Exhibition: Ruu – Examination

Artist: Curtis Taylor

Gallery: Sweet Pea

‘Ruu is the Martu word for examination, mainly coming from the old Manyjilyjarra language’, explains Curtis Taylor. It means ‘to have a look, reveal something, or to sort of look at miscellaneous things’. It’s the day before the opening and Taylor has just unwrapped a large painting, Man on Fire (2019). A spirit figure in the background holds a jerry can, having presumably set alight the man immolating in the foreground. The mid-action nature of the scene and its shock-horror aesthetic give it a comic strip or film still feel. Taylor explains that he has a need to paint what is a commonly told story — ‘that you hear all the time’, about spiritual comeuppance. The collapse of different references and emotional registers is a pattern that continues across Ruu and within each of its works.

Explaining that the show is about a sense of gathering together things from his own home, Taylor says the works in the display ‘don’t have a relationship to each other, they’re separate.’ It is an insistence that invites the kind of close looking inscribed in the title. Artworks as household ephemera, randomly but affectionately deposited together. Like the rhythm of a busily filled house, we might pick up something, hold it and look closely, or let the gaze flit around, making odd connections.

Looking around the small gallery of works, some familiar from previous shows, some new, I’m struck by how I can’t quite place its logics — between the totalizing poetics of large institutional installations or the refinement of commercial gallery solo shows, there’s something both more visually frenetic and intimate going on here. Arguably the art world doesn’t create much space for articulating the visual complexity of artistic lives and roving interests. However, sweet pea is a unique kind of gallery, with the gentleness and experimental feel of an ARI; Taylor’s work is able to both run amok and make itself at home — ‘a plot of good seeds and gnarly weeds’ writes Lisa Stefanoff in the catalogue essay.

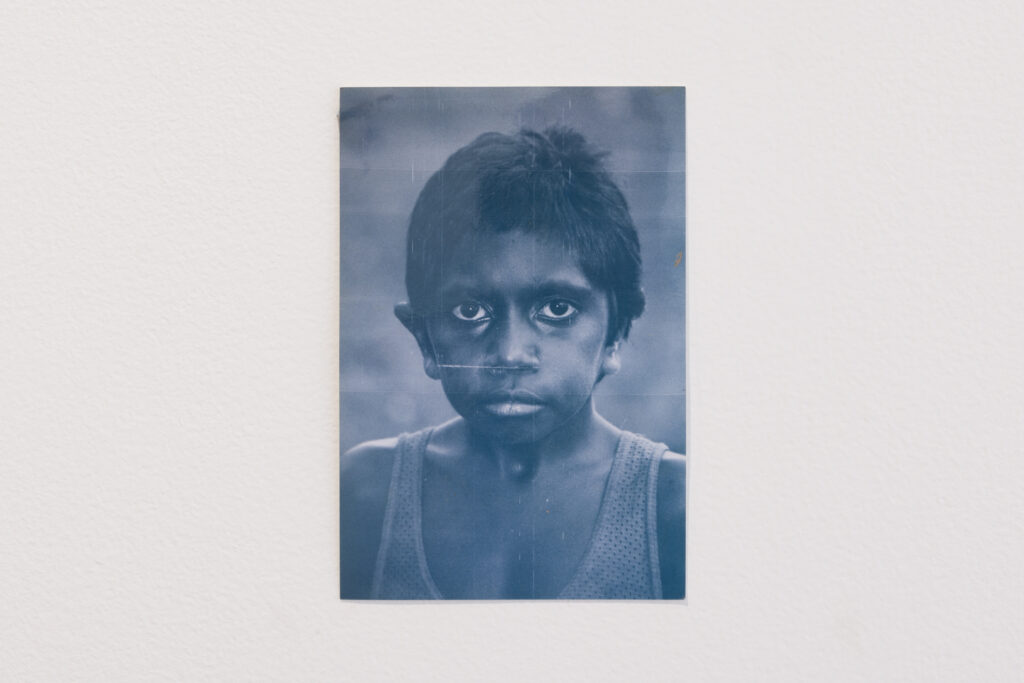

Ruu is curated from Taylor’s own archive — works that criss-cross times, histories, places and relationships — which is stabilised (but not disciplined) by the substrate of Taylor’s ever unfolding biography. The cover image for the show is a childhood photograph of Taylor in silvery blue tones that almost give it the historical aura of early collodion tintype photographs.1 It sets the tone of encounter for witnessing personal, community, and national narratives as echoes and re-told stories. We find the repeated inter-generational criminality of dispossessing Martu people in the paintings Richard Court and Charlie Court (2022), the collated reverberations of cultural continuities in a sculpture using rock art patterns burned onto a malu skin in Karlamilyi (2022), and a tribute to an enduring collaboration and friendship with Yolŋu artist Ishmael Marika in the sculptural installation of hanging speartree above rings of sands and ochres in Karu (2018). ‘A work that represents us’ says Taylor, while also saying there is no particular story to it.

In regard to a horizontal line of family and community photographs that follow Curtis’ portrait — mostly taken at Bidyadanga — Stefanoff asks us to ‘dwell in Curtis’ re-collection’. 'Dwell' is a fitting verb for the kind of thinking the exhibition encourages. It’s double meaning — to contemplate and to inhabit — has made dwelling a seductive concept in philosophy and art theory. I’m reminded of a line from Ivan Illich: that to dwell ‘meant to inhabit one’s own traces, to let daily life write the webs and knots of one’s biography into the landscape.' 2 Printed photographs baring the wear and tear of real use act as both a biographical tether and evince Taylor’s eye for the eerie, uncanny, funny, or affectionate detail. He points out small moments within the images — a little kid running over graveyards; a kid with a water gun between two priests at an Easter celebration; his dad in the midst of doing translation work which recalls memories of his travel all across the Kimberley and Pilbara.

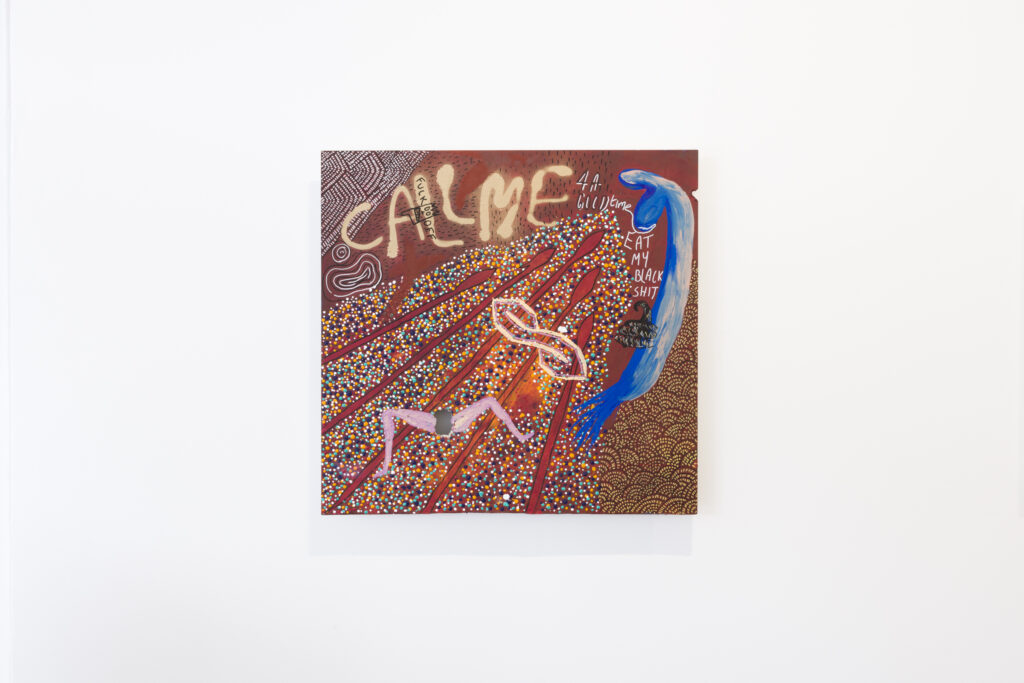

On the opposite wall there is Call Me (2022), painted on a piece of found discarded concrete that recreates the patina of a wall of a dilapidated house that’s been tagged and painted. One part of the image — of a woman’s legs around a hole chipped out of the wall — is something Curtis says he saw in real life. The work is laugh out loud funny, poignant as social commentary, and powerful as a recognition of the agency of reclaiming space through art. To dwell in these works is not simply to accept an invitation to contemplate them, but also to read them as acts of dwelling; the work of Taylor noticing the odd social knots of places and re-tracing them, then inviting us to recognize the artwork as another layer on top.

Another word that comes to mind is appropriation, both the art kind and the cultural kind. Taylor’s work is frequently not appropriate in the best ways, but when he borrows, references, uses, and takes, there’s always a compelling story underlying it. Curtis’ travelling relationships to people and places, such as homes across the Kimberly, Pilbara, and Perth, undergird his use of cultural materials, historical narratives, and pop culture references. Ilma (2019) is a recreated headdress of woven black, red, and yellow wool, reminiscent of those used north of Broome, with an upside-down aluminium Australian coat of arms placed in the centre, paying tribute to the 2002 action of Kevin Buzzacott, who reclaimed Arabunna kangaroo and emu totems by taking the coat of arms from Parliament House. Taylor’s work pairs two already reverberating cultural echoes that have local and national scales of gesture, symbolism, and cultural sovereignty.

Plethora of Wild Feral Cats (2022) references Dr. Seuss’ paintings of cats (which Seuss did largely for relaxation) implanting the ecologically minded illustrators works into the horror story of environmental havoc wrought by feral cats and their susceptibility to poisoning by 1080. It’s a work Taylor’s son helped to paint, and as Stefanoff describes it, he inscribes ‘his inheritance of activist stewardship of country and history’. The work provokes us to ask: what bedtime stories should we be telling? The kangaroo and emu forced to hold the very shield that represents and enables their on-going destruction, are giving some reprieve when the coat of arms is flipped. These stories aren’t pretty or easy, neat or polite, but they offer something more. They can be hilarious, shocking, joyous, beautiful, sustaining.

Taylor’s provocations and use of cultural forms are not always agreed with. ‘I’m telling the same stories that people paint in their own way’, says Taylor. But he continues: ‘If you’re there at the edge and you’re drowning and you can’t feel the bottom. That’s when you know you’re in the right place, to tell these kind of stories.’

Jessyca Hutchens is a Palyku woman, living and working in Boorloo. She is a curator and art historian, currently working as a Curator at the Berndt Museum at the University of Western Australia.