as cyclical in Returning Traces, as symbolised by Sione’s nimamea’a tuikakala practice and mirrored in the floral arrangements adorning their family’s multiple grave sites. The cyclical nature of the natural world is also alluded to in the film’s references to Sione’s ancestral graves in Tonga and Australia. To film these scenes, Sione flew home to their village in Kanokupolu, Tongatapu. The film’s ending depicts Sione here, in a moment of contemplation at their family’s ancestral cemetery in Tongatapu.

Growth in Returning Traces is not tied to conventional ideas of proliferation. The film’s animated flora and fauna — a nod to Sione’s love of anime — suggests a new kind of life, but growth in the work is not depicted as inherently organic. Scenes with Sione and their friends are joyful and convey a sense of thriving, together.

Māhina-Tuai argues that in Tongan arts, one work of art cannot be more authentic than another. She explains: ‘Over time and space the three categories [of tufunga, nimamea’a and faiva] remain the same despite the incorporation of new materials, art practices and advances in technology.’23 The concept of ‘authenticity’ is an assumption that things are static and unchanging. However, in the Tongan tā-vā worldview, all things in reality stand in eternal relations of exchange, giving rise to conflict or order.24

Returning Traces, like much of Sione’s work, unearths multiple stories of place. In doing so, it reveals the interconnectedness of our borders, a line that stretches back to the time of our ancestors. While the continual reinvention of ourselves and our worlds makes them appear provisional, this does not necessarily make them fragile. Strength is also found in the network, our lives made of threads that are surprisingly resilient.

These threads criss-cross the Ocean as we continue to lay down our roots.