I am a descendent of the Butchulla people of K’gari. I’m a daughter of a Burmese man who left his birth country as a refugee at the age of five. My mother didn’t grow up on Country, she didn’t know she was Aboriginal until she was a teenager – my grandmother was worried she’d have her children taken away from her if the authorities found out. And so what knowledge I have of K’gari, and of Burma, two peripheries of the one Empire, I have gained mainly from books and art, rather than from conversations with family or kin. It is through ‘research’, then, – and its affiliated administrations, technologies, sources, protocols, controls – that I obtain the cultural- and self-knowledge which shapes my art.

Thus behind each of my paintings is a bibliography, a real series of ‘works consulted’ and in this way my paintings are themselves annotations on such bibliographies. But insofar as they function in this way my paintings also record the violent closure of different ways of knowing, and especially of the capacity for knowledge that arises from the multiple interchanges of direct presence. And so my art, even when I think it is at its most particularised or concrete, participates, if I can put it this way, in a merciless drive to abstraction, away from the aunties I never knew and the languages I do not speak, and towards the databases, the archives, and the search bar.

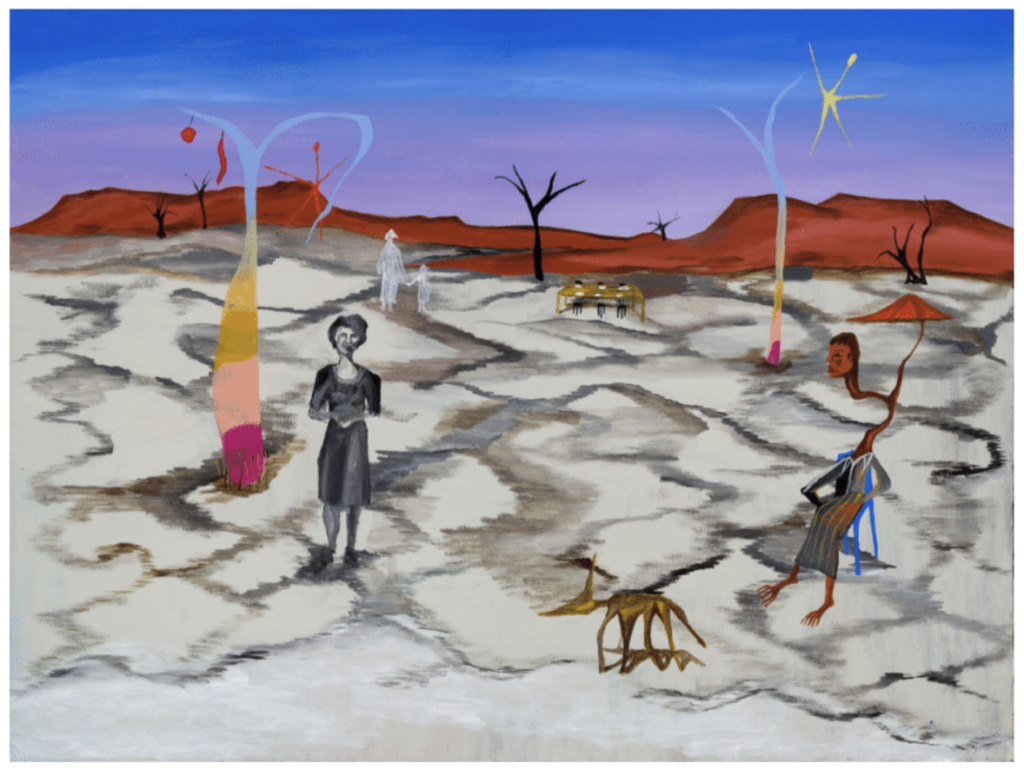

And yet. Sometimes, in the course of my researches, I give myself over to the seductions of nostalgia, in the sense which the cultural theorist and artist Svetlana Boym uses the word, that of ‘a longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed’. These moments – where I enter lost pasts in order imagine different presents – can issue in strange, estranged works. My painting The Nostalgia of Mother and Child is set on the beaches of K’gari. The landscape is populated by various real and imagined family members, all dead. At the top of the work float star-shaped spirits; recently these figurations have become more prominent on my canvases. After I had been painting them for a few weeks I began reading into Burmese folklore and discovered material on the traditional belief that when a soul leaves a body it is depicted asabutterflyfloatingabovethebody,calledleippya(လပိ ြ်ပာ).I’m not sure what to make of this. Maybe this painting is a concession to the epistemic forces which assail my work’s habitual structure of annotated bibliography.

Maybe it is a concession to other knowledges, from outside the patrolled domains of ‘research’, which try to pass through undetected, which are handed over in secret, betrayed, from one generation to the next. Or maybe it is only a fantasy projection. Maybe it is piece of unreason.

Mia Boe is a painter from Brisbane, with Butchulla and Burmese ancestry. Mia’s art practice records and recovers Indigenous histories, which Australia seeks to deny. This practice of recovery is urgent in contemporary Australia: the patient work of tracing historical trauma and violence can open new perspectives on the reasons for Aboriginal Australians’ present suffering.

Mia Boe, The Nostalgia of Mother and Child, 2021, acrylic on linen, 122 x 91 cm